Every year when I was young, as the vibrant colors of West Virginia’s fall foliage dulled to gray-brown, my dad would preach his sermon “Come Before Winter.” He did it for a number of years, and it became so popular that people in the region would abandon their home churches on that Sunday morning to come hear him preach.

Every year when I was young, as the vibrant colors of West Virginia’s fall foliage dulled to gray-brown, my dad would preach his sermon “Come Before Winter.” He did it for a number of years, and it became so popular that people in the region would abandon their home churches on that Sunday morning to come hear him preach.

Paul is under house arrest in Rome, writing to his protégé Timothy. He writes, “Come see me, and bring my cloak.” He says, “come before winter.” If Timothy doesn’t come before winter, he will have to wait till spring—Paul is old, not in the best health; spring may well be too late.

As I remember it, the sermon deals with several types of winter, including Timothy’s possible winter of lost opportunity and Paul’s imminent winter of death.

Paul is about to die and he knows it. Though his circumstances are dire, he appears to be quite content as he looks back on his life. He knows he has fought the good fight, finished the course. As death rises like a black wall on one side of him, his life spreads behind him on the other, no more possibilities, only hard established fact. He surveys it—and there are some ugly chapters, don’t forget—and he is content and happy with what he sees.

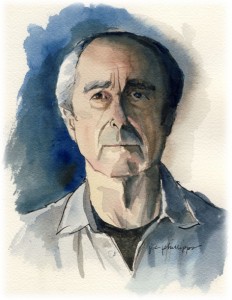

Earlier this year Philip Roth told an interviewer from the French magazine Les InRocks, he has put down his pen forever. He told them he is finished writing, is turning his back on it entirely. As a matter of fact, there is a Post-it note on the screen of his computer that says: The struggle with writing is over.

The note itself gives no indication of whether or not the end of Roth’s struggle is triumphant, or defeated, or some uneasy truce. In a New York Times article Roth explains that he sat and read back over his output and he is happy with it. He feels he has said what he has to say, and now he can kick back and fiddle with his iPhone. No kidding. He says he is playing with gadgets like a teenager, “Because I am free.” It sounds like contentment, or maybe relief.

This puzzles me. I look back over Philip Roth’s novels, famously autobiographical many of them, and this calm, content Roth in these interviews seems a stranger to the protagonist of the Zuckerman novels, or the short novels in which one story keeps rising to the surface: the aging man, dragging along baggage and estranged children and ex-wives, assessing his accomplishments and failures, seeking refuge from the onslaught of old age and death in the arms of much younger women. One of his protagonists complains that people call old age a struggle but he knows it’s not that, it’s a massacre.

That doesn’t seem to be the Roth of these interviews. This Roth says he will write no more, and he’s not kidding. He says the struggle is over, he is free.

John Updike wrote right up till the end. Joyce Carol Oates tells of how she sat by her husband’s deathbed, both of them toiling silently amid their separate flurry of manuscript pages. The nurse eventually couldn’t take it anymore, and she cried to them, “Don’t you know what is happening here?”

They both knew. He was at death’s door. But he felt he still had something to say, and so did she, so they kept writing. Leonard Cohen is still composing, and traveling the world putting on three-hour shows. At the age of ninety-seven, Herman Wouk has just published another novel, and cheerfully refuses to guarantee there won’t be more.

In a lecture on mythology, Joseph Campbell draws an arc and marks off the various stages of a human life as described by Dante in his Convivio. Youth lasts until the age of twenty five, and twenty five to forty five is the middle of life—thirty five of course is at the center of the arc. Seventy is the age at which we enter what Dante, pulling no punches, calls our decrepitude. This is the stage at which happiness is achieved in part by looking back on life with gratitude.

I can see how hanging up the tools of your calling could be a way of looking back with gratitude; I can also see how laboring on could be a way of looking back with gratitude as well, a way of being thankful that you found a life’s work that is meaningful, has value.

Paul finished the race, fought the good fight. He was ready to rest as winter moved in, and he had earned the right. Who could say Philip Roth hasn’t earned the right to some rest? Here’s to a happy decrepitude for Mr. Roth. Here’s to a happy decrepitude for Herman Wouk, and Leonard Cohen, and Joyce Carol Oates. Here’s to a happy decrepitude for all of us, every one.

Looking back with gratitude isn’t something that happens by chance. It’s not something you stumble upon. There appears to be one sure way to achieve it. I’ll explore that possibility tomorrow.