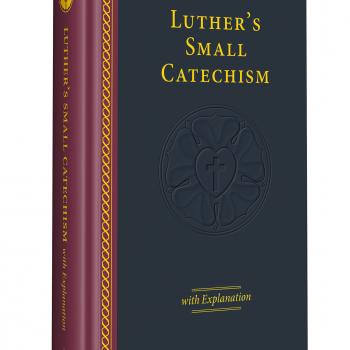

Concordia Publishing House celebrated its 150th Anniversary yesterday. Though CPH now offers some 10,000 products, its foundational publication has always been Luther’s Small Catechism, one of the most succinct and eloquent explanations of Christianity in all of Christendom, designed both to teach the faith to young and old and to serve as an inexhaustible devotional manual.

Concordia Publishing House celebrated its 150th Anniversary yesterday. Though CPH now offers some 10,000 products, its foundational publication has always been Luther’s Small Catechism, one of the most succinct and eloquent explanations of Christianity in all of Christendom, designed both to teach the faith to young and old and to serve as an inexhaustible devotional manual.

In honor of this celebration and as an example of both the continuity and the innovations that characterize the ministry of CPH for the last 150 years, I want to draw your attention to the new edition of Luther’s Small Catechism with Explanations, now also available as an app for your phone!

Historically, the catechism used to instruct Christians consisted of three major texts: the Ten Commandments, the Apostle’s Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. Then various explanations and questions & answers used in teaching these texts became attached to or even took the place of those primary documents, resulting eventually in various “catechisms” according to the different Christian traditions.

Medieval catechisms tended to follow the order of the Creed, the Prayer, and the Commandments, emphasizing that obeying the Law is the main focus of the Christian life. Luther put the elements in a different order: First Law (the Ten Commandments); then the Gospel (the Creed); and then the relationship with God in the Christian life (the Lord’s Prayer). Luther also added the Biblical texts regarding Baptism, Confession and Absolution, and the Lord’s Supper. He also attached a “Table of Duties,” consisting of Biblical passages about vocation. Catechumens learned the Word of God, with Luther’s catechism helping them to personally understand and apply that Word, so that they could answer the repeated question, “What does this mean?”

Luther’s Small Catechism is, indeed, “small”–it has been printed in a tract of only 24 pages–making it a marvel of theological brevity, yet richness. But it has often been accompanied by commentary, proof texts, and other material.

Lifelong Lutherans will remember the blue book and later the maroon book they used in confirmation, the Small Catechism with Explanations that go back to the work of Heinrich Schwan (1819-1905), the third president of the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod (who is credited by Wikipedia–incorrectly [see comments]–with installing America’s first Christmas tree in a church).

In 2017, CPH published the Catechism with new explanations. It would never have occurred to Rev. Schwan that Christians would have to deal with controversies over abortion, euthanasia, homosexuality, same-sex marriage, cohabitation, and the like. The new explanations apply the Cathechism–as well as an abundance of Scriptural passages–to those issues, as well as other 2st century concerns.

What is most striking to me is the new edition’s organization. Each part of Luther’s Catechism is followed by an explanatory section “The Central Thought” followed by “A Closer Reading of the Small Catechism,” giving additional explanations and Scriptural support for what Luther was teaching. Then follows a section “Connections and Applications,” which applies the teaching to our lives today. Because the Catechism’s purpose is not just educational and doctrinal but devotional, the treatment of each part ends with a Psalm, a hymn, and a prayer.

Notice the structure: we move from learning the content, to understanding the content, to applying the content. This follows the tenets of classical education (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and makes for unusually thorough learning. Luther’s Small Catechism with Explanations thus functions as a stand-alone curriculum for teaching the faith. In addition to being a doctrinal and moral reference book and a devotional manual.

I know, I know, this new edition came out two years ago, but we just discussed it in a reading group of area church workers that I take part in. Though I was one of the many readers of the material as it was being prepared, I didn’t really study the final product before now.

We also read two articles from a special issue of the Concordia Journal on the Catechism that I would recommend: Gerhard Bode’s Knowing “How to Live and Die: Luther and the Teaching of the Christian Faith” (on Luther’s writing and use of the Catechism) and Pete Jurchen’s “Why Luther’s Small Catechism with Explanations Is a Tool Uniquely Suited for Parish Education” (by one of the editors, explaining how this edition was designed and how it can be used to teach the faith).

And just as the original Catechism made good use of the media technology of its day, namely, the printing press, this new version is also making good use of today’s media technology. The app for Luther’s Small Catechism, updated last month, includes additional study and devotional materials. It also allows for easy sharing of passages on social media and e-mail. It also includes translations in various languages.

The app for Luther’s Catechism itself is free, but if you want the new explanations and accompanying material from the 2017 edition, which is 429 pages long in the hard copy, that costs $7.99.

Go here for the Android version.