You won’t want to do it, but I’ll ask just the same: imagine being twelve again.

You won’t want to do it, but I’ll ask just the same: imagine being twelve again.

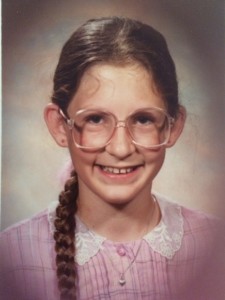

I was a mess: glasses, braces, and a wardrobe straight out of Little House on the Prairie. At five-foot-eight or so, I was not as skinny as a string bean but as a bean’s string.

Worse, I had just one friend that year, Rachel, so if she missed school, I had to eat lunch alone. On one of these occasions, a boy sauntered by, pointed at me, and sang, “Tania Po-o-o-ol-ner’s a lo-o-o-o-ner!”

I want to disappear, I thought. Also, that rhyme is a stretch.

What the other kids didn’t see beyond my awkwardness was my rich inner life. I didn’t see it either, of course. It was just the life I lived.

I played violin. I wrote stories, poems, and plays. I spent a lot of time alone in the backyard. And although I didn’t have many friends at school, I corresponded with pen pals, about fifty of them, from around the world.

Many years ago, I read somewhere (I’ve been searching for the quotation and source for months) that who we are at twelve—namely, the passions and skills we spend time developing‑—is the greatest predictor of our adult identity.

Perhaps I only dreamed this quotation, but I’ve been thinking about it ever since. After the age of twelve, I experimented. I made a short-lived foray into sports. I forsook my pen pals for more face-to-face communication. I taught myself flute.

In college, I convinced myself to major in elementary education for a semester or two. But I came back, fully back, to my twelve-year-old self.

Consider the fact that I’m a violinist and writer with a greenhouse. I conduct most of my communication through Facebook, my adult collection of pen pals. And after decades of contacts, I’m back to glasses again. The string bean thing, well, not so much.

Maybe it’s not all that surprising that most of us eventually come back to our childhoods. But without the encouragement I received in my preteen years, I don’t think I would have found the courage to stay twelve.

My parents weren’t all that involved with my activities. Sometimes their detachment hurt me, but it also helped me define myself outside of my their expectations, a luxury many children don’t have.

I think of Annie Dillard in An American Childhood, who discovers an amoeba under her microscope but can’t convince her parents to join in her excitement: “She [my mother] did not say, but I began to understand then, that you do what you do out of your private passion for the thing itself.”

Like Dillard’s parents, mine provided the means for exploration. They gave me the gift of weekly violin lessons, even when my dad went on strike. They supplied an endless stream of stamps for the half-dozen letters I wrote each day and a playhouse where I performed my scripts with paper puppets.

Without these resources to encourage my creative development, I would have glued myself to bad 1980s TV game shows and not discovered the riches of an artistic life. I realize not every child is this fortunate.

I write this with my daughter’s twelfth birthday just a few weeks away. Lydia is a strong student and a phenomenal trumpet player. But mostly, she is good at arguing. This is not a wink-wink, you-know-how-tweens-are statement. She is absolutely invigorated by conflict, anticipating responses and counter arguments several steps ahead, as in a game of chess.

She feels at home with persuasion, just as I felt at home writing letters and playing sonatas at that age.

As one who resists conflict at all costs, I find Lydia’s flourishing often quite difficult to live with. But I know that without the soul-splitting exercise of examining and defending truth, the world would be stuck in place. Injustices would have no end.

As a parent, the challenge is letting Lydia be who she is while providing appropriate boundaries for respectful behavior. One day, I’m sure, we will help by funding debate camp or contributing to her law school fund. But for now, we will watch this person grow into who she has already unfolded to be and pray that we make it out alive.

Perhaps you are a parent of a preadolescent, wondering just who has taken residence in your house. Who is this person at the root of it all, and how can you nourish those roots? Are you forcing piano lessons when all he wants to do is draw? Are you drilling for a spelling bee when her body wants to sprint through the woods?

How will you find the balance between providing experiences, teaching discipline, and allowing the child to be his or her mysterious self? My husband and I face these questions daily with no easy answers. I do know that adults who were forced to take on other selves in childhood eventually wilt like plants that have received shallow watering and scant light.

Even if you are not a parent, or at least not a parent of a child that age, you can shape the twelve-year-olds you encounter. Will you ignore them or roll your eyes at their noise and antics, as I am wont to do? Or will you take their words and passions to heart, attending their concerts, watching their games, and listening to the tales that issue from their pimpled faces?

I remember even passing criticisms and praises when I was this age more than words I received in high school or even college. During that phase of adolescent formation, while puzzling together my identity, I soaked up adult responses as truth.

The language arts teacher who read my work aloud in class to uproarious laughter taught me that art has the power to transcend social status. In fact, when I discovered that I could be both socially unpopular and successful as a writer, even as a comedic performer on stage, I did not despair. Rather, I reveled in language’s power to change reality and learned to covet the companionship of words most of all.

Twelve is hard and twelve is glorious, as promising and fragile as a carton of eggs. The world is full of these dozen-year-old wonders trying to become who they already are.

You won’t want to do it. I don’t want to do it. But let them take the lead.

Tania Runyan is the author of the poetry collections Second Sky (Cascade Poiema Series), A Thousand Vessels, Simple Weight, and Delicious Air, which was awarded Book of the Year by the Conference on Christianity and Literature in 2007. Her book How to Read a Poem, an instructional guide based on Billy Collins’s “Introduction to Poetry,” was recently released by T.S. Poetry Press. Her poems have appeared in many publications, including Poetry, Image, Books & Culture, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, The Christian Century, Atlanta Review, Indiana Review, and the anthology In a Fine Frenzy: Poets Respond to Shakespeare. Tania was awarded an NEA Literature Fellowship in 2011. She tutors high school students and edits for Every Day Poems and Relief.

Photo above belongs to Tania Runyan.