A few weeks ago, we criticized a key part of Kamala Harris’s economic program in our post Why Price Controls Cannot Work. Now I’d like to criticize a key part of Donald Trump’s economic program: imposing a 10%-20% tariff on all imports, and a 60% tariff for all goods made in China.

This was the topic of Anne Bradley’s Religion & Liberty essay Toasters and Trade: How Misguided Policies Can Burn the American Dream from which we lifted her insights about vocation in yesterday’s post.

Her main purpose was to take issue with something vice-presidential candidate J. D. Vance said in a campaign speech: “We believe that a million cheap knockoff toasters aren’t worth the price of a single American manufacturing job. We believe in rebuilding American factories and rebuilding the American dream.”

Bradley, who is a Christian and a conservative and an economist, begins by unpacking insights from the pioneering free-market theorist Adam Smith, who showed the value of free trade in The Wealth of Nations. Among them are these:

First, we should never produce at home what we could purchase cheaper somewhere else. That would be imprudent. Second, “consumption is the sole end and purpose of production.” In a world of scarcity, we only use scarce resources to produce things people need and want. Production for its own sake is wasteful. This is a pro-consumer vision of the world. Rather than protecting producers, Smith saw that economic development hinged on directing scarce resources toward the needs of consumers, contra the prevailing theory of mercantilism, which Smith rejected as benefiting only a small segment of the public at the expense of everyone else.

In contrast, Vance, along with his fellow “post-liberals,” believe in mercantilism:

Vance believes that production is the end goal. If we make things here, we create jobs here, and that’s how Americans grow rich. It may sound good on the campaign stump, but this is why we must read and understand economics. We grow rich by making things at a relatively lower opportunity cost than others, which requires free trade.

Bradley explains, in depth, why Vance’s desire to use tariffs to keep out cheap toasters in an effort to build up American manufacturing jobs–which American presidents can impose without Congressional action– is wrong-headed. In doing so, she uses as an illustration the toaster industry. I urge you to read her analysis.

I would simply like to point out, in broader strokes, why tariffs, along with other protectionist economic policies, do not and cannot work:

(1) Tariffs raise prices. Trump has said that China will pay the tariffs, as if we are penalizing China while still allowing Americans to keep getting their cheap toasters. No, if the price of the toasters goes up 60%, importers will have to raise their prices 60%. The very purpose of tariffs is to raise prices. That way, American companies will be protected from competition. And without the downward price pressure of imports, the American companies can raise also their prices.

(2) Low prices benefit workers. America’s working class has a much higher standard of living than their counterparts in many other countries. This is because so many consumer goods that might be considered luxury goods in other economies are so inexpensive they are available even to Americans with lower incomes. If the goods sold in Walmart, many of which are “cheap imports,” were to go up 10%, 20%, or 60%, low-income Americans would be hurt.

(3) Tariffs hurt American exports. This is because countries that must pay tariffs for their products invariably retaliate by raising tariffs of their own. American companies may not make many toasters, but they do make products–ranging from wheat to high-tech machinery–that they need to sell to the vast markets overseas. Tit-for-tat tariffs that shut down our exports will devastate some of our most successful companies, resulting in huge job losses.

(4) Tariffs hurt the quality of American industry. It is never a good idea to shelter companies from competition, which not only brings down prices but also builds up quality.

Just as I am so old as to remember Nixon’s price controls, I can remember American automobiles in the 1960’s and 1970’s, back before free trade policies took hold in the Reagan era. Don’t get me wrong: those old cars looked great and are worth all of the nostalgia they evoke. But as automobiles, they were gas guzzling, inefficient, and backwards compared to what the European and Japanese automobile industry was turning out. When you bought a new American car–and it had to be American for most of us since the imports were tariffed out of most people’s price range–the “showroom tires” wore out in a few weeks and you almost never could approach 100,000 miles before you’d throw an engine rod or the transmission would go out. Japanese cars, on the other hand, could last well over 200,0000 miles, with much better fuel economy, performance, and fit-and-finish.

But once the trade barriers came down, American automobile companies had to compete with the Japanese and the Europeans, whereupon the quality of American cars improved drastically! Today’s American automobiles will easily go over 200,000 miles, and American automotive technology leads the world.

(5) Tariffs throw off American industrial capacity. If you order something that isn’t a book from Amazon, you will notice that it often comes with a notice that it is “made in China.” The same is true, again, if you shop at Walmart or an equivalent big box store. If we were to erect a great trade wall to shut China out of the American market–as the Great Wall of China tried to shut out the barbarians–do you think American industry could or would fill the void?

If American companies could make toasters profitably, they would already do so. The challenges of making and selling products in a greatly shrunken market –limited to Americans alone–would make it even harder.

America, it has been said, has a “post-industrial economy.” That is, it isn’t so dependent on manufacturing as it used to be. But we have a strong economy with, by global standards, a low unemployment rate. Our economy isn’t geared to making toasters, toys, and plastic utensils any more. It would take a long time to retool for American companies to fill the Walmart shelves, and even if they could, it would arguably be a step backwards for the American economy.

I do realize that trade has its tradeoffs. I hate to see the boarded up factories in our nation’s “rust belt.” And when a worker overseas makes in one day what an American worker would make per hour, of course a company will farm out its production overseas, putting American workers out of a job. That’s tragic. But the problems of those shut down factories go beyond what tariffs would protect them from.

Bradley says that American workers are five time more productive than their counterparts in low-wage countries. They can be put to better use, with the help of American technology, than making toasters. And their greater productivity can and should manifest itself in higher wages.

Under Donald Trump, the American economy and American workers thrived, not because of tariffs but because of reduced taxes and the removal of unnecessary stifling regulations. More can be done, but the answer isn’t to protect companies from competition, which helps the big corporations more than it helps their workers.

“We can avoid harming the working class by not manipulating trade and production patterns based on fallacies about how the economy works,” concludes Bradley. Rather, she says, “let’s support workers by increasing their opportunities, which means more market freedom—and more outsourced toasters.”

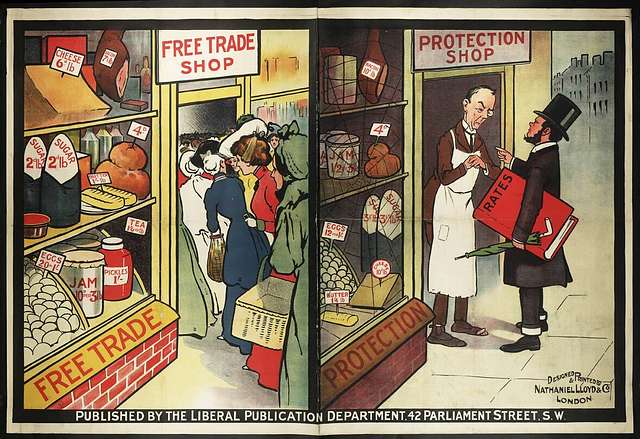

Illustration: UK political poster, 1906. “Liberal Party poster clearly displaying the differences between an economy based on Free Trade and Protectionism. The Free Trade shop is full to the brim of customers due to its low prices whilst the shop based upon Protectionism has suffered from high prices and a lack of custom.” Via Picryl, public domain.