Most conservative Christians are happy with the re-election of Donald Trump and the Republican’s big victory. After all, 80% of evangelicals and a surprising 58% of Catholics voted for him, even though his campaign pushed evangelicals to the sidelines and cast aside their most important issue, the pro-life cause. So what have conservative Christians gained from this election?

Here are some benefits that come to mind:

–Though there is little prospect of a nationwide abortion ban, the converse is also true: there is little prospect for a nationwide return of Roe v. Wade by statute that would override states that have pro-life laws, which Democrats had been campaigning on. States’ rights cut both ways.

–Democrats’ legal harassment of pro-life pregnancy centers should cease.

–Eliminating the conscience clause that allows medical professionals and Christian hospitals to opt out of performing abortions, as Kamala Harris had recommended, will not happen.

–Christian schools, adoption agencies, charities, and other institutions will likely be able to hold to their Biblical commitments without losing their funding or running afoul of government civil rights laws.

–Government support for mutilative surgeries and sterilizing hormone treatments in the name of transgenderism will decline.

–Tax laws and economic policies will benefit families.

–More conservative judges will be appointed. (What else?)

These are by no means insignificant, from a Christian point of view. The election is a major win for religious liberty. And yet, it will fall far short of establishing the Christian nation that the Christian nationalists, the Reformed and Pentecostal theocrats, and the Catholic integralists dream of.

In his victory speech, President-elect Trump said, “We’re going to fix everything about our country.” He resolved to usher in “the golden age of America.” Those are noble aspirations. We should hope and pray that this happens. And yet, do you think it will?

We have been blogging about the different kinds of conservatism and the various Christian approaches to politics and government. Just before the election, I came across two articles reminding me of yet another option: Christian Realism.

The conservative Methodist Mark Tooley wrote an article for the Christian Post entitled Christian conservatism and Christian realism vs. Christian nationalism. And Catholic author Joseph Bottum wrote an article for Religion & Liberty entitled Reinhold Niebuhr: The Ideal Christian Realist.

Bottum discusses in some detail the thought of the mainline Protestant neo-orthodox theologian who shot down the liberal post-war “social gospel,” insisting that human sinfulness made political utopias impossible, while still urging Christians to be politically engaged and to do what they can to promote justice. Bottum describes Niebuhr’s specific position this way:

There does exist a general definition of his Christian realism. It’s a political theory based on three Christian ideas: that we are basically sinful, that we are free because made in the image of God, and that we are called to love God and our neighbor. From the difficult combination of these truths comes an interest in the balance of power and a demand for humility in policy goals—along with a sense that pure realists have missed the genuine call to the good, and pure idealists have missed the genuine depravity of human beings.

Lutheran that I am, I can’t go all the way with Niebuhr. I believe that since we are “basically sinful,” that also puts our freedom in bondage. But we can have freedom in earthly, if not spiritual, affairs. And Christians do have freedom through the gospel. Bottum’s article goes on to explains how Niebuhr believed that while individuals are called to love their neighbors, this cannot be institutionalized collectively, so that the best that government can do is to work towards justice. Bottum also distinguishes between regular “realism,” which sets moral considerations aside in favor of sheer pragmatism, and “Christian realism,” which recognizes the limits of what we can achieve while still doing everything that we can.

Tooley contrasts Christian nationalism, with its “illiberal” opposition to democracy, constitutional rights, and individual liberty, with Christian conservatism, the traditional pro-American, limited-government variety. He makes use of the principle of “Christian realism” to argue for the latter, but I think the force of what he says can temper the expectations of conservatives as well. Neither a social gospel of the right, as Christian nationalists advocate, nor the assumption that free markets or a return to the Constitution can bring on a conservative utopia would be in line with Christian realism.

Here is how Tooley applies the concept:

Self-identified Christian nationalism contrasts with Christian Realism, which stresses the world’s fallen nature, warning against excessive idealism and perfectionism. Advocates of an established Christian state, whether Protestant Christian nationalists or Catholic integralists, aspire to a regime of the spiritually enlightened in which human sin is somehow minimized. In reactionary fashion, they romanticize a past Christendom that partnered church and state, and which no longer exists because of its failures. They assume that God’s sovereignty requires the state’s ratifying specific theological assertions. But the Deity does not need these assertions. And believers in religious freedom believe God is dishonored by allowing the civil state to define Him.

Christian Realism inclines towards religious freedom because it does not entrust Christian theological truth to state authority. The institutional church itself has enough difficulty safeguarding faithful articulation of the faith. Christian Realism understands that all civil societies are comprised of fallen humanity and characterized by competing interests, individual and social. Nobody is immune from self-interest. Even enlightened self-interest is plagued by human frailty and ignorance. Well-intentioned human exertions often have unintended and tragic consequences. Crusades for righteousness often wreak more havoc than the vices they targeted. There are never ideal situations in which one side embodies righteousness and perfectly defeats the opposition with the result of peace and justice for all.

For Christian Realism, there is no idealized past, nor is there an idealized future, short of the eschaton, completed by Christ’s return. Instead, in our fallen circumstances, we try follow God by seeking the greatest good possible in constrained situations, understanding that we ourselves lack absolute wisdom.

So how would Christian realism approach, say, the widespread acceptance and legalization of abortion? Not by giving up the pro-life cause. Moral truths are as real as any other fact. Christian realists should continue to work to protect the lives of the unborn in any way they can, including by legal and political means. But where abortion is nevertheless legal, Christian realists should focus on promoting the cause of life by saving one baby at a time, employing persuasion, counseling, evangelism, and helping women with “problem pregnancies.”

Another corollary of Christian realism would be accepting victories for one’s causes even when they come from flawed leaders. Back in the Moral Majority days, when conservative Christians first began their current political mobilization, the oft-stated priority was to elect Christians or at least politicians “of good moral character.” I still think moral character is important in a leader. But a Christian realist, understanding the universality of sin, might emphasize policies over the person. Thus, a Christian realist could rejoice in good conscience when the person advancing those policies prevails.

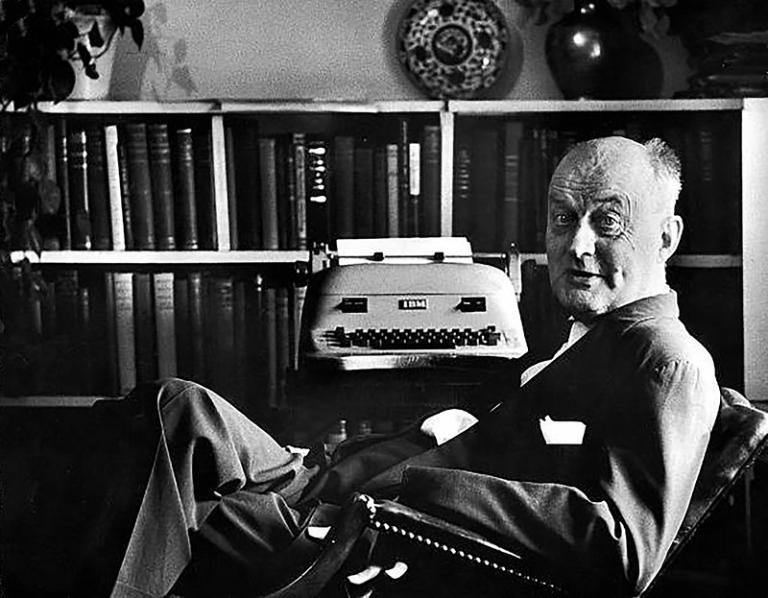

Photo: Reinhold Niebuhr in his office (1955) by Levan Ramishvili via Flickr, Public Domain