Bede, in his History of the English Church and People, recorded Pope St. Gregory’s letter to Mellitus, explaining in part, the method of inculturation which St. Gregory suggested for the conversion of the English peoples:

Therefore, when by God’s help you reach our most reverend brother, Bishop Augustine, we wish you to inform him that we have been giving careful thought to the affairs of the English, and have come to the conclusion that the temples of idols among that people should on no account be destroyed. The idols are to be destroyed, but the temples themselves are to be aspersed with holy water, altars set up in them, and relics deposited there. For if these temples were well-built, they must be purified from the worship of demons and dedicated to the service of the true God. In this way, we hope that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may abandon their error and flocking more readily to their accustomed resorts, may come to know and adore the true God. And since they have a custom of sacrificing many oxen to demons, let some other solemnity by substituted in its place, such as a day of Dedication or the Festivals of the holy martyrs whose relics are enshrined there. On such occasions they might well construct shelters of boughs for themselves around the churches that were once temples, and celebrate the solemnity with devout feasting. They are no longer to sacrifice beasts to the Devil, but they may kill them for food to the praise of God, and give thanks to the Giver of all gifts for the plenty they enjoy. If the people are allowed some worldly pleasures in this way, they will more readily come to desire the joys of the spirit. For it is impossible to eradicate all errors from obstinate minds at one stroke, and whoever wishes to climb to a mountain top climbs gradually step by step, and not in one leap. It was in this way that the Lord revealed Himself to the Israelite people in Egypt, permitting the sacrifices formerly offered to the Devil to be offered thenceforth to Himself instead. [1]

There are many elements to St. Gregory wrote. First, he recognized that holy sites and places of pre-Christian peoples could be, and indeed, should be used by Christians. Moreover, he suggested that religious solemnities could be, and should be, introduced, which followed the days on which the non-Christians English people celebrated their religious rites. In both instances, Pope St. Gregory made it clear that there would be some element of purification going on; that is, those aspects of the older, pre-Christian faith which ran against the Christian practice or doctrine should be eliminated. Nonetheless, in their engagement with non-Christian practices and understanding of holiness and the divine, there was room for Christians to follow the examples of pre-Christian peoples and baptize them into the Christian faith. He also thought, because of the difficulty which might be involved with missionary work, an element of gradual transformation could be used, so that the people becoming converted to the Christian faith would slowly learn Christian teachings and moral expectations instead of being pushed for one giant leap into the faith which few, if any, would be able to make. St. Gregory indicated that this followed from the example God gave to us in Scripture, wherein we learn that the people of Israel slowly were motivated to discard the practices which ran contrary to God’s intentions for them (and the world).

St. Gregory was not the first to indicate that Christians could, and should, adapt what they have learned from non-Christian sources. Others can be found giving similar advice, believing that Christians should engage the truths they learned from non-Christian sources, finding ways to bring such truths into the fullness of the truth witnessed by the church. Origen, in his letter to St. Gregory the Wonderworker, suggested that the way Israelites took spoils from Egypt indicated that Christians should take the wealth of the traditions they came from and adapt them so that such truths could then be used to promote the Christian faith. Thus, he told St. Gregory the Wonderworker that training in philosophy (and all religious elements philosophy was thought to indicate in his time) could be used to help lead people to the Christian faith:

Thus, your natural good parts might make of you a finished Roman lawyer or a Greek philosopher, so to speak, of one of the schools in high reputation. But I am anxious that you should devote all the strength of your natural good parts to Christianity for your end; and in order to this, I wish to ask you to extract from the philosophy of the Greeks what may serve as a course of study or a preparation for Christianity, and from geometry and astronomy what will serve to explain the sacred Scriptures, in order that all that the sons of the philosophers are wont to say about geometry and music, grammar, rhetoric, and astronomy, as fellow-helpers to philosophy, we may say about philosophy itself, in relation to Christianity.[2]

When we study Christian history, we will often find Christians being encouraged to take what they can from non-Christians, to adapt and develop it, in order to help build up the church. If the church is the pillar and ground of the truth (cf. 1 Thes. 3:15), if Christ is the expectation of the nations (cf. Gen. 49:10), then we should expect the rays of truth found throughout the world. There is nothing to fear in engaging what is good and true in the world. The natural religious calling of humanity, even if it got subverted, contained much which is good and true, establishing cultural norms and ideals that can be and should be engaged by Christians. To do otherwise is to ignore the rays of truth shining throughout the world, indeed, to do otherwise is to suggest that God has not been at work with the whole of humanity but rather has been a respecter of persons and some groups, some communities, some cultures, have no relationship with him. Such an absurdity would lead Christian to deny not only God’s omnipresence, but his universal love for humanity. Now, to be sure, there are some Christians who have gone that far, and in doing so, turned God into some sort of monstrous image of their own inner desires, but the ideals expressed in Christianity, and in Judaism, are of a God who looks after and cares for the whole world because he is good and loves his creation.

