There are many ways through the dark valleys of depression, and prayer must be one of them. The problem is that the depressive often cannot even stir to perform regular prayer. Simple tasks become a burden. Prayer routines fall by the wayside. Commitments are left undone.

And with each little failure, the walls close in tighter and the sufferer sinks deeper.

Perhaps one way through the dark valley is to follow the trail laid down by our ancestors with the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. The Psalms have within them the entire range of human emotion and experience. If the regular routine of prayer no longer works for us, if the liturgy of the hours or the rosary or whatever discipline we try to follow has become a drudgery and burden, then we have to find a new way to speak to God and, more importantly, let God speak to us.

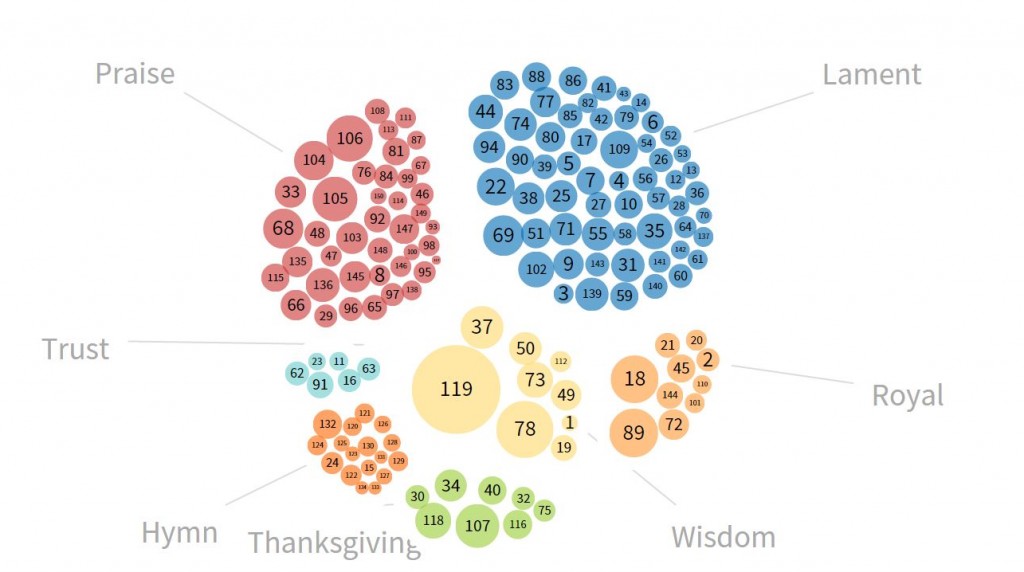

Fifty-nine psalms—more one-third of them—have elements of Lament. It would appear, on the surface, to be utter folly for the person in the midst of a soul-crushing sorrow to enter deeper into a world of despair. That appearance is deceiving, however.

The laments are more than that. They are a dialog between man and God. They are a howl of sorrow, yes, but they are also a plea, a thanksgiving, and a sigh of hope and trust.

Perhaps we need a Depression Psalter: something to give voice to pain, speak to God, and express our hope. It could be part of our cold reboot of the soul, as we dispense with old habits, including habits of prayer, and engage cross and the desert head-on. Let me begin with Psalm 13. It opens with a question that, as so often in the psalms, is an accusation:

1 How long, O Lord? Wilt thou forget me for ever?

How long wilt thou hide thy face from me?

2 How long must I bear pain in my soul,

and have sorrow in my heart all the day?

How long shall my enemy be exalted over me?

You can see in the repetition of “How long” the urgency and pain of the psalmist, while parallelism builds gradually sharper accusations against the Lord. A common feature of Hebrew poetry is to say the same thing twice in different ways, which has the effect of both echoing and amplifying points.

At first, the speaker asks how long the Lord will “forget” him, suggesting that his distress is not the direct action of God, but mere neglect.

In the next line, however, God has chosen to actively “hide thy face.” God has not forgotten the speaker: God has deliberately turned away from him. These mounting accusations are a more circumspect way to accuse Yahweh for his present plight

The pain in our souls and the sorrow in our hearts is as good a depiction of depression as you’re likely to find. This is De profundis clamavi: a cry from the depths.

Finally, we have the characterization of the enemy who is exalted over us. We can read “enemy” in many ways. It could be the world, the flesh, and the devil (mundus, caro, et diabolus): the inverted Trinity that leads us into darkness. Any one of these things may be at the root of our depression: stresses of life present and past (the world), challenges from our body from illness or temptation (the flesh), or the evil one himself, who must not be discounted as the root of some cases of severe depression.

But I think it may be more useful for those who suffer from true clinical depression to see the enemy as the depression itself. It’s not unusual to give personality and even character to depression. That’s why it’s called the Black Dog. This runs the risk of placing the depression outside ourselves rather than something that springs from within, but it can also be useful for understanding and confronting the forces pulling us down. In prayer, confronting our depression as an Other, an enemy, is just one way to reach out to God and articulate our pain. It says that we are not our illness, and it will not define us, and it allows for us to plead for this enemy to be driven away.

The next section is a prayer for help. We are asking for deliverance from the enemy, in this case, our depression.

3 Consider and answer me, O Lord my God;

lighten my eyes, lest I sleep the sleep of death;

4 lest my enemy say, “I have prevailed over him”;

lest my foes rejoice because I am shaken.

The Hebrew word translated as “lighten my eyes” means to shine, dawn, or give light. It is a powerful way of asking for darkness to be driven away, but it also suggests enlightenment and spiritual wisdom. We are asking God not merely to drive away the pain, but to give wisdom to our souls so we may live better, and to bring the Light Himself to dwell within us.

And to make the stakes clear, God is warned that our very lives are at risk. Major depressive disorders are, in fact, a serious, life-threatening condition. Too many people today fail to understand this.

Again, we have the personification our of our pain as our “enemy” and our “foes.” We are pleading with God not to let them triumph.

The final section is common in Psalms. It’s a prayer of trust, hope, and gratitude for all the Lord has already given and will give:

5 But I have trusted in thy steadfast love;

my heart shall rejoice in thy salvation.

6 I will sing to the Lord,

because he has dealt bountifully with me.

This is key. Trust and rejoice! Whatever bears us down, the Lord bears us up. The Lord’s love is steadfast, and He will save us. We cannot despair.

However slender that reed of hope is, we must hold onto it and not be swallowed up by the darkness. We must trust and hope in the Lord. We must never give up on Him, even when we’ve given up on ourselves. If the Psalms teach us nothing else, they have to teach us that much.