When we contemplate the eucharist, we can find all kinds of paradoxes associated with it, paradoxes which either can leave us in awe as we consider the implications behind them, or else, they can leave us wondering if we should continue to believe in the eucharist itself. The reason why there are two different responses is that some people easily accept the transcendent nature of truth, and understand they will not properly comprehend it, while others think the truth can only be found in what we understand, and if we can’t understand it, it can’t be the truth. So many of us have been led to look for simple explanations, and so, have not been given the tools to appreciate the value of paradoxes. Moreover, we tend towards materialistic explanations over metaphysical or spiritual ones, because we find ourselves more in tune with the physical world. Many of us even question if there is anything beyond the material world itself. Thus, we want physical explanations and answers for the questions which we might have, but when dealing with the eucharist, we find we are dealing with a teaching which requires acceptance of metaphysical principles, principles which deal with realities beyond the physical world. The teachings around the eucharist challenge us, and if we are unwilling to accept that challenge, if we are unwilling to consider metaphysical truths, we will, in the end, deny the eucharist.

Sadly, so many Christians are so caught up in the physical world they try to explain the eucharist in physical terms, and in doing so, get the teaching wrong. The eucharist brings us the real presence of Jesus, but that presence cannot properly be said to be a physical presence. Physically, we have bread and wine. So many, however, think, the bread and wine are mere illusions, that physically, we have flesh and blood, and if we but saw through the illusion, we would see that flesh and blood, and so they describe the eucharist in this fashion. Is it any surprise that this will offend many, as it appears to be outright cannibalism? But the reality of the eucharist, that it is Jesus, is a sacramental (spiritual) reality which is received through physical means, but that physical means is not of flesh and blood but of the species of bread and wine. It is not mere flesh which is being eaten, which is why partaking of the eucharist is not a form of cannibalism.

What is important for us is to understand that the eucharist is not merely some physical reality. It is a sacrament reality. It comes to us in a physical form, with the physical qualities (or accidents) of bread and wine. The reality is not the bread and wine, but Christ in his fullness, that is, in all that he is as a person. He is not divided into parts so that everyone can be given a small portion of him. Everyone everywhere receives the same, the fullness of Christ, even as together, what they receive is the same fullness, nothing more, nothing less:

Thus the whole Host is the body of Christ in such a way that each and every separate particle is the whole body of Christ. Three separate particles are not three bodies, but only one body. Nor do the particles themselves differ among each other as if they were a plurality, since the one particle is the whole of the body as the rest of them are that same body. [1]

The truth of the sacrament, the reality or the thing in itself of the eucharist, is not bound by physical laws; it is a transcendent spiritual reality. What is physical is found in particular locations and is easily divisible. Spiritual reality is not bound by such measures. While it might be difficult for us to understand how multiple people receive the exact same thing, and collectively, there is nothing more received, this is because of how we understand reality almost exclusively through physical laws. Even when we acknowledge that there is an ontological or metaphysical basis for that physicality, that is, a spiritual foundation from which physicality emerges, we are more attuned to the physical world, making it is the means by which we interpret reality. We rely upon abstraction to discuss the spiritual realm of being, using physical qualities which we know and understand as the foundation of those abstractions (as can be seen in the way we even talk about it as a realm of being). Nonetheless, we have ways to engage non-physical forms of reality without need for spatial considerations; this can be found, for example, is some of our engagements with mathematics, which is why mathematics was traditionally understood as a prerequisite for philosophical inquiry. Mathematics often shows us all kinds of paradoxes, helping us become acquainted with paradox and how it can help us apprehend the transcendent truth. Hopefully, we will be able to begin to understand how many things can share in or partake of one and the same thing without leading to any kind of multiplication of being going on. Once we can do this, we can then begin to see this in other ways, such as in the concept of humanity, where every person partakes of one and the same essence, each being fully human in themselves and yet combined together, do not establish several different humanities. Accepting this, we can then begin to engage the paradoxes connected with the eucharist because we can move beyond thinking of it as a mere physical reality which is understood in a quantified fashion.

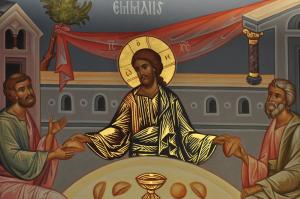

It is, of course, another paradox which is presented to us, when we consider what happened at the Last Supper. There, we find that Jesus can be said to have held himself in his hands:

For he held himself in his hands, and he fed his intimate friends with himself and so, as if inebriated by their sweetness and charity, has nothing of himself in which his most beloved will not share, as it is read that Joseph too, eating in the noonday heat with his brothers, was inebriated with them. [Gen 43.34] [2]

This can lead us to think about how Jesus is holding himself in his hands. The eucharist is all that he is, so that would include, what he is doing at the Last Supper. Thus, Jesus can be said to be holding himself holding himself in his hands. We can continue with this line of thought ad infinitum, where we have an infinite number of iterations of Jesus holding himself in his hands, giving us a rather strange paradox. On the other hand, everyone is holding themselves because they contain themselves in themselves. We do so in a limited fashion, while Jesus, as God, does so in an unlimited fashion. In this way, the paradox only reveals a truth about Jesus, that Jesus is unlimited, and no matter how you try to divide him, all you get is his fullness, a fullness which itself is not bound to physical laws, and indeed, is infinite it quality.

The reality of the sacrament of the eucharist is a transcendent spiritual reality. But it comes to us in a finite, concrete form. The physical form serves as a veil for the reality itself. We can apprehend that which is beyond us through that veiled form, and find, in doing so, we receive far more than we can ever comprehend. The veil, for the most part, remains for us; we perceive physical elements like bread and wine, and physically, our bodies act and react to them as they do to all physical things. But, behind the physicality is a reality which is brought with it, the reality of the sacrament, and by partaking of the sacrament, by being open to what is given, we find the reality of the sacrament is able to take root in us and transform us. The eucharist makes us one with Jesus, and through that, we find ourselves entering an ever greater paradox, the paradox that we are limited, contingent beings who nonetheless have a way to join in and partake of the infinite divine life itself:

For in this way the Father is shining in Christ the man in his humanity, through his consubstantial divinity with the Son. And so the Son shines in the Father, in the one and the same glorious shining substance of the divinity. And if Christ shines in us in this way, we are made one in the shining of the Father and of the Son in grace, which is the sign of the eternal shining in glory, by which we will shine through the in-pouring into us of the divinity of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. [Jn. 14.23] [3]

[1] Guitmund of Aversa “On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist” in Lanfranc of Canterbury: On the Body and Blood of the Lord and Guitmund of Aversa: On The Truth of the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist. Trans. Mark G. Vaillancourt (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2009), 104-5.

[2] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord. Trans. Sr. Albert Marie Surmanski, OP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2017), 51.

[3] St. Albert the Great, On the Body of the Lord, 67.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.