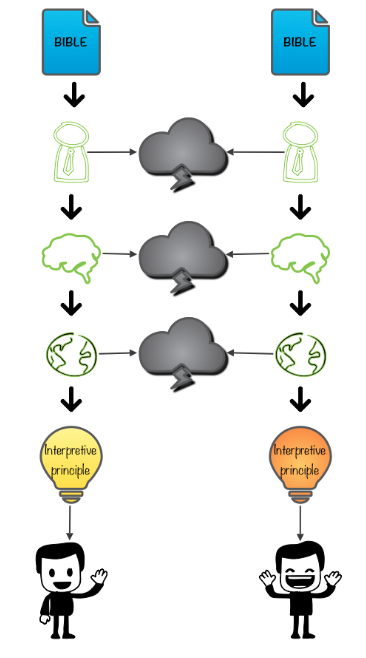

I ended last week’s post by explaining how when two people disagree on a particular Bible passage, we are often quick to interpret the disagreement as a clash between one person who is being faithful to the text and another person who is not. But what we are actually witnessing is a clash between two people who are applying different interpretive principles. That’s not to say both interpretive principles are equally valid. One could be informed by a better understanding of history, ancient languages, etc. However, if the disagreement is to be resolved, rather than dismiss the argument as symptomatic of some sort of moral, intellectual or spiritual defect on the part of the “other,” it’s far more helpful to accurately diagnose where the breakdown in communication is happening. The diagrams I’m providing in these blog posts are meant to help us do exactly that.

Here is the final diagram from last week’s post:

It takes things one step further to show that a clash between interpretive principles is often a clash between faith traditions, philosophical or theological arguments, experience or some or all of the above. This is already getting a bit complicated, but for the sake of simplicity, it also assumes a couple of things:

It takes things one step further to show that a clash between interpretive principles is often a clash between faith traditions, philosophical or theological arguments, experience or some or all of the above. This is already getting a bit complicated, but for the sake of simplicity, it also assumes a couple of things:

1) That we all view the Bible as the primary source of revelation

2) That the first place we turn after reading the Bible is to our particular faith tradition, and then we interpret Reason and Experience in light of that established body of beliefs.

However, as the diagram below illustrates, not all of us are wired that way.

If you’re part of the Catholic or Orthodox traditions, you see the Apostolic witness as the primary source of revelation. Out of this tradition comes the Bible, which, in turn, informs our philosophical and theological arguments and experience. Other faith traditions, which might be called Progressive, Liberal or even non-Christian traditions, view Experience and/or Reason as the primary source of revelation and interpret the Bible and Tradition in light of those. And as we have already illustrated, a typical Protestant position is to begin with the Bible and then interpret Tradition, Reason and Experience in light of the text. So once again, what appears to be a clash between interpretive principles is actually a disagreement on a much more fundamental level.

However, for the sake of simplicity, I am holding one variable constant–the Bible. But even those who agree on the primary source of revelation may not agree on how to arrange these secondary sources–in practice, if not in principle–as illustrated below:

Just because two people agree that Tradition is the primary source of revelation does not mean they agree the first place you should go when struggling with a Church teaching is to Scripture. Often the first thing we turn to is Experience. Either that or we encounter what appears to be a logical inconsistency and then apply Reason to help resolve the situation. So even though two people can agree on a fundamental level, they can be pulled apart by all sorts of secondary and tertiary arguments.

You can rearrange these variables in so many different ways it’s no wonder theological discussions often devolve into arguments, name-calling and excommunication.

In light of this, many of us wish for–and some of us think we have–a trump card to cut through all of the confusion. But as I hope you can see from the above, so-called trump cards merely amount to arguing for the supremacy of a particular configuration of variables. My faith tradition over your faith tradition. My arguments over your arguments. My experiences over your experiences. Ultimately, my interpretive principle over yours. But seeing as the system is entirely self-contained, no one’s interpretive principle automatically wins, because the best you can do is offer arguments in favor of your chosen configuration. There is absolutely nothing outside of the system that compels someone else to agree with you.

Now, someone has already asked where the Holy Spirit fits into this. One answer is to say the Holy Spirit is functioning to enlighten us on every level–through Scripture, Reason, Tradition and Experience. However, if that is the case, how do you explain the existence of 41,000 Christian denominations, never mind the millions of people who don’t consider the Christian tradition authoritative in any way?

A common answer is to attribute these disagreements to sin. People don’t agree or don’t believe, because many (most) of us really are ignorant, stupid, wicked and/or insane. Others take things a step further and argue that Satan and/or demons may be spiritually blinding us. Even if that were the case, the Holy Spirit should easily be able to compensate for such a condition, providing each of us with our own unique “road to Damascus” experience that helps us see things aright. But even if that happened–and most people’s testimonies contain accounts of similar experiences–our tendency is to make that experience the primary source of revelation. “I believe in Jesus because I’ve encountered him.” But from the diagrams above, you can see that doesn’t really solve anything. It merely rearranges the furniture, leaving all sorts of other arguments to work out.

For example, Joseph Smith, who founded the Mormon church, claimed to have had a rather fantastic series of experiences whereby the Book of Mormon was revealed to him on a series of gold plates. If you’re not a Mormon, you probably don’t accept his testimony as valid. But millions of fine, upstanding Mormons disagree with you.

So once again, even if we want to claim the Holy Spirit has led us to our position, we are back in the realm of the subjective. Who’s to say I should accept your experience as valid? Who’s to say you should accept mine? If everyone is claiming the Holy Spirit’s stamp of approval on their beliefs, we still have no idea how to figure out who is holding the trump card.

Another response is to say that the belief that the Holy Spirit will guide us into all truth is itself the product of a particular interpretive principle. Yes, verses in the Bible appear to make this promise. Yes, particular traditions hold to a literal interpretation of these passages. And yes, people have worked out complicated theological arguments for the inspiration of Scripture as well as ways in which Scripture illuminates the reader. However, other people don’t interpret these passages literally. And the existence of 41,000 denominations–an argument from experience–fouls up the works yet again. If the Holy Spirit is leading people into all truth, how come we can’t all agree on what that truth is? You might argue that the Holy Spirit is leading us all into different aspects of the truth which, taken collectively, illuminate the whole. I’d be willing to buy that. Except that some of the “truths” the Holy Spirit is apparently leading people into contradict other “truths” that people swear were revealed to them by the same Spirit.

So once again, the question arises–how do we resolve such disputes? Is resolution even possible? If so, what might that look like? We’ll save that discussion for my next post.