Much has been made of the fact Mark Driscoll was asked to stop passing out free copies of his new book when he made an impromptu appearance at John MacArthur’s Strange Fire conference last Friday. But that was merely a procedural matter. No one was allowed to hand out literature at the conference unless it had been pre-approved. A reasonable and understandable request to which Driscoll graciously acquiesced.

Much has been made of the fact Mark Driscoll was asked to stop passing out free copies of his new book when he made an impromptu appearance at John MacArthur’s Strange Fire conference last Friday. But that was merely a procedural matter. No one was allowed to hand out literature at the conference unless it had been pre-approved. A reasonable and understandable request to which Driscoll graciously acquiesced.

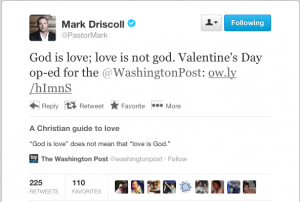

However, Driscoll’s comments in response to why he chose to hand out his book at the event is telling:

There’s one chapter on tribalism and how within evangelicalism, Christians have tended to form into tribes and then have arguments or debates with other tribes – often times talking about them, but not with them.

I think he accurately discerned the spirit of the conference: “Let’s bolster our tribe by bashing another.” The question is, why do evangelical Christians keep reverting to such primitive behavior?

Rene Girard’s mimetic theory of violence offers a simple answer: When a community is facing internal tension or external persecution–as Reformed Christianity most certainly is–one of the most effective ways to prevent self-destruction is for the community to redirect its hostility against a marginal individual or group. In other words, turn the potential war of all against all into a war of all against one–or most against some. Not only does this help reduce internal tension, it creates a strong sense of unity by purifying the group of dissenting voices and redefining the group’s identity over and against a common enemy.

Preferably, the target of the community’s scapegoating efforts should be an individual or group whose persecution will elicit no reprisals. The Charismatic movement fits the bill well, seeing as many people will agree with MacArthur’s critique of the movement’s excesses, at least in a general sense.

But for scapegoating to succeed, the crusade requires 100% unanimity. This is why in historical accounts of scapegoating (think of the story of Achan, for example, in Joshua 7), not only is the victim killed, so is his or her family. And the execution is often preceded by a confession, whereby even the victim admits to his or her guilt, whether or not it is factually true.

With this in mind, I think we can better appreciate the full power of Driscoll’s subtle protest of MacArthur’s conference. As one of the most influential Reformed leaders in America, by breaking the consensus MacArthur is trying to build, Driscoll almost guarantees the movement will wither on the vine. This is good news not only for the Charismatic movement but also for Reformed Christianity.

If people like Driscoll–whom I feature in Hellbound? laying out his own pretext for scapegoating re: the doctrine of hell–can see through such scapegoating efforts, that means the mechanism is failing, as Girard predicted it would. This leaves Reformed Christianity with two options: 1) consume itself with endless infighting while the movement slowly disintegrates, or 2) seek a new foundation for identity and unity that doesn’t require victimization or marginalization of others.

Judging from Driscoll’s comments, he’s actually advocating option number 2. Seeing as I regard Reformed Christianity as the epitome of sacrificial, scapegoating religion–and Driscoll as one of its most adamant proponents–I take this as a very positive sign.

Edit: As Kenton indicates below, a third option exists: Find a target upon which Driscoll and MacArthur can agree, which would reestablish unanimity. But I’m choosing to remain optimistic.