With sinister skulls on their black Metallica and Megadeth T-shirts, the teenagers who snaked alongside me in the queue to ride the Screamin’ Eagle roller coaster at Six Flags in St. Louis, Missouri, looked like diplomats of death to my twelve-year-old self. Only line dividers separated us as we waited in a series of sheltered areas, each one connected to the next by a flight of stairs that led the amusement park’s patrons ever closer to exhilaration—and perhaps death.

With sinister skulls on their black Metallica and Megadeth T-shirts, the teenagers who snaked alongside me in the queue to ride the Screamin’ Eagle roller coaster at Six Flags in St. Louis, Missouri, looked like diplomats of death to my twelve-year-old self. Only line dividers separated us as we waited in a series of sheltered areas, each one connected to the next by a flight of stairs that led the amusement park’s patrons ever closer to exhilaration—and perhaps death.

In first grade, I went to Worlds of Fun in Kansas City with my friend Jon, who told me about a roller coaster on the premises that had been shut down because one of the seating harnesses had failed, causing a rider to plummet to her doom. Fact or fiction, I thought about that every time I waited in line to ride a roller coaster.

I usually enjoyed the rides despite my dread, but the jaundiced skulls on those teenagers’ shirts only made Jon’s story seem more credible. Some skulls smiled, with canine teeth like vampires. Others had eyeballs that somehow managed to resist decay. They stared out of bony sockets at the living, leering and lidless. The skulls projected something manic and menacing all at once, as if they knew something in death the living could never know.

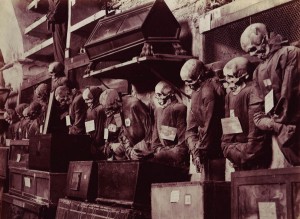

What was Death doing at Six Flags, walking alongside children who had snow-cone stains on their shirts? Surely the Grim Reaper would feel more at home at a cemetery or funeral home. A place like the Catacombs of the Capuchins in Palermo, Sicily would be even more ideal. Over 8,000 mummified dead are on display there, including the monks who created the site. If Death wanted to taunt tourists, he might seem less out of place there.

While the metalheads’ T-shirts set me on edge, other depictions of death at Six Flags did not faze me. Graphic images of the crucified Christ, to be precise, outnumbered skulls on T-shirts that day. Youth groups from all over Missouri, including mine, had traveled to attend a Christian music celebration at Old Glory Amphitheater.

As a Christian and the son of a minister, I thought of the crucifixion less as an execution and more as a prelude to eternal life. Looking back, I suppose it seemed peculiar to nonbelievers when they encountered Christians eating funnel cakes and riding roller coasters, all while wearing T-shirts glorifying a most gruesome death. Most shirts featured terrible taglines like, “His pain, your gain.”

Ten years later, I found myself wearing not a Christian T-shirt, but a black one not unlike those worn by the metalheads a decade prior. Instead of skulls, mine featured the spooky specter of spider-haired Cure vocalist Robert Smith, looking more ghoulish in life than most do in death.

I wore it to see the band on the Bloodflowers tour at Riverport Amphitheater in St. Louis in July 2000. For an encore, the band played a songs from 1983’s suffocating Pornography album, including, “One Hundred Years,” which opens with the line, “It doesn’t matter if we all die.”

Much as the Metallica and Megadeth T-shirts seemed out of sync with the spirit of Six Flags, it seems strange to me now that the existential anguish of the Cure’s music could draw people to a venue dedicated to entertainment—and yet there I was, moping with the masses. It did not seem all that anomalous to me then, as death and delight have never been far from one another in the Cure’s repertoire. The band released “The Lovecats,” a single inspired by Disney’s Aristocats, only a year after Pornography, after all.

But this pairing of death and diversion seems strange to me now.

These encounters with the macabre in pop culture unsettled me on some level. The skulls on the Metallica and Megadeth T-shirts made me think of Death as a grinning reaper rather than a grim one, and a being who wields his scythe in service of teenage rebellion.

Christian T-shirts, on one hand, reduce the suffering of Christ to sloganeering. Divorced from scriptural context, images of the crucifixion point to human barbarism instead of hope. The Cure’s vision of death as a meaningless thing, on the other hand, does not account for the sorrow of the living who lose loved ones and suddenly experience a vacuum that feels like a loss of meaning as much as a loss of life.

Above all else, these images of death felt dishonest to me, I suppose, because I experienced them in environments of entertainment. Diversion may make death more palatable, but it cannot bring the dead back to life, much less make them laugh. One can sing of death, too, but never make the grave less silent.

A more honest image of death may be the monks in the Catacombs of the Capuchins. I have only seen them in pictures, but the skeletal remains of these monks, still wearing their cowls, feel like portraits of death free of consumerism, diversion, and propaganda. In the Capuchin monks, I see the finality of physical death, but also what it looks like for a person to clothe himself in Christ unto the end.

But even more, the monks appear to smile (I suppose all skulls do to some extent). Perhaps, like the exoskeleton shells of cicadas, their smiling skulls point to the flight from this life and into the next. Perhaps their remains bear with permanent resolve the grins they bore as they escaped their earthly husks and drew ever closer to eternal exhilaration.

Chad Thomas Johnston is a slayer of word dragons who resides in Lawrence, Kansas, with his wife Rebekah, their daughter Evangeline, and five felines. He is a regular contributor to “Good Letters.” His writings have also appeared in The Baylor Lariat and at CollapseBoard.com, home to ex-Melody Maker critic/Nirvana-biographer Everett True. In May, eLectio Publishing released Johnston’s debut book, a whimsical memoir titled Nightmarriage.