The Myth of the Cave

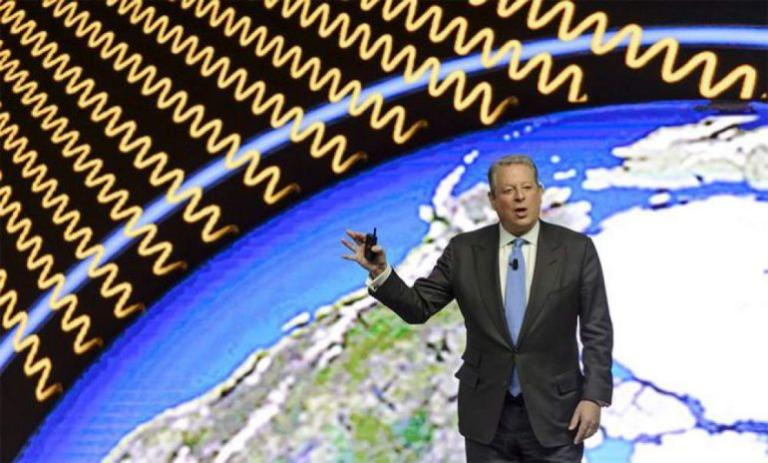

As I watched An Inconvenient Sequel I felt a need to reach for Plato in order to review his thoughts on why images can’t be trusted. Now that should get you thinking of the best known part of The Republic, the Myth of the Cave. I could identify with it. As I looked at the shadows being cast on the wall, alongside the others who were similarly chained to their seats, something in me rebelled, and I felt a need to get up and walk out of the darkness.

You may remember that in Plato’s story the man who does that comes back to bring a report from a sunlit land outside the cave. But things don’t go well for him. The discomforting light he shines into their eyes is resented and he’s attacked. If you’re a climate change agnostic, like me — or worse, a skeptic, like some of my friends — you’re used to this sort of thing:

“He doesn’t care about the planet!”

“He’s stupid!”

“What a callous ass! Think of all those people dying in those preventable hurricanes!” (Yep, preventable.)

“Get him!”

If you’d like to drag me to your pillory just now, I advise calm. For one thing, your strident impatience raises suspicion. Years ago, when I worked in the inner city, I heard a lot of sad tales that I, only I, could bring to a happy conclusion. But I had to act right now! No time for thought! No time to question! Just cough up the money! Delay only proved that I was unfeeling and probably evil.

What I learned the hard way, more times than I care to recount, is the more impatient the demand to act, the more likely a scam is going on.

At the Temple to the Climate

A temple to climate change seems to have been raised on questionable foundations. They even appear to have a quasi-religious character, more articles of faith than simple facts. I’d like to dig them up and think about them a little. (By the way, the term “true believer” was used positively by one of the directors of the film in his comments following the screening, thereby demonstrating both his ignorance of its provenance — the book by Eric Hoffer — and the fact that Hoffer used it pejoratively for people who are dangerous ideologues.)

Here are some questions begged in the film that I think are worth questioning.

The Climate Isn’t Supposed to Change

Obviously, responsible scientists don’t believe this. But I’m not talking about them. I’m referring to the man in the street. The man in the street is constitutionally conservative, even when his politics are left-wing. Change unnerves him, like hard turbulence on a cross-country flight. His alarm makes him susceptible to suggestion.

But scientists tell us that our planet has had remarkable climate change over its history. I used to live on a sandbar that scientists believe was formed by a receding glacier at the end of the last Ice Age. I’m speaking of Cape Cod. It’s a beautiful place. From my perspective global warming was a good thing in that instance. But I know what you’re thinking, “You moron, think about the damage climate change brings!” I think damage here can be broken down into two categories—damage to the environment, and more directly, damage to ourselves. Let’s look at each:

Nature is fragile

Well, yes it is, and no it isn’t. It depends.

Yes, people can change the physical environments they live in for the worse. Just take a look at Haiti from space. That orange ring surrounding it beneath the water is the once fertile topsoil that was washed away after deforestation. But even Haiti can heal in time.

But nature, remember, is often the perpetrator of damage as well as the victim. I recall seeing the devastation following the Mount St. Helen’s eruption. For miles around the place looked like the industrial wasteland left by the mining of the oil sands in Alberta, Canada. But today, to the untrained eye, it looks like nothing happened. There are trees, and flowers, and wildlife. Does this justify harvesting the oil sands of Alberta? I’m not saying that. But it does put it in a different light, and I think a clearer one.

