Many years ago, my husband took a job in Rochester, New York, four hundred miles from our Boston home. Neither of us had ever been to Rochester, and we were apprehensive about the move. Our ten-year-old son was more than apprehensive: he was devastated. When we told him about the move, he burst into tears—because Rochester didn’t have a major league baseball team.

Many years ago, my husband took a job in Rochester, New York, four hundred miles from our Boston home. Neither of us had ever been to Rochester, and we were apprehensive about the move. Our ten-year-old son was more than apprehensive: he was devastated. When we told him about the move, he burst into tears—because Rochester didn’t have a major league baseball team.

The move was scheduled for the end of the summer. Sometime mid-summer, I decided I needed to start reading something long and engaging, as a stable grounding during the uprooting of the move.

Though a firm agnostic at the time, I chose Dante’s Divine Comedy. Despite my doctorate in English Literature, I’d never read it. (Well, maybe because my doctorate was in English Literature, the academy was pretty parochial in those days.)

Somehow we had John Ciardi’s three-volume verse translation on our shelves. So I started “Midway in our life’s journey” and continued from there, down into the Inferno. I was beginning my ascent through Purgatory when we loaded the U-Haul truck and drove west.

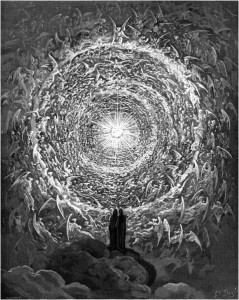

During the weeks of settling into our new home—arranging furniture, buying fabric to make curtains, finding a good grocery store, helping our son adjust to his new school—I reached the top of Purgatory and entered the dazzling light of Paradise. I stayed in Paradise while raking fall leaves—all the way to the final “Love that moves the Sun and the other stars.”

The Divine Comedy did just what I’d hoped and more. Not only did it give me something coherent to hold onto during the dislocating move; it gave me a fully envisioned cosmic worldview to move into and live within. I felt securely enfolded within the Divine Comedy, despite not believing at all in its Christian assumptions.

I was reminded of this episode in my life when I read Professor Carol Zaleski’s column “Rhymes and Reasons” in the February 19 issue of Christian Century. Zaleski traces the history of interpretations and translations of the Divine Comedy, coming to focus on the extraordinary number of translations in the past century.

This past century is known as the Age of Secularism, and most of Dante’s English translators during this era have not been “believers.” Zaleski asks: “What is Dante saying to readers who love the poem but reject the message? What is their devotion to Dante saying to us?”

Her tentative answer is that Dante’s continued popularity is “a sign that God is longed for and subliminally known.” A translator or reader cannot, she goes on, surrender to this poem and remain unchanged by it. “It seems unlikely that imagination and sympathy can be so deeply engaged without leaving traces in memory and planting seeds in reason.”

Was this my experience during that summer of moving to a new city? I remained a convinced agnostic for another few years. But I suspect that my immersion in the Divine Comedy did indeed “plant seeds” within me.

So did other works of art. I recall listening to Bach’s B Minor Mass with a subtle longing. The Kyrie, especially, sounded to me like a sustained ache for something I did not have.

One day I was driving to the mall and Vivaldi’s Gloria came on the radio. I pulled over into a parking lot, enthralled, hearing a joy that I longed to share.

Visiting the art museum in our new city, I stood in front of the medieval paintings of the Holy Family and let myself be drawn into them. I wasn’t just noticing the color techniques and the play with perspective that I’d been taught in my college Art 101 class. I was seeing a vision of love.

More than planting seeds was going on by then. Green shoots were sprouting in my soul. In fact, I began to use the word “soul,” which until then had been banished from my vocabulary.

By the time I started reading C.S. Lewis (whom I chose as my teacher about Christianity because he was an English professor like me, so I felt we shared at least that vocabulary), those green shoots were nearly in bud.

“The precise relationship between art and belief is a mystery and must remain so until we are imparadised with Dante,” Zaleski concludes.

Amen, I say. All I know is that exactly five years after my summer with Dante, I was walking the half-mile to our neighborhood Catholic church to begin preparation for baptism. The following spring, at the Easter Vigil, I was baptized.

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.