Scholars, ordinary folks, and even New Atheists have been discovering the profound influence that Christianity has had on Western civilization. Christianity has given us values (compassion, mercy, forgiveness), ideas (equality, freedom, human rights), and institutions (hospitals, universities, science) that just did not exist in classical paganism or cultures untouched by the church. (See Tom Holland’s Dominion and Alvin Schmidt’s How Christianity Changed the World.)

A new book shows how Christianity even invented what seems to be its nemesis today: the concept of the secular. That is, a realm that is distinct from the explicitly religious.

Classical scholar Nadya Williams reviews a book in Providence by intellectual historian David Lloyd Dusenbury entitled The Innocence of Pontius Pilate: How the Roman Trial of Jesus Shaped History. The book is about different theologians’ understandings of Pilate, but Dusenbury sees in that discourse the working out of the relationship between the spiritual and the earthly realms. Williams quotes him:

“The thesis of this book is that what we now call the ‘secular’ is not a Roman (pre-Christian) inheritance, or a late modern (post-Christian) innovation. On the contrary, the ‘secular’ is constituted by Christian philosopher-bishops, legal theorists, and polemicists… I am inclined to think that the term-concept of the ‘secular’ owes incalculably much (1) to a single utterance in the Roman trial of Jesus as it is narrated in the fourth gospel: ‘My kingdom is not of this world’ (John 18:36); and (2) to a singular interpretation of this utterance in the early fifth century by a formidable African bishop, Augustine of Hippo, in his Homilies on the Gospel of John.”

Williams delves into the origins of the word itself. “Secular” derives from the Latin saeculum, which originally meant the span of a human life, or what we call a “generation.” Later, it developed into the French word siècle, meaning “century.” Saeculum was a term for a measure of time, an “age.” It had nothing to do with a lack of religion. Indeed, the “Secular Games,” which the Romans held every 110 years to celebrate the transition from one era to another, were shot through with religious observances.

But then the word was used in the Latin translation of the Bible to render the Greek αἰῶν, or “age” (cf. the derivative eon). Williams explains:

In the Latin Vulgate, whenever Jesus refers to “this age,” the term used is saeculum. Likewise in the Vulgate, Paul uses saeculum to describe “this age” and its antipathy to Christ—e.g., in 1 Corinthians 2:6-8. The key to understand—and Dusenbury returns to this in his conclusion—is that in antiquity, again, there was no separation of religion and state, or sacred and secular (in the modern sense). But Jesus, with his brief statement about the nature of his kingdom at his trial before Pilate, made that very separation, between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of the saeculum.

I would add that there is also no separation of religion and culture in the other major world religions. Not in Islam. Not in Judaism. Not in Hinduism. Although some have tried to turn Christianity into another cultural religion, Christians come “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” (Revelation 7:9). And Christianity is for every age, every saeculum, because Christ is “far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named, not only in this age [saeculo] but also in the one to come” (Ephesians 1:21).

The original Greek in Jesus’s confession before Pilate uses the word κόσμοs (“cosmos”) or “world,” so that the English correctly renders the passage as “my kingdom is not of this world.” The Latin Vulgate also renders κόσμοs as mundus, “world,” but Augustine, in discussing the passage, interprets it in the sense of saeculum. For him, “this world” and “this age” constitute the non-spiritual realm, which often opposes the faith and offers temptations to lead us away from the faith. And yet this “secular” world is still part of God’s creation and exists under His sovereignty.

Some Christians, such as the monastics and Protestant anabaptists, would seek to separate themselves from this “secular” world, though the church would also establish orders of what were called “secular priests” who would serve parishes in the world.

I would add that Luther with his doctrine of the Two Kingdoms is especially helpful in sorting out both the distinctions and the relationships between the “temporal” and the “eternal” kingdoms. He also shows the value of what we would call the “secular” realm, explaining how God is present there too, though in a “hidden” way. His doctrine of vocation teaches that Christians are to love and serve their neighbors in their “secular” callings and relationships.

We might do well to bring back the element of time in the word “secular.” The age we are currently in may be oblivious to Christian truth, just as the ancient Greco-Roman age was actively hostile to it, but “the age to come,” in the sense of future generations or future time periods might be more open to Christianity.

Whereas Christianity can embrace both the spiritual and the secular, today’s secularism rejects the spiritual, assuming that this physical world is all that exists and that this present time is normative for all of history. Christianity is much more open-minded and offers a much larger and more comprehensive perspective.

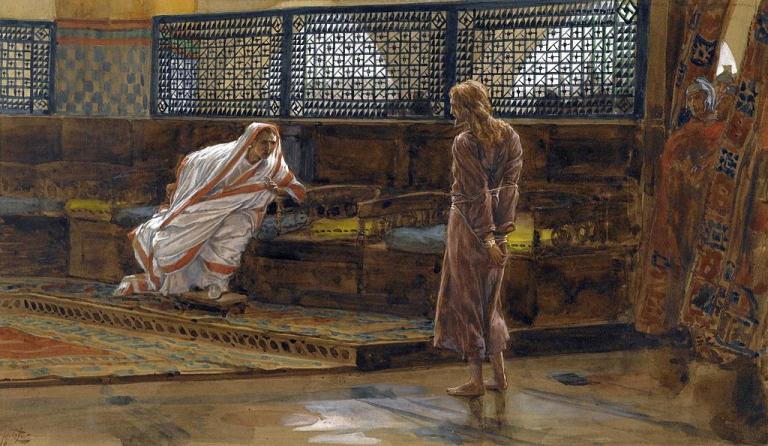

Illustration: Jesus Before Pilate, First Interview by James Tissot, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons