Continued from yesterday.

Jan Vallone: You say that joy is the knowledge of the possession of the Holy Spirit, but that it doesn’t mean that you are happy. If joy doesn’t feel like happiness, what does it feel like?

Jan Vallone: You say that joy is the knowledge of the possession of the Holy Spirit, but that it doesn’t mean that you are happy. If joy doesn’t feel like happiness, what does it feel like?

Fr. Raymond Shore: It’s a confidence, a sense of fulfillment of God’s promise that he’s always with us. If you read about Saint Maximilian Maria Kolbe—he was a Polish Franciscan friar sent to Auschwitz during World War II—you don’t get the sense that he despaired.

When some prisoners escaped from the camp, the SS picked ten men to starve to death in an underground bunker to deter further escape attempts. Kolbe volunteered to take the place of one of them. In the bunker, he celebrated Mass each day and sang hymns with the prisoners. He brought them great comfort. Even the guards talked about it.

After two weeks of starvation, only Kolbe was still alive. The SS were annoyed because he wasn’t dying the way he was supposed to. So they gave him an injection of carbolic acid, but he survived two more weeks.

These are moments when you’re not happy. I think Kolbe survived because he felt joy. Joy can’t be taken away from you because it’s internal. It comes from God. Paul asks what can separate us from the love of God. The answer is nothing—not wars, tribulations, or disasters—because all those things are external to us. When we are one with God, we have everlasting joy within.

JV: This is a bit abstract. How does an average person begin seeking union with God?

Fr. RS: Through prayer.

JV: Yes, you said that earlier, but I don’t understand prayer. It’s not that I don’t talk to God, because I do. But I don’t understand why, and I’m not sure I hear anything back.

Fr. RS: Do you listen?

JV: I think I do.

Fr. RS: Listening takes practice. You have to train yourself. You might start with the act of adoration, sitting there, listening to the little things in life. It’s very rare that a clap of thunder or a firestorm is the sign of God. C.S. Lewis said God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks to us in our conscience, and shouts in our pains. Pain is God’s megaphone.

You have to learn to hear and see signs. Very often we miss what we are supposed to hear and see because the answer or sign that’s given is not what we’re looking for.

JV: What’s an example of a sign?

Fr. RS: How do you know you’re called to be a priest or nun? There’s a not a certitude. There’s an inclination. The signs are things people say, the way things respond.

For example, in formation I had a vocational crisis and thought of leaving. So I prayed about it. But there was nothing that suggested I was unsuited for the priesthood. Instead, there were people who didn’t particularly like me who all of a sudden said things like, “You know, you’re going to be a good priest.” I think at the time I was actually looking for a reason to leave, but I couldn’t get over the fact that these people didn’t say, “You’re a terrible preacher and priest. Go, get out and do something you’re more suited for.”

JV: So, signs are things of this world?

Fr. RS: Very often. Because we are such physical creatures, we often doubt ourselves without worldly signs.

JV: Yes, I doubt myself. I have a fear of construing things as a signs from God, especially if it’s an inner feeling that I need to do something. I fear that I’m misconstruing my own personal desires and attributing them to God so I feel entitled to do what I want. That kind of behavior has been destructive throughout history. The people who blew up the World Trade Center believed God was calling them to do it. And there were people who egged them on and applauded their actions when it was done. Were these signs from God?

Fr. RS: Remember Christ wouldn’t even allow Peter to raise a sword in his defense. He told Peter to put away the sword and healed the ear of the soldier Peter wounded. He said those who live by the sword, die by the sword.

With signs, there has to be discernment. You have to ask whether what you’re doing is in keeping what the faith says, not just what you think the faith says or would like the faith to say. And that requires real study. You have to study scripture and the writings of the doctors of the church and not let yourself be formed just by CNN or FOX News or even certain others who practice the faith, although you do have to talk to people you trust who know the faith.

Then you have to test the conclusions you come to. Mother Teresa, for instance, felt called to serve Calcutta’s poor and continued to feel that way even though quite a few religious objected to her ideas.

She could have taken their rejection as signs. But she didn’t. Why? Because she had studied her faith and knew it advocated love for the poor. And not everyone rejected her proposal. She always had a spiritual director—her bishop—who supported her. There was someone.

This bishop didn’t say yay or nay. He gave her permission to experiment, and the experiment lasted almost fifty years. And there were difficult times, but also positive signs, moments of grace when something resonated, like her patient who said, “I lived my life as a pauper, but now die like a king!”

JV: Signs are the listening part. What about the speaking part? How do you speak to God?

Fr. RS: Well, there are many ways. It can be an informal conversation, or something more formal. We Dominicans, for example, pray the liturgy of the hours. We chant the psalms at different points of the day—up to six or seven, depending on the community—from dawn until we go to bed.

The liturgy of the hours is speaking and listening to what is said, a long tradition of prayer that comes out of Judaism. David and Solomon had long conversations with God that have become the psalms. Sometimes they are laments, sometimes they are prayers of sheer joy or happiness, and sometimes they express anger, sorrow, penitence, or petition.

JV: So what happens when you do this? Do prayers said so frequently ever seem mechanical, something you don’t even pay attention to?

Fr. RS: Sometimes. But mostly, over the days and years, you come to internalize the prayers—they become a part of you, so when you are praying, certain parts of the psalms will rise up and speak to you in a personal way. And then you meditate on what you hear.

When you first begin, it’s not like this. It’s hard, because you have to learn the tones you sing and when to respond. You can’t focus on the words. But then it becomes second nature, and you begin to hear.

Fr. Raymond Shore is the nom de plume of a Roman Catholic priest of the Dominican Order—The Order of Preachers—who prefers a low Internet profile.

Jan Vallone is the author of Pieces of Someday: One Woman’s Search for Meaning in Lawyering Family, Italy, Church, and a Tiny Jewish High School,which won the Reader Views Reviewers’ Choice Award. Her stories have appeared in The Seattle Times, Good Letters, Faith & Values in the Public Square, Catholic Digest, Guideposts Magazine, English Journal, Chicken Soup for the Soul, and Writing it Real. She lives and teaches writing in Seattle.

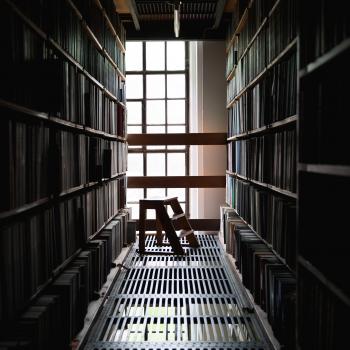

Photo above credited to Giovanna Carlotta Intra and used under a Creative Commons license.