A number of conservative thinkers, in trying to address the political and cultural problems of our time, are blaming liberal democracy itself. They are maintaining that the combination of individualism, personal freedom, and free market capitalism, as cultivated by liberal democracy, undermine community, religion, and (ironically) the foundations of liberal democracy itself. But what these critics would put in the place of liberal democracy is not so clear. Might they take a turn towards authoritarianism?

John Ehrett worries that these conservatives are moving away from the traditional tenets of American conservatism–constitutional government, limited government, free enterprise economics, and civil liberty–to embrace, instead, a more authoritarian model. He specifically looks at the issue of religious liberty.

If the purpose of the state is to promote the common good, as these theorists say, how can that happen when there are different visions of the common good? That is, when there are different religious beliefs all being tolerated together?

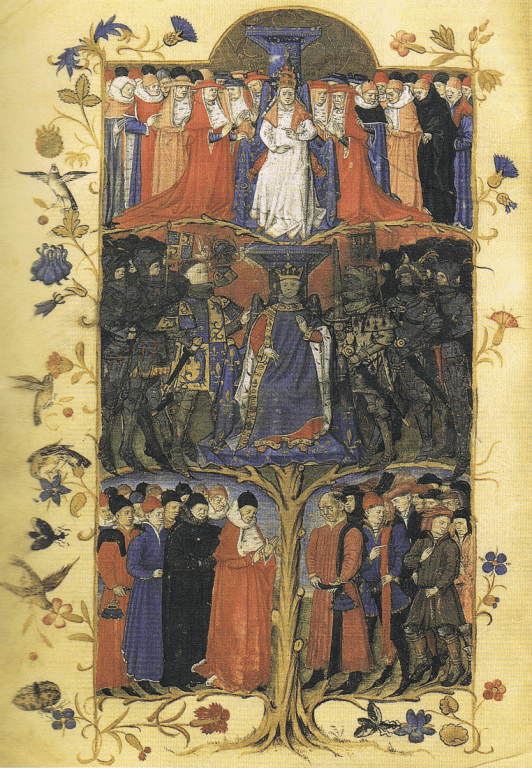

John predicts the rise of what he calls “Neo-Integralism.” Integralism is the Roman Catholic view that rejects any kind of separation between the church and the state. According to this view, the church is “integral” to the state, and the state is “integral” to the church. The political order must contribute to the spiritual ends as defined by the church. Thus we have the medieval notion of the temporal authority of the Pope over earthly governments. But we can also see a different type of Integralism in the Protestant state churches of post-Reformation Europe.

John expects that conservative theorists and Christian thinkers will put forward a version of Integralism, advocating limits to religious liberty and the other liberties that go along with it.

From John Ehrett, The Coming Neo-Integralism, in Between Two Kingdoms:

Speculation is always a dangerous game, but here is my controversial prediction: in the next 2-3 years, a not-insignificant number of conservative political theorists will gravitate toward support for an express synthesis of church and state, with all its ensuing consequences. I will call this ideology neo-integralism (most of its proponents wouldn’t use the prefix, but insofar as neo-integralism tries to resurrect a prior, premodern relationship between church and state, the additional descriptor makes sense). Neo-integralism, unlike what most Americans conceive of as “conservatism,” will willingly grasp the nettle of authoritarian politics, favoring state control of markets and close regulation of personal behavior. Most controversially, neo-integralism will ultimately dictate that political/spiritual leaders take an axe to the perceived taproot of liberalism: religious freedom. . . .

Why might this shift occur? Freedom of religion is, at bottom, the freedom to come to diverse conclusions about the ultimate destiny of reality—and, in a regime sanctioning the free exercise of religion, the freedom to act meaningfully on those conclusions. I would go so far as to suggest that a robust view of religious liberty necessarily restricts the power of any political leader to articulate a “thick” vision of the common good—a vision toward which all members of the community may be morally compelled to labor. A regime allowing space for divergent views of the eschaton (that is, the ultimate telos or purpose of humanity) to flourish is a regime that inherently circumscribes a political leader’s power to immanentize any eschaton at all: to what shared philosophical foundation can such a leader appeal?

To summarize all this: the new wave of conservative critiques of liberalism is largely predicated on liberalism’s perceived failure to preserve the “common good.” Divergent views of the Ultimate Good (that is, God), which are a necessary consequence of freedom of conscience, will necessarily thwart political leaders’ ability to organize citizens around a temporal “common good.” As a result, those who seek to elevate the concept of a “common good” over the subtler achievements of liberal democracy must ultimately stake out positions opposed to religious liberty itself.

As a Lutheran, I myself am comfortable with a degree of tension between the political and the transcendent—and I don’t find it especially difficult to make a theological case for freedom of religion. . . .

First, I have a question for those of you with a fuller knowledge of Lutheran theology than I do, humble layman and convert that I am: What was the theological justification for having a state church in light of the Lutheran doctrine of the Two Kingdoms? I know the historical reasons, but surely the Age of Lutheran Orthodoxy and subsequent theologians also had a theological rationale. It seems to me that the doctrine of the Two Kingdoms makes any kind of Integralism impossible. The Reformation definitely attacked the temporal authority of the pope and the church in general. I can’t see how a version that allowed the secular ruler to govern the church is much of an improvement.

Second, any attempt to integrate the church and the state, or make the church rule the state, or to figure out how a theocracy could work, or even to pose secular alternatives to our current liberal democracy can surely be nothing more than a theoretical construct. Does anyone really believe that in our highly secularized society the church can seize political power? Or become seamlessly integrated with a society that consists mostly of nonbelievers? Or make the general public obey God’s laws, when even believers cannot fully obey God’s laws, which is why Christianity is all about the Gospel? Can any church body that exercises temporal rule even be authentically Christian, given that it would inevitably be secularized at the expense of the message of the Cross?

Wouldn’t it be a better strategy for Christians to exercise their vocation as citizens–which does indeed entail political responsibilities–to develop more modest goals? Not to rule the country or solve all of society’s problems or usher in a new utopian Golden Age, but to adopt a far less ambitious Realpolitik and to pursue a few limited, though morally and spiritually-informed objectives?

Fight for the unborn and other life issues. Defend religious liberty. Protect the family. Isn’t this enough to keep Christian political activists busy?

Christian citizens should also be encouraged to promote their individual interests using the political process: Farmers, small business owners, workers in all vocations should agitate for their economic interests. Those concerned about the environment, the poor, peace, the national debt, educational reform, or whatever, should be encouraged to pursue those concerns. This will mean that Christians will not always agree with each other politically, but why should they?

In the meantime, knowing that this world is not their home, Christians would live out their lives according to their callings–loving and serving their neighbors, growing in their faith as they work through their trials, and doing the best they can–whereupon they will die and be received into God’s eternal Kingdom. There sin will have no dominion, and they will live forever in a reign of perfect justice and the ultimate community that they had yearned for on earth.

Illustration: The medieval hierarchy [with the Church and the Pope at the top; the King and earthly government next; and the common people below] by entworfen im Auftrag der Kirche – Europa und die Welt um 1500 (ISBN 3-464-64823-0), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7977851