Historically, Christian missions have been the most involved with the question of inculturation. Often, following what Pope St. Gregory suggested, missions were given all kinds of dispensations, allowing missionaries and their converts to be different from the norm. When in the West celibacy was normally expected of priests, sometimes married converts, especially those who were of a priestly class, were taken into the Christian priesthood (which is also why even today, some married Protestant ministers are allowed to become priests). It was recognized that it was more important to have loyal priests from among the people than it was to require a celibate priesthood, which was, after all, only a discipline. Likewise, as Christians engaged highly developed cultures, such as those found in China or India, realized that they had to adapt themselves to the social customs of the lands in order to create and establish an enculturated form of Christianity which borrowed much from the societies they entered. This is how and why St. Jean de Brébeuf could suggest that for missionaries in North America, they would have to learn the tongue and way of thinking of the people they engage, using it as Europeans might use St. Thomas Aquinas or Aristotle:

You may have been a famous professor or an outstanding theologian in France, but here you will be merely a student and – God be praised! – with what teachers! – women, little children, all the savages. You will be constantly exposed to their ridicule. The Huron language will be your Saint Thomas and your Aristotle, and – clever man that you are -, speaking glibly among learned and capable persons – you must make up your mind to be for quite some time mute in the company of these barbarians. It will be quite an achievement if, at the end of a considerable time, you begin to stammer even a little. [3]

Christians did not have to follow with the cultural patterns developed in Europe, though of course, there was great push-back to such inculturation and it took centuries for the Vatican to finally give the final approving stamp of the Chinese Rites. The lessons learned as a result of the Chinese Rites controversy was remembered by those who engaged missions, and so it has become normative to see the value of inculturation when engaging new peoples and trying to draw them into the Christian faith. Christianity does not have to be practiced with the same disciplines, the same exact same liturgical practices, all over the world: rather, all peoples have something to offer, and like what Nicholas of Cusa suggested in De Pace Fidei, they even have reason to develop particular rites to honor God in their own way. The unity of the faith is not lost if it is expressed in a variety of cultural form; rather, it is enhanced, as people are encouraged to find and worship God in a variety of ways and not just through some rote process which often becomes artificial. Thus Ad Gentes, the Vatican II document on missionary activity, explained that missionaries are to find and employ the seeds of truth, the seeds of the Logos, sown throughout the world, in the various cultural norms found in every society:

They should carefully consider how traditions of asceticism and contemplation, the needs of which have been sown by God in certain ancient cultures before the preaching of the Gospel, might be incorporated into the Christian life.[4]

The world, then, has always been guided by and inspired by God, who has sown seeds of truth in all cultures and societies, so that all cultures and societies can serve as ways to express and live out the Christian faith. Christians should not expect people around the world to ignore their own cultural norms; instead, the church is expected to find a way to express the Christian faith in and through the norms found in every culture. They have a place in the church and should not be derided or denigrated. No one should be told to conform to only one cultural expression of the faith. Thus, St. John Paul II, talking to the people of Asia, affirmed:

Wherever she is, the Church must sink her roots deeply into the spiritual and cultural soil of the country, assimilate all genuine values, enriching them also with the insights that she received from Jesus Christ, who is “the way and the truth and the life” (Jn. 14:6) for all humanity. [5]

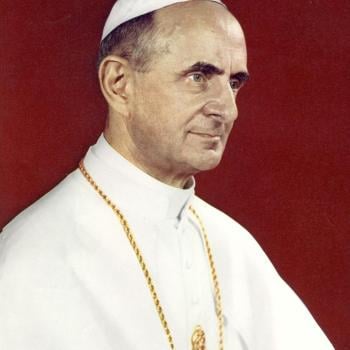

This is not true only for Asia; rather, it is true throughout the world. When Pope St. Paul VI discussed Christianity in Africa, he asserted that Christianity must accept what can come out of Africa, to accept an African form of Christianity which will differ from the way Christianity is practice in Europe. In doing so, the beauty, goodness of truth of what can be found in Africa and its cultures will be affirmed:

You may, and you must, have an African Christianity. Indeed, you possess human values and characteristic forms of culture which can rise up to perfection such as to find in Christianity, and for Christianity, a true superior fullness, and prove to be capable of a richness of expression all its own, and genuinely African. This may take time. It will require that your African soul become imbued to its depth with the secret charisms of Christianity, so that these charisms may overflow freely, in beauty and wisdom, in the true African manner. [6]

St. John Paul II agreed:

So with serenity and confidence and with profound openness toward the Universal Church, the bishops must carry on the task of inculturation of the Gospel for the good of each people, precisely so that Christ may be communicated to every man, women and child. In this process, cultures themselves must be uplifted, transformed and permeated by Christ’s original message of divine truth, without harming what is noble in them. Hence worthy African traditions are to be preserved. [7]

St. John Paul II brought this out in respect to the indigenous peoples throughout the world, including and especially those in the Americas:

Therefore, the Church encourages the indigenous peoples to maintain and promote with legitimate pride the culture of their peoples: their healthy traditions and customs, their own language and values. In defending your identity, you are not only exercising your right; you are also fulfilling your duty to hand on your culture to future generations, thus enriching the whole of society. [8]

In regards indigenous groups, he saw their respect for the earth, to “mother earth,” to be an important element of their spirituality which they should not only develop, but as an important element which Christians throughout the world should learn from them:

A central element of indigenous cultures is their attachment and nearness to mother earth. You love the land and want to keep in contact with nature. I join my voice to that of those who are asking for the adoption of strategies and means to protect and preserve nature, which God has created. Due respect for the environment must always be held above purely economic interests or the abusive exploitation of the resources of land and sea.[9]

As the world suffered as a result of the sinful exploitation and abuse of its natural goods, Christians must once again recognize the moral imperative to take care of the earth, to be stewards over it, indeed, to recognize their interdependent relation with it and its ecosystems. Indigenous peoples have not forgotten their relationship to the earth, and the way humanity can and does harm it through their actions, so they rightfully are called out and promoted for their cultural sensitivity to the needs of the earth. Thus, St. John Paul II said:

Concerning your proper place in the Church, I urge everyone to promote those pastoral initiatives which foster the indigenous communities’ greater integration and participation. For this, renewed effort will have to be made in whatever is related to the inculturation of the Gospel, since “a faith which does not become culture is a faith which has not been fully received, nor thoroughly thought through, nor faithfully lived.”[10]

The Amazon Synod of 2019 is an example of such a pastoral initiative, following the exhortation of St. John Paul II, and following traditional Christian understanding of the importance of inculturation as a way to engage the peoples of the world. While many critics try to decry the synod, because it does not follow European cultural norms, they themselves find themselves turning against what the church teaches should be the normative way to engage the nations of the world. There is an implicit racism coming from many of its critiques, as the indigenous peoples and their needs are being mocked by those who attack the Synod. It is true that throughout church history, there have been reactionaries and contrarians, like Tertullian, who in their rigor could not accept the church’s universal nature; but the success of its missions has always been a result of its willingness to adapt to the needs at hand. In missions, when there is the need for dispensations, the church has given them. The synod is looking to examine and come to terms with the ways the Christian faith can enculturate itself in the Amazon, as well as finding those economic initiatives, those dispensations which will be needed to help the Christian faithful. If they need priests, not just missionary priests, but priests coming from within, how are they to have them? If they need cultural expressions of the faith which will elevate their own cultural norms in Christ, what exactly will that look like? Prejudging the results by making particular European practices as binding norms will only strangle the spirit and lead to a greater dismissal of the faith. Only by embracing the long-developed understanding of missions, a hard-earned understanding which came out of the failures of the past, can Christianity truly take root around the world. Only by accepting the church is not and will not expect a legalistic approach to its norms will Christians be able to share their grace to the world. If it is determined that the faithful will receive better pastoral guidance with the elevation of various indigenous married men as priests, that does not even need to indicate any change in discipline but rather, the continuation of the church’s normative missionary engagement in the world (which, once again, explains a similar dispensation leading to various married Roman Catholic priests in North America and elsewhere). Likewise, if the church says missionaries and Christians need to heed the wisdom of the people of the Amazon, especially as they have much to tell us in regards to contemporary problems like climate change, this is as it should be, as this is how Christian missions have most effectively worked in its long and extensive history.

[1] Bede, A History of the English Church and People. Trans. Leo Sherley-Price. Revised trans. R. E. Latham (London: Penguin Books, 1968), 86-87. [Letter of Pope St. Gregory to Abbott Mellitus]

[2] Origen, “A Letter from Origen to Gregory” in ANF(4):393.

[3] St. Jean de Brébeuf, “Important Advice For Those Whom It Shall Please God To Call To New France, Especially To The Country of the Hurons,” in Francois Roustang, SJ., Jesuit Missionaries To North America. Trans. Sister M. Renelle, SSND (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006), 141.

[4] Ad Gentes in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 52.

[5] St. John Paul II, “Message to the People of Asia, Feb. 21, 1981,” in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 241.

[6] Pope St. Paul VI, “To the Symposium of African Bishops, July 31, 1969,” in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 162.

[7] St. John Paul II, “To the Bishops of Ghana, May 9, 1980” in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 231-2.

[8] St. John Paul II, “Message to the Indigenous Peoples of America, Oct. 12, 1992,” in Interreligious Dialogue: The Official Teachings of the Catholic Church (1963 – 1995). ed. Francesco Gioia (Boston: Pauline Books & Media, 1997), 495.

[9] St. John Paul II, “Message to the Indigenous Peoples of America, Oct. 12, 1992,”, 495.

[10] St. John Paul II, “Message to the Indigenous Peoples of America, Oct. 12, 1992,”, 496-7.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!