The Mystical Theology, attributed to Dionysius the Areopigate, is an important text in both the theological and spiritual traditions. In it, the author gives a highly condensed representation of his theological vision. In a series of posts, I will be examining the text, offering my own interpretative engagement with it, hopefully helping readers, both new and old, gain some greater understanding of where Dionysius’ theology can lead us in our engagement with God. To do this, I will first offer some brief comments on the author, then I will give a brief overview of the themes in The Mystical Theology. These first two posts will serve as an introduction to the text. Once the introduction is finished, I will slowly be going through the text, providing commentary based not only upon my own interpretation and understanding of the text, but also many previous commentaries as well.

The Mystical Theology, attributed to Dionysius the Areopigate, is an important text in both the theological and spiritual traditions. In it, the author gives a highly condensed representation of his theological vision. In a series of posts, I will be examining the text, offering my own interpretative engagement with it, hopefully helping readers, both new and old, gain some greater understanding of where Dionysius’ theology can lead us in our engagement with God. To do this, I will first offer some brief comments on the author, then I will give a brief overview of the themes in The Mystical Theology. These first two posts will serve as an introduction to the text. Once the introduction is finished, I will slowly be going through the text, providing commentary based not only upon my own interpretation and understanding of the text, but also many previous commentaries as well.

***

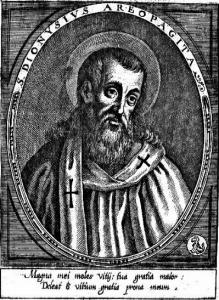

In the sixth century, the name of Dionysius the Areopigate appeared in the list of theological sources in a debate between bishops who supported the Council of Chalcedon and “Severians,” followers of Severus of Antioch (who was said to be a miaphyte, proclaiming that after the hypostatic union, there is only one incarnate nature to be found in Jesus Christ).[1] Among the sources the Severians used to defend their position were writings attributed to Dionysius the Areopigate. [2] The Chalcedonians, apparently unfamiliar with these texts, were confused, but because they had been introduced to them, they began to search for, read, and learn from his writings, with influential theologians such as John of Scythopolois and St. Maximus the Confessor working to bring Dionysius into the canon of authoritative theological resources.

Who the author of the texts attributed to Dionysius the Areopigate is not known. Some, with good reason, believe he was a Syrian monk, explaining how and why some of the earliest applications of his writings can be found in Syrian theological texts. Others suggest that he might have been a student at the Academy in Athens, perhaps as a pagan, perhaps as a Christian, before leaving Athens (perhaps, then, finding his way into Syria). There is no doubt that he had studied and knew the Greek philosophical tradition, with Proclus being one of the greatest discernable influences on his thought and writing. Perhaps he was a philosopher who later converted to the Christian faith; this would help explain some of the reasons why he named himself and acted in his writings as if he were the famous philosopher convert, Dionysius the Areopigate, who was converted by St Paul (cf. Acts 17:34).

What we do know is that he was a Christian writer with a great spiritual genius. Once his writings were read and studied, they were vindicated as authentic, and their early readers believed them to have been written by the Dionysius of the Book of Acts. This is not to say there was no objection to them. Questions abounded ever since they were first brought into the open, in part, because they were not known until such a late date. It was clear that there was a relationship between the views of Dionysius and Proclus. When it was assumed that Dionysius came first, it was believed that this meant Proclus borrowed from the Christians, but once historians discerned the way to read classical texts and engage critical analysis of them, more than enough evidence indicated that the author could not have lived in the first century, nor that he was likely to have lived before Proclus. He was indebted to Proclus, not Proclus to him. This has caused some to question the value of his writing because it seemed that Christians had been tricked by a pious fraud. However, that response assumes the author intended deception, which is not so clear, and also easily forms into an ad hominin criticism of the texts themselves, the value of which relies upon their content and not the person who wrote them.

It was quite common for ancients to write and think in the guise of others as a pedagogical exercise; our author might have begun his writing in that form, finding it freeing, and continued on, putting himself into the role of Dionysius and his friends in the roles of other Biblical figures, so that his writings could have been written with a kind of code which they all accepted, understanding their personal relationships with each other being echoed in the texts. If so, this was quickly lost to subsequent readers, but it might be possible to try to discern who these friends were, allowing is to possibly discover the author of our texts. Or, it is possible that Dionysius believed that there was a real and actual link between himself and the Biblical Areopigate, similar to what Hans Urs von Balthasar suggested saying that our Dionysius saw himself with a mission that united him with the Biblical Dionysius:

If one proves that he was not the convert and disciple of Paul, that he was not in correspondence with the Apostle John, nor with Titus or Polycarp, nor present at the death of Mary, that he did not send his writings to Timothy, nor experience in Egyptian Heliopolis the eclipse of the sun at Christ’s death, has one really done him the slightest injury? Is one telling this Syrian monk in 500 A.D. anything new, if one proves to him that he was not converted by the speech on the Areopagus in 50 A.D? Or does not the whole phenomenon exist on an utterly different level? On the level, that is, of the specifically Dionysian humility and mysticism which must and will utterly vanish as a person so that it lives purely as a divine task and the less the person be absorbed (as in the Dionysian hierarchies) in taxis and function, so that in this way the divine light, though ecclesially transmitted, is received and passed on as an immediately (amesôs) and transparently as possible? The identification of his task with a situation in space and time immediately next to John and Paul clearly corresponds for him to a necessity which, had he not heeded it, would have meant a rank insincerity and failure to respond to the truth.[3]

