What have you accomplished in the last 11 weeks? Luther took 11 weeks to translate the New Testament.

He was in hiding and in disguise at the Wartburg Castle, where Duke Frederick the Wise spirited him away after the Emperor declared him an outlaw who could be killed on sight after the Diet of Wurms. So presumably he had little else to do and few other distractions. But he made good use of his time.

Luther’s translation of the Bible from the original Biblical languages (for the first time since St. Jerome rendered the Hebrew and Greek into Latin) into German spread God’s Word far and wide. And it became the model for vernacular translations ever since

William Tyndale resolved to make a similar translation into English, and he went to Wittenberg and consulted with Luther on how to do that. Though Tyndale would be strangled and burned as a heretic (not by the Catholics but by the Anglicans, at the command of Henry VIII), his translation would lead to the King James translation, which preserves much of his phraseology, which, in turn, preserves an English version of much of Luther’s phraseology. (See this article by Graham Tomlin on both the similarities and the differences between Luther’s rendition and the KJV.)

Christianity Today has published an article by Ken Chitwood on Luther’s Bible, a new edition of which has become a best seller in Germany. In the course of an interesting discussion about the Bible in Germany, he quotes some tributes to Luther’s work:

“It is and will remain a classic. . . .Our understanding of the world and nature, our art, literature and music, our annual holidays have all been shaped by Luther’s Bible and the religious practice derived from it over the centuries.”

Christoph Rösel, General Secretary of the German Bible Society

“His great achievement was to infuse his Bible language with an extraordinary poetic power and beauty that later translations of the Bible have never equaled.”

Jochen Birkenmeier, director, Lutherhaus museum in Eisenach

Adds Chitwood, “The Lutherhaus curator points to the translation of the Christmas story in the Gospel of Luke as an example of Luther’s literary skill. He used catchy rhythms and some alliteration to ‘make the birth of Christ ring out and help to remember what is heard—like in a song,’ Birkenmeier said.”

Back in 1983, Christianity Today published another article on Luther’s Bible entitled The Bible Translation That Rocked the World, with the deck, “Luther’s Bible introduced mass media, unified a nation, and set the standard for future translations.”

Its author, Henry Zecher, calls Luther the “uncle” of the English Bible, Tyndale being the father. He sums up some of Luther’s influences on Tyndale, the KJV, and the other English translations taht would come later:

One strong point of Luther’s work that impressed Tyndale was the order given to the books of the New Testament. In previous Bibles, there had been no uniform arrangement; translators placed them in whatever order suited them.

Luther, however, ranked them by the yardstick of was treibt Christus – how Christ was taught: the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John); the Acts of the Apostles; the Epistles, in descending order of the Savior’s prominence in each; and, finally, the Revelation of John. Tyndale followed Luther’s lead, as have virtually all Bible translators since.

Many phrases we know today came from Luther, through Tyndale. From the German’s “naturlich,” Tyndale wrote “natural,” and the phrase “natural man” appeared in 1 Corinthians 2:14. Luther’s “auf dem gebirge” became “was a voice heard” in Matthew 2:18. Tyndale translated from Luther “the place of dead men’s skulls” in John 19:17, “Ye vex yourselves offa true meaning” in 2 Corinthians 6:12, “Doctors in the Scripture” in 1 Timothy 1:7, and “hosianna” in Matthew 21:15.

Like Luther, Tyndale eschewed the Latinized ecclesiastical terms in favor of those applicable to his readers: repent instead of do penance; congregation rather than church; Savior or elder in the place of priest; and love over charity for the Greek agape.

Both translations flowed freely in a rhythm and happy fluency of narration; and, wherever he could, Tyndale upheld Luther’s doctrine of justification by faith. While in many instances the two translators Lust have reached the same conclusions independently, Luther’s strong influence on the father of the English Bible is unmistakable. Since Tyndale’s English translation makes up more than 90 percent of the King James New Testament and more than 75 percent of the Revised Standard Version, Luther’s legacy is still plain to see.

Luther was exceptionally gifted in many areas. But the aspect of his genius perhaps most responsible for his impact is the one least heralded: his skill and power as a translator and writer.

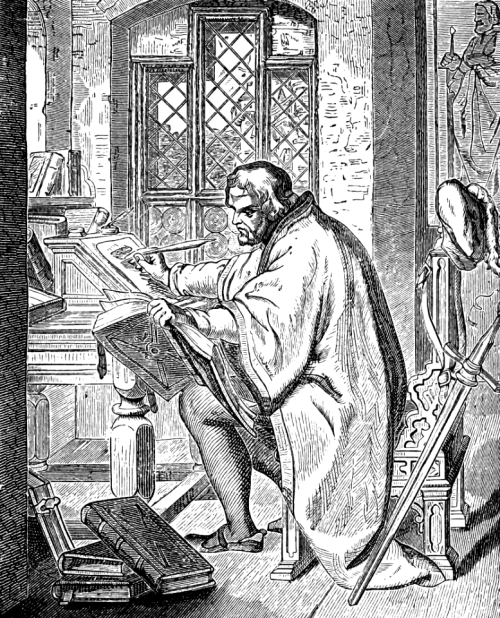

Illustration: Luther Translates the Scriptures via Creazilla, Public Domain