I grew up in a family of die-hard Democrats. They are still pretty much that way. At the time, shortly after FDR saved Oklahoma from the Dust Bowl, the whole state was fervently Democratic, though now ironically it is the one state in which every county voted for Trump. But back then I never even knew a Republican until I reached college age and my cousin married one, a mixed marriage we thought would never last. (But it did: the interloper was Cranach subscriber and sometimes commenter Bob Foote.)

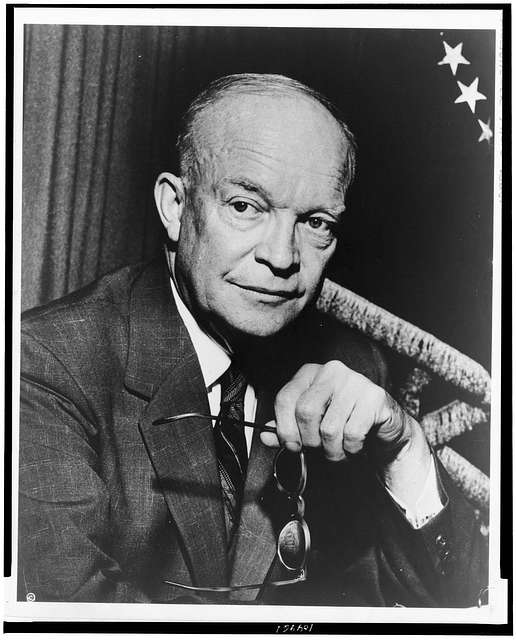

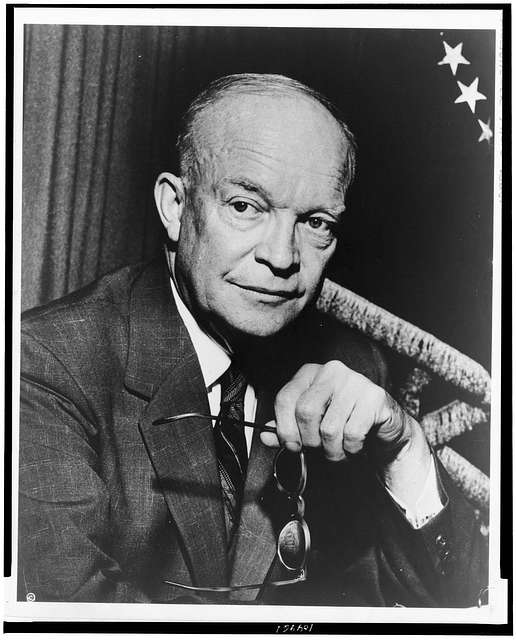

Anyway, in 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower ran for his second term. I was five years old. Somehow, I was captivated by the man, whom I saw on our black and white TV. I don’t remember how I acquired it, but I started wearing an “I Like Ike” button, to the consternation of my parents. I have to give them credit for respecting my civil liberties, even when I kept saying “I Like Ike” over and over again.

At one time, Eisenhower was considered a do-nothing president, but today his stock has risen to the point that historians now are ranking him in the top tier of American presidents, even in the top 10. No one can deny his accomplishments: as a general he whipped the Nazis; as president he stopped the Korean War; he built the international coalition against communism while opposing McCarthyism; he signed the first modern Civil Rights Act and sent in troops to integrate the Little Rock schools; he started NASA; he gave us the Interstate Highway system; he warned us against the “military-industrial complex”; and he balanced the budget. That’s a fairly decent record.

Eisenhower was a great administrator, as evident in his various careers in the military and the government. Administration is a lost art and greatly under appreciated today, but it is the key to getting things done and doing them effectively.

It turns out, Ike laid out some principles for the vocation of staff member. These were based on his own experience both as a staffer working his way up the unforgiving meritocracy of the military and as the man at the top of the hierarchy being served by his staff.

Think tanker Luke Strange has written about these principles in his National Review article One Thing New D.C. Staffers Must Understand about Their Jobs, with the deck, “The many who are about to get new jobs in Washington can thrive in their roles if they master ‘Policy Hill.’”

Strange is offering advice for the legion of new office-holders and their subordinates who will be taking positions on Capitol Hill. What Eisenhower says applies to government, politics, and the military, yes, but also to business, academia, non-profits, and religious organizations, including churches large enough for pastors to have a “staff.” It includes insights both for employees and bosses, explaining both what staffers need to do and what bosses needs to do in order to use their staffers effectively.

I’ll let Strange explain it:

Ike developed an ingenious concept called “Policy Hill” to give him and his staff the ability to prepare for, make, and implement effective decisions. On the uphill side, a staffer is responsible for developing, or “teeing up,” a decision for the principal. At the top sits the principal — the key decision-maker. Down the other side of Policy Hill lies implementation — all the things that the staffer needs to do with the boss’s decision to ensure that it is successful.

To start pushing an idea up the hill, the staffer needs to first be an “‘honest broker’ who can understand and explain the risks and benefits of any solution — both to the principal’s strategic goals and to his or her key relationships.” The staffer needs to determine the time-lines necessary for the idea to become a reality. “And a staffer should know whose buy-in the principal needs for each option, and in what order — and what way — they should be approached ahead of time.” After working through all of the options, the staffer knows more about them than anyone and should then be prepared to offer honest recommendations.

At the top of the hill is the “principal” who will make the decision and be accountable for it to the various constituencies. The staffer should support the principal’s decision with these groups, smoothing over disagreements and tamping down opposition.

Then comes the implementation of the decision, the downslope of “Policy Hill”:

Staff members must be vigilant that the departments and agencies are on board and doing what they are supposed to do. Along the way, a few tasks are paramount. First, measure success and trumpet impact. Second, deal with blowback — from the Hill, from frenemies in your coalition, from the media. Third, and most important: Do as much as you can to make the principal you work for look good either publicly or, oftentimes, simply within his or her party or department.

And thus the staffers will have loved and served their neighbors–their boss, their organization, the public–and fulfilled their vocation.

Photo: President Dwight D. Eisenhower by New York Times via Picryl, Public Domain