I like antibiotics and air-conditioning, and I’d like to keep them.

Many knowledgable people agree that we probably wouldn’t have either–or have many other worthwhile things–without Nominalism. I agree.

When I first heard that Nominalism maybe the culprit behind the disenchantment of the world, it seemed right to finger it for blame. But when I heard secularists give credit to Occam’s razor for contributing to the rise of science as we know it, the last of my reservations fell away.

But it left me with a problem, the one I’m sure you can see from what I said a moment ago. Science has made the material conditions of our lives better in many ways even as spiritual conditions have gotten worse. We now lead seemingly meaningless lives in conditions the ancients would have considered palatial.

Can we have it both ways? Or must we choose one or the other: either lives of ease amid plenty with nothing to live for, or spiritually rich lives that also tend to be brutish and short?

Christian defenders of Nominalism

Some folk defend the Nominalists by pointing out that they shouldn’t be blamed for unintended consequences; Nominalists had good intentions. They weren’t out to bleach the world of meaning.

I sort of agree with that. The consequences, both bad (the death of meaning), and good (science) were unintended. But that misses the problem. Here’s the problem: What now?

One way to have it both ways is by privatizing meaning. (That’s self-defeating because it gives away the stuff that makes selves possible.) Fundamentalism is another way to deal with the problem. It superimposes a heteronomous Word upon the stuff of life and culture. It can’t help but come across as alien and oppressive though. (Fundamentalism seems to produce as many atheists as believers.)

Two analogies that I find helpful (I coined them both…feel free to use them if you’d like.)

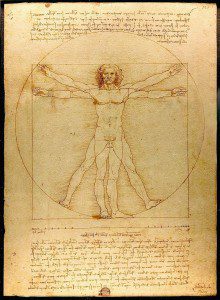

Because science is a quest for knowledge without reference to us, it necessarily loses a sense of human scale as our instruments of measurement grow more powerful. But meaning is all bound up with human scale. Meaning is occupied with the question, “What is the good life?” And since we live our lives in bodies, meaning must be discovered at the level of human scale. If you can accept this, then these two analogies may appeal to you.

Proper viewing distance

When you go to an art gallery the works are situated so as to facilitate proper viewing distance. This is tacit knowledge, embedded into the conditions for viewing. You don’t need to think about it, the thinking was done for you.

If you are too far away from a work, you can’t receive it properly, the meaning is lost with the increase in distance. The same goes for getting too close.

We are placed in the world with faculties that are appropriate to our place in it. Our senses serve our lives, not only by helping us survive, but by helping us to live meaningfully. When we pull back or get too close, we can lose our orientation and lose a sense of meaning.

There has been a revival of interest in human scale in architecture and tool making. (New Urbanism and ergonomics are what I’m thinking about.) But this point is larger, it presumes that our bodies and our universe were made for each other.

Does this make science, with its out-sized instruments for measuring the cosmos, somehow wrong? No. But we need to think about what we’re doing.

Artists know their media and they work with them knowledgeably, if not altogether consciously, to create works scaled to the embodied reception of those works. Science takes us into the realm of pigment mixing and brush making. It takes us into the world of meaning making. This can work itself out in two ways. We can either co-create–taking the forms already given by God and working harmoniously with them. Or we can attempt to overwrite those forms and dehumanize and deface the world.

How can we do science without doing the latter?

Science is basketball

If I were to run up to you and knock things out of your hand, or move back and forth laterally to keep you from getting to your goal, you’d probably think I was joking. But if I kept it up, you might call the police.

On the other hand, if you were to walk casually through a basketball game on your way somewhere and you got in the way of play, people on the court would consider you rude, and if the stakes were high (maybe there’s money on the line for the winning team), you might even get beat up. (Basketball is my sport of choice, but you can substitute your favorite if you’d like.)

Science is like basketball in this way. On the court of scientific study, rules apply that don’t apply off the court. Conversely, many of the rules that govern our lives and give them meaning are suspended. A scientist may study biochemistry all day long, but when he goes home he doesn’t treat his wife as though she were just a machine made of meat. She’s his wife and he should treat her as such. (If he were to attempt to fix electrodes to her skull at the dinner table it could lead to conflict.)

Now which is more real–biochemistry or the embodied life of a human being?

Every humane scientist knows the answer intuitively.