In our discussion of John Kleinig’s translation of J. G. Hamann’s London Writings, with which I was involved, I quoted part of Hamann’s account of his conversion to Christianity. I want to give you a sample of what comes next, in which Hamann confesses his newfound faith.

Hamann’s mature style, even when he writes about serious subjects, is comical, filled with wordplay and allusions, dense, and sometimes hard to decipher. John Betz, the author of the definitive book on Hamann, After Enlightenment: The Post-Secular Vision of J. G. Hamann, says that his style is purposefully counter to the straightforward, lucid style that characterizes the Enlightenment writers, thus making the point that reality is not as clear as the rationalists like to imply.

But the London Writings, written at the very beginning of his career as his personal reflections, are highly readable, making them the best introduction to the writings of Hamann, especially since here he formulates the ideas that he would develop in more detail later. Hamann’s prose in these journals is passionate, incisive, and electric with discovery. All of this is conveyed in Dr. Kleinig’s superb English rendition.

From “Thoughts on the Course of My Life,” London Writings, p. 291:

I conclude, from the evidence of my own experience, with heartfelt and sincere thanksgiving for His saving Word which I have tested and found to be the only light by which we not only come to God, but also get to know ourselves. It is the most precious gift of God’s grace that surpasses the whole natural world and all its treasures as much as our immortal spirit surpasses the clay of our flesh and blood. His Word is the most amazing and venerable revelation of the most profound, most sublime, most wonderful mysteries of the Godhead, whether it be in heaven, on earth, or in hell, the mysteries of God’s nature, attributes, and His great, bountiful will chiefly toward us poor people, full of the most significant disclosures throughout the course of all the ages until eternity. His Word is the only bread and manna for our souls, which a Christian can no more do without than the earthly man can do without his daily necessities and sustenance — — yes, I confess that this Word of God accomplishes just as great miracles in the soul of a devout Christian, whether he be simple or learned, as those described in it. I confess that the understanding of this book and faith in its contents can therefore be gained by no other means than through the same Spirit who inspired its authors and that His unutterable sighs which He creates in our hearts are of the same nature as the inexpressible images that are scattered throughout Holy Scripture with a greater richness than all the seeds of the natural world and its realms.

Secondly, I confess with my heart and my best understanding that without faith in Jesus Christ it is impossible to know God and what a loving, unutterably good and generous being He is, He whose wisdom, omnipotence, and other attributes seem to be only, as it were, instruments of His love for humanity. I confess that this preference for people, the insects of creation, belongs to greatest depths of divine revelation. I confess that Jesus Christ was not only pleased to become a man, but also a poor and most wretched man. I confess that for us the Holy Spirit has published a book for His Word, in which, like a fool or a madman, yes like an unholy and unclean spirit, He turned proud reason’s children’s stories, trivial, contemptible events, into the history of heaven and God (1 Cor 1:25). I confess that this faith shows us that all our own deeds and the noblest fruits of human virtue are nothing but the sketches from the finest pen under a magnifying glass or the most sensitive skin as seen under it. I confess that it is therefore impossible for us to love ourselves and our neighbor without faith in God which His Spirit produces and without the merit of the only Mediator. In short, a person must be a true Christian to be a proper father, a proper child, a good citizen, a proper patriot, a good subject, yes a good employer and a good employee. I confess that every good deed, in the strictest sense of the word, is impossible without God, and that He indeed is its only author.

There is a lot to unpack here, and he unpacks it in his later writings, beginning with the other works that constitute the London Writings. Notice here how he even brings up vocation!

After his transforming encounter with the Word of God, Hamann found a German Lutheran church in London. He confessed his sins to the pastor, received absolution, and that Sunday received Holy Communion. He met with the pastor for counseling, who told him, “go home.” He did, and the next chapter of his life unfolded.

I’ll tell more about what transpired, which is recounted in “Further Thoughts on the Course of My Life” at the very end of the London Writings, including his romance with the sister of his friend, Katharina Berens. I’ll do that in context of trying to explain why Hamann has become so important for contemporary thought.

Note: Yes, the book is expensive at $75, though you can get it for $65 at the Ballast Press website. It’s 473 pages, and it took 5 years to prepare. Scholarly-level books often are expensive to produce, and they sell to a limited audience. (Though I think this one has the potential to reach a broader audience.) This is a book to read, re-read for your devotions, underline, and return to again and again.

If it is too much for you to buy but you still want to read it, ask your library–either your public library or, especially, if you are connected to a seminary or university research library–to order it. Libraries are, as someone has said, the big market for expensive scholarly books. Once the book get reviewed in academic journals, this will start to happen. This is a primary source by a major figure in Western thought, so I am confident about that. In the meantime, you can get the first edition.

Buy the book at Amazon or at the Ballast Press website (where it is actually a little cheaper).

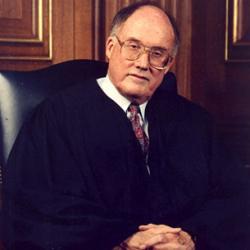

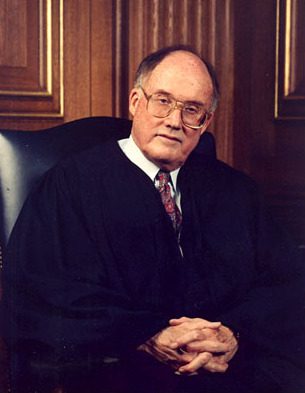

Illustration: Portrait of J. G. Hamann by unknown artist (1775-1778), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons