While the integral goodness of creation has been marred and hurt by sin, sin has not been able to have it completely destroyed. Creation is good by nature, and that goodness continues to be present to it in its continuing existence. So long as creation exists, that goodness can never be completely snuffed out. To be sure, creation is defiled by sin, with some elements having sin corrupt it more than others, but nonetheless, no matter how wounded it is, its inherent goodness cannot be entirely taken away from it. There is always some good which can then be taken up, embraced, indeed, reinforced, so that such a good can serve as the foundation by which that which was lost can be restored. For its original goodness to prevail, for sin not to have the final say, not only will sin have to be corrected, all that was hurt from sin will need some sort of healing grace applied to it, for if not, if there is not some sort of restoration of all things through grace, evil wins as it shows itself unable to be confronted and overcome by the good.

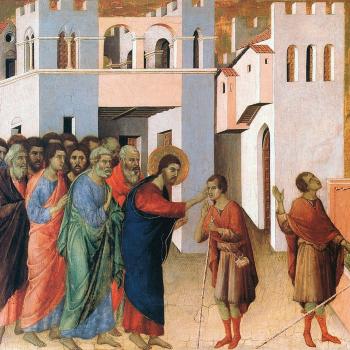

Sin seeks to destroy that good, and if it is left to its own, it will corrupt and destroy everything in its path until nothing is left. That is, if sin were allowed to come to its proper end, all of creation would be eaten away and destroyed, leaving behind an empty void. Not even sin or evil would exist since evil is not a substance, but a mere privation. Thankfully, God, in the incarnation, has come to the world to find all those who have gone astray, healing them from the harm they suffered thanks to sin so as to bring them back to their original, integral good. Then, once restored to their original goodness, they will be free to fulfill their original purpose, which is unity with God, that is, deification.

It is with this understanding we can find many, like St. Gregory of Nyssa, writing about the way God, in the incarnation, ends up restoring all things (apokatastasis). St. Gregory, for example, points out how Jesus’ parable of the lost sheep implies it: Jesus goes out to find all those who have strayed, those taken in and hurt by sin, going all the way to find the one which has gone the furthest astray so as to bring them back to where they belong:

When one sheep strayed from the heavenly way of life, evil drew our nature to an arid, uncultivated place; no longer does this number [one] pertain to the sheep which have not strayed but to the ninety-nine sheep. Vanity does not belong to the number of those who are included which is why “deficiency cannot be numbered.” Therefore Christ comes to seek and save the last sheep. He places it upon his shoulders, thereby restoring [apokatastesai] [the sheep] lost in the vanity of insubstantial things in order to make whole the number of God’s creation by saving the lost along with those who have not been destroyed. [1]

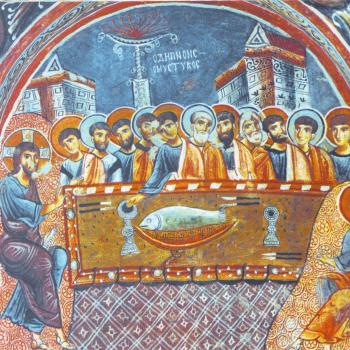

St. Gregory explains that God saves the last sheep, the one which has gone the furthest astray, pointing out that this as this done, that means the whole of creation, in some way, will be saved. Creation is one integral whole. If some element of it is lost, that is, destroyed for all eternity, then creation itself would be lost for eternity. Evil would be victorious. Jesus’ resurrection from the dead, however, shows us that sin, and the destruction it brings, will come to an end. Death reigns no more. Jesus has gone to the very edge of being, to find the “last sheep,” so as to be able to bring the last sheep back with him from the edge of destruction. If the last sheep is brought back in this manner, then every other sheep, every other things hurt or destroyed by sin will find itself likewise restored. On an objective level, if God is to be victorious in Christ, all things, including and especially the “last sheep,” will need to partake of Christ’s resurrection from the dead. This will lead to an objective restoration of all things, an apokatastasis in the eschaton, which is why St. Gregory of Nyssa connects the bodily resurrection, an objective act, with his belief that there will be some sort of the restoration of all things:

The soul existed right from the beginning; it has been purified in the past and will appear in the future. God fashioned the human body and will show the resurrection at the proper time, for that which comes after the resurrection was indeed fashioned first. The resurrection is nothing other than the restoration [apokatastasis] of all things to their original state. [2]

Objectively everything and everyone will be made whole: the eschatological resurrection will bring all the dead back to life. What we do not know will be the inner state or experience of everyone as a result of their objective restoration. It is within the subjective state that the possibility of some sort of “eternal perdition” lies. Eternal perdition must not be understood as an objective reality, an objective fact, as if some element of creation is denied its place in the restoration of all things, for that, once again, would mean creation would itself be lost for eternity.

If there is anyone who can be said to suffer from eternal perdition, which of course, we do not know, it would have to be in relation to their subjective response to their placement in the eschaton. It would have to be a state of being connected to and reflected by their will (and not just one particular act of sin). That is, they will have to perpetually resist and fight against their own good, and in doing so, constantly hurt themselves, causing themselves to needlessly suffer, which would create for them their own suffering. Just as everyone was given grace at their creation, giving them many goods, including existence itself, so everyone is given grace at their recreation, at the eschatological resurrection from the dead. How they will respond to that grace is not known. Will someone struggle and fight against it, with great pride and malice, angry that they cannot overcome their own objective reality, and in doing so, find themselves suffering as they fight against their own existence? Or will everyone eventually come to accept the grace given to them in light of the resurrection, embrace it, and open themselves to the divine life and all that God desires to shave of it with them? We might think, when someone sees and understands the good being offered to them, they will have no other response but accept it, and as such, believe that the objective restoration of all things will eventually lead to the subjective beatitude of all thing. That is, logically it would seem that no one will perpetually resist grace and so no one will suffer for all eternity. Such a line of thought is good, good enough to give us hope that such will be the case, but there are too many variables, too many factors which we do not know for us to give a proper conclusion. We can only speculate and find out if our hope is right when we find ourselves fully experiencing the kingdom of God for ourselves.

We should be humble and accept that we do not know what state everyone will find themselves in for eternity and so leave it as a possibility that someone might resist grace, even if doing so seems unfathomable to us, because Scripture presents that possibility to us. And if we look around us, we can see that, despite all sense of reason, many often resist doing what is in their best interest, which is why we cannot dismiss, however illogical, however surprising it might be, that someone might end up perpetually fighting against grace. On the other hand, as we do not know if this is the case, we should also accept it is possible, and hope it will end up being a reality, that no one will resist grace for eternity. This is why we should never trust in our own judgment of others when we try to discern what state of being they will find themselves in eternity. We are not to judge because we will never have what it takes to make a right eschatological judgment. Nonetheless, we can and should do all that we can to encourage people to be open to the greater good, to embrace it as much as they can in this life, so they will be ready for and open for it in the eschaton. The more people are trained to exercise their will in this fashion, the more likely our hope that everyone will subjectively experience the eschaton in beatitude can be realized.

[1] St. Gregory of Nyssa, Homilies on Ecclesiastes. Trans. Richard McCambly. Ed. John Litteral (Ashland, KY: Litteral’s Christian Library Publications, 2014), 31. [Homily 2].

[2] St. Gregory of Nyssa, Homilies on Ecclesiastes, 27. [Homily 1].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.