Christ teaches that humanity is called to be one, to share with each other their hopes and fears, their triumphs and troubles (cf. Jn. 17:21). Sin has divided us up, warring against each other with hate, while Christ, overcoming sin, works to bring us back together and realize our essential unity in and through love. When we resist this, we resist Christ, and so fall back into the pattern of hate and sin. This is why, throughout our lives, we must not only be reminded that Christ told us to love our neighbor, but also, we should keep in mind the example he gave of that love (the Good Samaritan). For, by listening to Christ and what he says about how we should treat our neighbor, we are given the exhortation we need to keep ourselves focused and stay on the path of salvation all the way to the end (where we find ourselves truly united with everyone and God in a great and glorious bond of love). When we seek to overcome both the temptation for sin, and the harm which sin has already caused us, we must never forget that he told us we should take care of and love our neighbor and that our salvation is found in our adhering to that love. When we are selfish and promote our own private good at the expense of our neighbor, giving ourselves excuse after excuse to do so, we fall back into sin, and risk finding ourselves bound to what happens to all that is connected with sin in the eschaton (that is, thrown into the lake of fire).

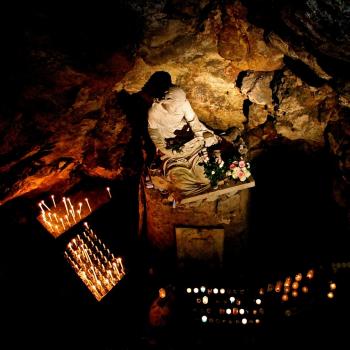

The struggle against sin must be a struggle against unlove; to purify ourselves from the stain of sin, we must purify ourselves from all selfishness and realize what it means to become one with everyone. Asceticism, therefore, is not to be seen as some sort of selfish abandonment of the world for the sake of personal spiritual gain. If an ascetic approached asceticism in such a manner, they might be able to do many remarkable things, things which will make them look very pious on the outside, but their discipline will fall very short from what God wants from them. This is why it was important for many spiritual elders to remind monks and nuns their duties to their neighbors:

The elders used to say that each one ought to assume responsibility for his neighbour’s situation; to suffer with him in everything, to rejoice and to weep with him. One should have the same sentiments as though wearing the same body and be afflicted as though one suffered affliction oneself, as it is written: “We are a single body in Christ” [Rom 12:5] and “The multitude of believers had but one heart and a single soul” [Acts 4:32].[1]

This is true, not just for monks and nuns, but for everyone. Our spiritual discipline will be deficient if we ignore our neighbor. We will not build ourselves up right because we will not be united with others, with the whole body of Christ. Often, spiritual elders remind us of this truth with paradoxical conventions. We must embrace love, not hate, but in a way, that can mean, we must hate hate, that is, we must hate sin:

One of the fathers said: “Unless you hate, you cannot love. If you hate sin, you do what is righteous, as it is written: ‘Turn away from evil and do the thing that is good’ [Ps 36:27]. But in all these things it is the intention that is required everywhere. Adam transgressed the commandment of God while he was in Paradise, while Job, sitting on the dunghill, maintained self-control. God only requires a good intention in a man and that he be ever in fear of him.”[2]

To understand paradoxes, we must look to and discern what it is they intend us not only to learn, but to do. The intention behind hating sin is to turn away from all sin, to turn away from the path of sin, the path of unlove, and therefore, to turn away from hate itself. The elder said we should hate sin to indicate that sin is something we should completely reject from the fullness of our being. The elder is using hate to fight against itself, to use hate to self-destruction, so that in the end, when we hate hate, we destroy hate, leaving only love in the aftermath (similar to the way Christ embraces death to destroy death from within). And, once we understand this, we can understand other similar paradoxes, such as the notion we should never tolerate intolerance. The key is the intention behind the words. The paradox comes from the apparent self-contradiction involved in what was said, and yet, that apparent self-contradiction is the point: we are expected to think and ponder, to look beyond mere words and grasp the greater truth which transcends them, to see how that greater truth will always be beyond what could be said.

When we are told to fear God, we must not allow such words make us think of God as some sort of powerful overlord who seeks every excuse to punish us, but rather, we should think of such fear to be the kind of fear people have when they are in awe of someone, when they love them and do not want to disappoint them because of that love. It is, in this way, another way to talk about the great, transcendent love we should have for God, but if we take words simply, if we have not broken through conventions by paradoxical riddles, we will likely misapply what is intended here.

We should approach the world in and through the lens of love, we should approach God in and through the lens of love, and therefore, we should approach spiritual wisdom with that lens, using it to help is interpret such wisdom and the paradoxes which are found in and with it. Love can and will embrace a kind of fear, the fear of disappointing the beloved, or, when talking about our relationship with our neighbor, it is the fear we have of causing them needless suffering. It will inform our intention, and will make us act accordingly, sometimes, doing things which will surprise others, such as when a monk is said to have sold off a copy of the Gospel so that the poor can be fed:

An elder said that one of the bothers possessed only a Gospel. This he sold and gave the proceeds to feed the poor, making this memorable statement: “I have sold the verse itself which says: ‘Sell what you have and give to the poor’ [Mt 19:21].”[3]

The monk saw the irony involved in the situation, but also, he saw how he executed it and in this way, he lived out the Gospel, even, perhaps, can be said to have truly acquired it, which is much more important than merely possessing a book, reading it, and not doing what is said in it. Let his understanding here inspire us as we consider what love should have us do for our neighbor. Let us hate hate so that we can truly have that love, and have it as the foundation of all that we should do.

[1] John Wortley, trans., The Anonymous Sayings Of The Desert Fathers: A Select Edition And Complete English Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 249 [N389/18.44].

[2] John Wortley, trans., The Anonymous Sayings Of The Desert Fathers: A Select Edition And Complete English Translation, 245[N378/11.125].

[3] John Wortley, trans., The Anonymous Sayings Of The Desert Fathers: A Select Edition And Complete English Translation, 251 [N392/6,6].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.