That is, the writer, who will also be named Dionysius in this study (instead of Pseudo-Dionysius), mystically saw himself united with and tasked with the mission of the Areopigate, a mission that came out of the first century but was manifested in his own work. An important part of his work is the conversion of the truths found in the pagan philosophical tradition to the Christian faith, employing it for theological and spiritual exploration. As Balthasar also indicated, this mission was not apologetic, but the explication of truth using the best human means possible to reflect upon the Christian faith.[4] This truth took the writer himself outside of himself and into the universal, transcendent, a-temporal truth which manifested itself to the world in the life and mission of Jesus Christ. Dionysius, our writer, like many contemplatives after him, found himself encountering that truth, experiencing it, finding his relationship to it was best represented in Scripture with the Areopigate. He found himself living and experiencing that truth in a trans-temporal, mystical fashion, so that he even felt as if lived through the events which he described in his works.[5]

It was not a pious fiction, but something else, something transcendent, a mission which could be seen started with the Areopigate and continued to be transmitted to the world. Dionysius, our Dionysius, found himself one with that mission. He was converted to the faith (whether or not he was born to a Christian family); his mind was formed in the Platonic tradition, with Proclus clearly his intellectual mentor (and, possibly, even more, if our Dionysius lived and wrote slightly earlier than assumed). He believed that tradition served as a great foundation by which the Christian faith and its transcendent truth could be presented, allowing others to follow after him and engage the transcendent revelation of God and experience the same experience he did. This, moreover, is why his works could be and were accepted; those theologians who came after and explored his writings saw they represented the truth of the Christian revelation, and did so in a way which preserved the full dignity of the Christian faith while recognizing the form in which it is presented will always be less than the truth which is pointed by it. Andrew Louth, therefore, was able to write about our Dionysius:

Denys the Areopagite, the Athenian convert, stands at the point where Christ and Plato meet. The pseudonym expressed the author’s belief that the truths that Plato grasped belong to Christ, and are not abandoned by embracing faith in Christ. Both Denys and Proclus were men of their time: just as Denys saw no anachronism in speaking with the voice of a first-century Christian, so Proclus saw no anachronism in counting his elaborate speculations no more than elucidations of Plato. What appears to us as a strange mongrel, the product of late Greek philosophy and a highly developed form of Christianity, appeared to Denys a pure-bred pedigree, or rather the original specimen of the species.[6]

The historical perspective of mystics differs from our empirical-historical perspective, because the mystics find themselves able to embrace the past in the present and unite themselves to it, while empirical understanding of history likes to keep all points in time and space distinct, incapable of over-lapping. Historically, our Dionysius cannot be the Areopigate; but mystically, spiritually, he found himself one with the Areopigate, not in a way which annihilated his own original personal character but in a way which found the two somehow able to be one and distinct. We can recognize our Dionysius taking this on, so that on the one hand, he was no simple pious fraud, but on the other hand, understand how and why that mission, seen true to the mission of the original Areopigate, allowed so many to see the two as being the one and same person and the confusion of the identity of our author created a misunderstanding of the historical-empirical relationship of the two.

Who, then, was Dionysius? He was a man with a mission, a man with a vision, a man with an experience, a man whose verification was found not in the identification of who he was but in what he said. He was possibly a monk, possibly a Syrian, possibly a former student at the Academy. He was a man touched by God; a man who could put to words his experience so that they can be validated by others who had similar such experiences as his.

He was also a man who left us a small collection of writings with some references to other works he claimed to have written. It is not clear if he wrote all he claimed, but if he did, then we only have a portion of his whole output. What we know he wrote was: The Divine Names, The Mystical Theology, The Celestial Hierarchy, The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, and ten Letters. Other works which he alluded to having written include: The Theological Outlines, On the Properties and Ranks of Angels, On the Soul, On Righteous and Divine Judgment, and his Symbolic Theology.[7] Balthasar believed them to have been written, especially because of the consistent way he addressed them in his extant writings, even as Balthasar believed references to writings written by others were not made up by Dionsyius, but existed, such as the texts he attributed to his teacher, Hierotheus.[8]

[Image=Dionysius the Areopigate [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Whether or not there was miscommunication going on between Chalcedonians, who taught there are two unconfused natures to be found joined together in one hypostatic person, with the non-Chalcedonians known as “monophysites” who taught one incarnate nature after the incarnation, is not our focus here. Nonetheless, those who study the matter make it clear that there were competing understandings of what was meant by the word nature (phusis) which caused confusion, making it difficult for all sides involved the Christological debates to reconcile with each other. When they appreciated this problem, they could and did, as can be seen in the way St. Cyril of Alexandria was able to agree with John of Antioch. It is likely that many so-called monophysites did not truly hold to what was condemned at Chalcedon and their objection was in the wording used at Chalcedon as well as how the wording was put into effect, while others, perhaps fewer than at first believed, truly believed in what was being objected by Chalcedon. Modern ecumenical dialogue between Catholics, Orthodox, and Non-Chalcedonian Orthodox, allows for and understands better how miscommunication works, leading them to look and discuss Christology in a better way. As a result, there have been many Christological agreements which acknowledges that all sides have a common core intention in their Christological expressions.

[2] See Pelikan’s introduction in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. Trans. Colm Luibheird. Intr. Jaroslav Pelikan, Jean LeClercq and Karlfried Froehlich (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 13 and William Riordan, Divine Light: The Theology of Denys the Areopigate (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2008), 23-4.

[3] Hans Urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics. Volume II: Studies in Theological Style: Clerical Styles. Trans. Andrew Louth, Francis McDonagh, and Brian McNeil C.R.V. (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1984), 148-9.

[4] See ibid., 149.

[5] It is not uncommon for mystics to have a similar experience, especially in regard to the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, feeling as if they were standing there, watching and seeing Christ’s execution.

[6] Andrew Louth, Denys the Areopagite (Wilton, CT: Morehouse-Barlow, 1989), 11.

[7] Ibid., 19.

[8] See Balthasar, Glory of the Lord II, 155-6.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook