The day before I left on vacation, the front page of the New York Times showed something (well, two things) unusual: black-and-white photographs.

The day before I left on vacation, the front page of the New York Times showed something (well, two things) unusual: black-and-white photographs.

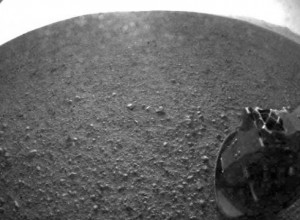

The photo on the left showed a gentle-sloped mountain rising from a desolate plain; on the right, vehicle tracks through rocky dirt. The composition of the photo on the left—framing, shape of mountain, spareness of other detail—reminded me of prints and paintings I’ve seen of Mount Fuji. But that’s not why I tore off the page, scribbled a few notes in pencil, and left it on my desk.

On July 20, 1969, I was seven years old. My parents and brother and I had flown down to Burbank to visit my uncle, the way we did every summer, for a week of barbecues, backyard-pool-swimming, visiting Disneyland, and smog.

My uncle lived in Arcadia, a town pressed up against the San Gabriel Mountains and one of the smoggiest parts of Los Angeles County. The gritty, brown air made for psychedelic sunsets. My brother couldn’t go outside without wheezing, so we played indoors with Matchbox cars on shag carpet. But I digress (easy for me to do about those days).

That Sunday in July, as all the grown-ups gathered around the TV, I hung back, not wanting to look.

The second unusual aspect of those New York Times front page photos a few weeks ago is the subject matter. The mountain, the tire tracks, the dirt, the desolate plain: Mars. The Mars rover, Curiosity, took the photo and made the tracks, controlled by computer commands from a lab in Pasadena, California, not too far from my uncle’s former house.

A quick online search yields several figures for the distance, but even one of the smallest boggles my mind. I don’t understand how a friend’s iPhone can read an email I type into a keyboard, let alone how digitized code can travel forty-eight million miles.

Back in 1969, I didn’t want the astronauts to land on the moon. I had nothing against them personally; when I imagined Apollo 11’s making a wrong turn or getting lost in outer space (danger, Will Robinson!), I did so to protect the moon rather than to injure the men aboard or to turn back science.

My desire, at age seven, was entirely focused and without larger metaphoric implications: Please, please don’t get there.

“Come see! This is history! You’ll tell your grandkids!”

I stood outside, watched the sky, preferring the smoggy opaque dome overhead to the image on the screen. I’d seen enough of how grownups mucked up planet Earth to wonder why they should do the same to the moon. When, years later, I wrote a story about the moon landing from the point of view of a nine-year-old girl named Robin, an editor who read the story admired the imagery, then told me, “We know Robin, we get her. We’ve all been her.”

Valid point about the loss of innocence, about a child thinking she sees what the adults don’t. Still, I’d never met—and still haven’t met—another person who watched the moon landing with the same degree of ambivalence and even dread as I did. If you’re out there, let me know.

And now we’re driving around the red planet, leaving tire treads and who knows what else. (Do rovers emit fumes?) I’m not arguing against this level of exploration, and I’m fascinated by the footage Curiosity beams many millions of miles to the lab in Pasadena.

But I remain haunted by that question that consumed me in 1969: Shouldn’t we get it right down here first?

Yes, we are endowed with curiosity. We can’t stay put anymore than we can breathe water. It’s in our created nature to taste that apple, to peek behind that curtain, to open that box. Curiosity may wreak havoc but it can also yield knowledge, discovery, intimacy, love.

I’m not advocating a return to cave dwelling or leeches as state-of-the-art medical treatment, but I do wonder about going places that our bodies aren’t naturally meant to go. And yet, using that logic, I’d never have boarded an airplane.

In 1969, I preferred fantasy to reality. I wanted green cheese, not actual rocks in the Smithsonian. I was drawn to the unknown, and I wanted the moon to stay far away. Conspiracy theories that the whole thing was filmed in a Hollywood back lot aside, the crackling black-and-white image on my uncle’s TV screen chipped away at the notion of some things being forever out of reach.

I still like make-believe—after all, I devote hours every day to writing fiction—though, as an adult versed in the nuances of adult mucking up, I like to think I don’t see the world as simplistically as I did at age seven.

So I’ll look at the pictures from Curiosity. I’ll read the stories of Pasadena scientists who have been suffering a kind of odd jetlag while living on Mars time (where a day is called a sol and lasts thirty-nine minutes and thirty-five seconds longer than here on Earth) while they “drive” Curiosity.

I’ll wonder how many people could be fed and schools funded with the zillions being spent by NASA. I’ll float between fascination and ambivalence, tethered by hope and skepticism and, yes, gravity.