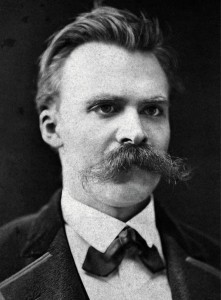

There’s a place in Nietzsche’s The Gay Science where he really lets Christians have it. Section 125 of Book III of The Gay Science is, in fact, where Nietzsche makes one of his famous pronouncements about the death of God.

There’s a place in Nietzsche’s The Gay Science where he really lets Christians have it. Section 125 of Book III of The Gay Science is, in fact, where Nietzsche makes one of his famous pronouncements about the death of God.

Nietzsche puts the claim that God is dead into the mouth of a “madman.” “Do we smell nothing as yet of the divine decomposition?” the madman asks, “Gods, too, decompose. God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.”

But the Section that struck me most recently is not about the death of God. It is, instead, Section 128 of Book III of The Gay Science. The heading of this Section is, “The Value of Prayer.”

“Prayer,” Nietzsche opens, “has been invented for those people who never really have thoughts of their own and who do not know any elevation of the soul or at least do not notice it when it occurs: what are they to do at sacred sites and in all significant situations in life, where calm and some sort of dignity are called for?”

It’s a good question. What are we to do at sacred sites and in significant situations that call for some dignity? How do we keep calm? How do we know what to do when we want to confront the sacred?

“To keep them at least from disturbing others, the wisdom of all founders of religions, small as well as great, has prescribed to them the formulas of prayers—as mechanical work for the lips that takes some time and requires some exertion of the memory as well as the same fixed posture for hands, feet, and the eyes.”

Nietzsche is having good fun at our expense here. Still, I can’t begrudge him the point. I, for one, do need formulas for prayers. I need mechanical work for my lips that takes some time. I require some exertion of my memory. I am deeply thankful to have fixed postures for my hands, feet, and eyes.

Without these prescribed things to say and do, I would, in fact, be rather at a loss in the attempt at worship and prayer. I would sit there dumbfounded. Or I would fidget and fuss. Many of us, myself included, do plenty of fidgeting during worship and prayer even with all the prescriptions.

At the end of Nietzsche’s hilarious prayer rant, he concludes, “What religion wants from the masses is no more than that they should keep still with their eyes, hands, legs, and other organs; that way they become more beautiful for a while and—look more like human beings.” You’ve got to love the italics on “keep still” and the reference to “other organs.”

The main point of prayer, as Nietzsche sees it, is to get the vast lot of pathetic humanity to sit down, shut up, and try not to fart for at least a few minutes.

Amen.

But for all the humor and contempt, could it be that Nietzsche reveals something of his own frustrated hopes and desires in this Section of The Gay Science? Prayer, says Nietzsche, was invented for those who do not know any “elevation of the soul.”

Prayer is for those pedestrian folk who “do not know what to do.” Rare souls (persons more like Nietzsche himself, presumably) do not require the mechanical work of prayer and meditation.

What a little boy Nietzsche is in these thoughts. He is like all of us who’ve wanted something elevated, something grand. Not finding anything grand in church or at sites of worship, we proceed to throw tantrums. We manifest our disappointments.

In this, I welcome Nietzsche as a fellow sufferer. He wanted something elevated and he got rote memorization and lots of kneeling and standing up. He wanted to see the face of God and was told, instead, to keep his bodily organs under control during the homily.

So Nietzsche threw a tantrum. That his tantrum consisted in a handful of books that are among the most brilliant rants against man and God ever conceived was simply our undeserved good luck.

Read Section 128 of Book III of The Gay Science again and a sympathetic fellow emerges from the bluster and bombast. He wants to know if this existence we’re faced with is really it. He hopes not. He desperately wants something grand out of human experience. He cries out against the world, “Is this grey place the sum total of our aspirations?”

He observes the people of prayer and suspects a trick. Where is the elevation of spirit here? The work of prayer seems, to Nietzsche, to be the very opposite of elevation. According to Nietzsche, the vast herd of prayerful people seem simply to have given up. They take the world as it is. They dumbly accept it as a gift.

A strange gift.

Trudging along, those of us with no elevation of soul learn the proper prayers. We learn how to regulate our actions in the prescribed manner. We learn to murmur the prescribed words. We learn to hold our hands out and to kneel and to rise and whatever else.

And we learn how to wait and we learn how to hope and we learn, finally, how to die.

Morgan Meis is the critic-at-large for The Smart Set (thesmartset.com). He has a PhD in Philosophy and has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. He won the Whiting Award in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. He can be reached at [email protected].