People die in hurricanes because of climate change

Yes, Mr. Gore put it that baldly. But severe weather has been with us for a long, long time. The thousands of people who died in Galveston, Texas in 1900 died needlessly. But not because of climate change as Al Gore thinks of it. If there had cameras recording the event, a voiceover blaming climate change could be no more substantiated than the claim that the Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 was.

The reason the folks died at Galveston had something to do with being on a sandbar off the coast of Texas. Maybe a global movement should be underway to make coastal regions safer? It seems to me that the correlation between better levies and few hurricane deaths is easier to prove that any such claims for lower CO2 levels.

Is severe weather getting worse? Possibly. But our data sample is pretty small. The planet has been killing people far, far longer than we’ve been recording temperatures. Maybe more people are living in places where severe weather can kill you. Maybe it is a combination of many factors.

People can be morally spotless

When it comes to morality, human beings just muddle along. We will never build Utopia. (By definition it doesn’t exist.) Instead every choice is a kind of tradeoff. And we don’t always get to choose between good and bad. Sometimes it is between good and better, or just one pretty-good thing and another pretty-good thing. Hopefully the goods we choose are better for us than the choices we don’t make. But we can’t be sure of that sometimes.

Take Mr. Gore’s film. Ostensibly it is about choosing in favor of the environment. But what the film leaves to our imaginations is the very real people who suffer when this choice is made. For example, I’m thinking of all the people who have been left behind in West Virginia and in other places that depend on coal mining. The only time this is hinted at is by dismissive abstractions like “the fossil fuel industry.” That brings to mind cigar-puffing fat cats. But what I think about is working people who have taken pride in their work for generations. They are Untouchables now, and invisible to the beautiful people. Donald Trump comes up a lot in the film as a sinister and ignorant fellow. But if Mr. Gore of An Inconvenient Sequel is the Lorax who speaks for the trees, then why isn’t Mr. Trump Horton from Horton Hears a Who? The Whoville of Mr. Trump’s story is situated in West Virginia where people are so economically tiny that people in New York, Washington, and San Francisco don’t believe that they even exist — or have a right to.

This brings me to my favorite part of the film. (Yes, I have a favorite part.) At the Paris Agreement, the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, demonstrating he understands The Art of the Deal, threatens to build 400 coal-fired power plants unless he gets concessions from Western nations on loans. Mr. Gore, seeing his chance, strong-arms the owners of Solar City to give away proprietary technology to the Indian government. (Prediction: India will soon be a big exporter of cheap solar panels.) The gist of Modi’s argument is powerful, and to my way of thinking, persuasive. Essentially it is this: isn’t it convenient that the West gets 150 years of cheap, dirty energy to build a civilization that now dominates the globe and just when India, using the same technology, begins to challenge that dominance, there is a global climate change crisis?

Less cynically, Modi turns morality back on the West during his speech at the Paris Climate Talks, he put it this way, (I’m paraphrasing): “I have 300 million people without power in my country. And you tell me that building 400 coal-fired electrical plants is immoral? I tell you leaving them without power is immoral!”

This is what I mean by trade-offs.

But science makes us certain!

Actually, no. Scientific forecasts give us probabilities, not certainties. But most people don’t look to science for that.

Climate scientists are not time travelers from the future who have come to warn us about something that has actually happened fifty years from now. They’re not reading the entrails of a goat, either. They occupy a space somewhere in between. And the more actual history they have to work with, the better their forecasts tend to be. Furthermore, scientists are often surprised by what they see when they look at real events. The math and computer models can only take you so far.

And I won’t list for you all the scientific red herrings and false alarms I can remember just in the course of my lifetime. Even the climate change crisis isn’t unprecedented. I remember the Club of Rome and The Limits to Growth like it was yesterday. Their fevered predictions of overpopulation and mass famine didn’t come to pass, but they did keep Charlton Heston working for about a decade: Omega Man, Planet of the Apes, and my favorite, Soylent Green. Fun stuff. Please forgive my lightheartedness concerning something so many people take very seriously, but once burned, twice shy. I just don’t believe scientists are infallible.

If this bothers you, see my previous point about muddling through. If you can’t bring yourself to do that, I recommend getting religion. But whatever you do, don’t make climate change fever your religion. And this brings me to my conclusion and the Reverend Gore’s.