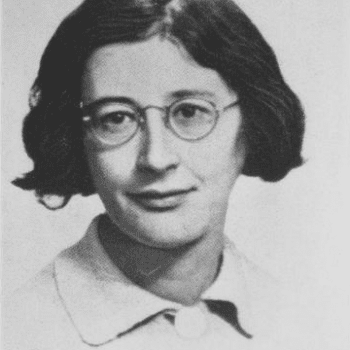

Simone Weil (pronounced “Vay”) was a French thinker who converted from Judaism to an idiosyncratic, mystical Christianity. In her short life (1909-1943), she was a radical leftist, worked with the French resistance to the Nazi occupiers, and had a dramatic conversion experience when she contemplated George Herbert’s poem on human sin and the grace of Christ, Love III. (See my book Reformation Spirituality: The Religion of George Herbert.)

Through it all, Weil always worked, not just with her mind but with her hands, including a long stint in an automobile factory. She wrote a great deal about the importance and value of working. And her insights tie in interestingly to Luther’s doctrine of vocation.

Richard Gunderman sums up her thoughts on the matter:

Weil looked at work as more than an exchange of money for labor. She argued that people need to work not only for income but also for the experience of labor itself. From her perspective, money does not solve the core problems of joblessness. Instead, work provides vital opportunities to live more fully by helping others. . . .

Though Weil understood that people need work to live, she argued that labor fulfills other equally essential functions. One is the opportunity it offers to become more fully focused and present in living. To multitask is to live superficially, but those who are completely present with another can give fully of themselves. She called attention “the rarest and purest form of generosity.”

Weil believed that humans are not cut out for lives of idle pleasure. It is through work, whether in agriculture, manufacturing, the service industry or maintaining a home and raising children that people contribute to the lives of others. Work reminds us, she wrote, that individuals are part of something greater and provides a larger purpose to live for. She wrote of the calling to serve others:

“Anyone whose attention and love are really directed towards the reality outside the world recognizes at the same time that he is bound, both in public and private life, by the single and permanent obligation to remedy, according to his responsibilities and to the extent of his power, all the privations of soul and body which are liable to destroy or damage the earthly life of any human being whatsoever.”

Work must be seen in its larger context, for if it isn’t, laborers may soon feel like cogs in a machine, winding a nut onto a bolt or moving papers from an inbox to an outbox. To do work well, people need to understand the context of work and how it makes a difference in the lives of others.

Here is Luther’s emphasis that, while vocation is important to our own well-being, the purpose of all of our vocations is to love and serve our neighbors. She also has Luther’s understanding that God is in vocation, that He loves and blesses those whom He has created through us.

Here is how the Wikipedia article about her describes her insights about loving God and loving our neighbor:

In Waiting for God, Simone Weil explains that the three forms of implicit love of God are (1) love of neighbor (2) love of the beauty of the world and (3) love of religious ceremonies.[70] As Weil writes, by loving these three objects (neighbor, world’s beauty, and religious ceremonies), one indirectly loves God before “God comes in person to take the hand of his future bride,” since prior to God’s arrival, one’s soul cannot yet directly love God as the object.[71] Love of neighbor occurs (i) when the strong treat the weak as equals,[72] (ii) when people give personal attention to those that otherwise seem invisible, anonymous, or non-existent,[73] and (iii) when we look at and listen to the afflicted as they are, without explicitly thinking about God—i.e., Weil writes, when “God in us” loves the afflicted, rather than we loving them in God.[74] Second, Weil explains, love of the world’s beauty occurs when humans imitate God’s love for the cosmos: just as God creatively renounced his command over the world—letting it be ruled by human autonomy and matter’s “blind necessity”—humans give up their imaginary command over the world, seeing the world no longer as if they were the world’s center.[75] Finally, Weil explains, love of religious ceremonies occurs as an implicit love of God, when religious practices are pure.[76] Weil writes that purity in religion is seen when “faith and love do not fail,” and most absolutely, in the Eucharist.[77]

She is also interesting on the subjects of beauty and of suffering. Again, from Wikipedia:

For Weil, “The beautiful is the experiential proof that the incarnation is possible”. The beauty which is inherent in the form of the world (this inherency is proven, for her, in geometry, and expressed in all good art) is the proof that the world points to something beyond itself; it establishes the essentially telic character of all that exists. Her concept of beauty extends throughout the universe: “we must have faith that the universe is beautiful on all levels…and that it has a fullness of beauty in relation to the bodily and psychic structure of each of the thinking beings that actually do exist and of all those that are possible. It is this very agreement of an infinity of perfect beauties that gives a transcendent character to the beauty of the world…He (Christ) is really present in the universal beauty. The love of this beauty proceeds from God dwelling in our souls and goes out to God present in the universe”. She also wrote that “The beauty of this world is Christ’s tender smile coming to us through matter”.[66]

Beauty also served a soteriological function for Weil: “Beauty captivates the flesh in order to obtain permission to pass right to the soul.” It constitutes, then, another way in which the divine reality behind the world invades our lives. Where affliction conquers us with brute force, beauty sneaks in and topples the empire of the self from within.

Though she is quite Christ-centered, she is not completely orthodox. She is extreme and aesthetic in her pursuit of virtue. She said that Hinduism and Buddhism also “deliver me into Christ’s hands as his captive,” and yet she opposed syncretism.

She was most interested in Catholicism, but she never became a Catholic. I was under the impression that she refused to be baptized out of a sense of solidarity with those who were not inside the church, but while that was true for awhile, the Wikipedia article said that she finally was baptized shortly before she died of tuberculosis at the age of 34.

Her take on Christianity is so unusual, yet substantive, that she might get through to that “None” friend of yours who is “spiritual but not religious.”

Photo: Simone Weil by Unknown photographer / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons