When I was in college, some group or the other sponsored a blood drive. I’d never donated before, so when the nurse told me I had type B, I was mildly surprised. Everybody before me and after had been type O, that of the universal donor. I’d just assumed I would be too.

When I was in college, some group or the other sponsored a blood drive. I’d never donated before, so when the nurse told me I had type B, I was mildly surprised. Everybody before me and after had been type O, that of the universal donor. I’d just assumed I would be too.

Later, when I asked my father, a doctor, he said that I’d inherited that blood type from him. It’s not the rarest, but he laughingly told me that I’d better not get into any accidents in a small town.

I looked into things a little further, and found that while I could receive blood from type O, in an emergency situation, I could not live forever on it. I had to have my own type eventually.

So the size of the town that I could have an accident in could be smaller by at least that much—enough to have a good supply of type O, even if they didn’t have much type B. I could be sustained for a time, but then I’d need to get somewhere bigger. I mused that this would be the size of town with a Pizza Hut but no Applebee’s.

Of course, all this would be dependent upon the skill of the emergency room doctor. He’d have to get me going on type O to see me through the crisis. If he was hesitant and wanted to ship me off to a bigger place—so that someone could start me out with my own type rather than improvise for the time being—I’d run the risk of bleeding out.

Maybe I would make it and maybe I wouldn’t. It all depended on whether he would make do.

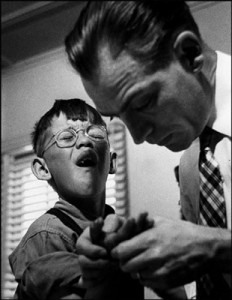

Now for the transition to the higher meaning: I returned to my father asking about that ad hoc decision to use what was available, to utilize what would serve. He said that was the difference between doctors. Some would have the guts to move ahead with whatever was at hand. Some would not.

To put it another way—in an emergency, some would step forward, bend down, and use a pocket knife to open up the blocked trachea of a man lying in a cow pasture; some would hold back, stymied by the imperfect conditions. The man in the field was at the mercy of the other’s courage.

But then, on the other side of the emergency, another dilemma presented itself. What was made to suffice in the limited circumstances must necessarily be set aside when better options presented themselves

Making do has its place, but trying to turn insufficient means into a way of living, a mode of existence, is equivalent to attempting to survive on disaster rations. Man can make it for a while on bread and water alone, but higher authorities than I have said you can’t live on those two things for long.

That is the predicament that often presents itself, and it calls for two different kinds of vision and nerve. You must not be so paralyzed by a situation and its lack of perfection that it stymies all action whatsoever.

As the old saying goes, nothing would be accomplished if all possible objections must first be overcome. But then again, nothing can flourish if it is not provided with as many of the circumstances as possible that are meant to bring it to full flower.

It seems that a great quandary in every life is knowing when to start an endeavor. It never seems like the auspicious time. There are so many who counsel us to wait, filled with good reasons. Sometimes those are indeed the wiser voices.

But if there’s enough to get going; enough to prime the engine and find a good tail wind—and of course enough of the future to see your way through—then the initial impetus to go must be encouraged. Type B can get out of the blocks on type O.

Then, after the start, there comes a time when more must be provided. The proper environment must be found, the sufficient means located. Type B must find type B.

What has been a leg-up, a boost, must be let go of in favor of that which will sustain. Otherwise, what has started will stall out. A holding pattern cannot go on indefinitely, lest adequacy become the enemy of achievement.