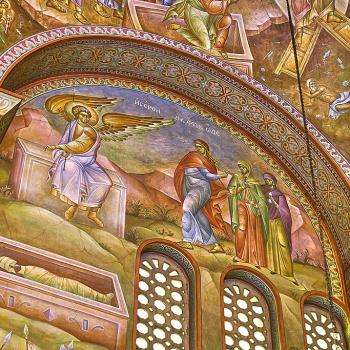

Christianity teaches the dignity of every human being. Everyone is made in the image and likeness of God. Historically, this has led Christians to promote the poor, the oppressed, social outcasts, indeed, those whose dignity have been unjustly trampled upon by society. This is why, in the earliest era of Christian history, we can see Christianity promoting a revolutionary understanding of women, one which gave them power and authority that had been denied them by society. Christianity made it clear that their voice, their testimony, was trustworthy. Women were often involved in the evangelical mission of the church. They did not need to be quiet. They did not even need to be married, or have a family of their own. Their worth was not determined by having children or a husband. They were seen as having the same worth of men, though to be sure, many women found that worth being challenged as the mores of secular society tried to and eventually were able to impose themselves upon the Christian community. Slowly but surely an extremely patriarchal approach took possession of the institution, and as a result, many ways in which Christianity promoted the dignity of women were circumvented, which is why, far from promoting the dignity of women throughout its history, Christianity also has a legacy which has undermined that dignity.

The sad fact of the matter is that while Christian teaching, and with it, Christian history, often promotes women, Christians have long struggled with that promotion and have found reasons or excuses to limit it. Even during Christ’s temporal ministry, many of his disciples had a difficult time accepting the way he engaged women, and after his ascension, those struggles became reflected in the debates found in Scripture. Some treated women as equals following Paul when he said in Christ, gender differentiations did not matter. Others challenged the implications of this, and so we find in the Pastoral Epistles (which are attributed to Paul, but which show signs they either were not written or otherwise further amended and changed by someone who was not Paul), women being told to know their place, to be silent and do what they have been told (especially by their husbands), finding their dignity and authority undermined.

We find both strains of thought being played out in the ante-Nicene era; we find women taking prominent roles in the church, with perhaps the most famous being St Thecla, and we see the resistance to this, where the teachings of the Pastoral Epistles are taken further, refined, and used to undermine the social development of earlier generations. It should not be surprising that, as a result of this conflict, many women, seeing the dignity which they had once been given was being undermined by many in positions of authority in the institutional church, would find themselves going to the peripheries, where that dignity was still being taken seriously, even if such peripheries were questionable concerning many other theological and social concerns. This is why, for example, Montanism could be and would be very appealing to women, as they were often given the authority and respect which was their due by those communities. This is something which has happened time and time again, sometimes with the peripheries being perfectly orthodox and leading to the creation of many saints, including many saintly women (such as happened with monasticism), sometimes finding themselves in a community which was orthodox but often questioned by ecclesial authorities (beguines), and sometimes leaving the institution and trying to find a new spiritual identity, one which did not deny them their proper dignity.

When the institutional church does not do as it should be doing, when it does not take seriously the dignity of women, but also, the dignity of those living in the peripheries, those who are poor, those who are oppressed by society, we should not be surprised people will lose interest in the institution and look elsewhere for their spiritual nourishment. The institution should not, of course, desire this to happen, and so it should always do better, to make sure that those within it receive its full support; it must especially make sure it does nothing which undermines human dignity. When it fails to do this, those within it must speak up, helping the institution reform from within.

While there was a continuous struggle within the institutional church to determine what roles women could and should have, they were, in general, being given more respect and authority in the church community than they were given by society at large. This is why, despite many of its failings, despite ways it showed itself incapable of discerning the implications of Paul’s relativizing the distinctions of genders in Christ, the institutional church could be seen at the forefront of women’s rights in the early Christian era. This is especially true in the way the church promoted women in ways which allowed them to be independent, to be able to live and thrive without marriage (or having children).

The Christian community helped those women who wanted to stay virgins and yet wanted their own independence. Society made it difficult, but when Constantine became emperor, one of the positive contributions he made was to overturn the rule of law which undermined the ability of women to be independent by allowing unmarried women the right to property:

Finally, the christian Emperor Constantine rescinded Augustan marriage laws and allowed every unmarried woman of twenty-five or more unlimited control of her own person and property. During the century that followed, many wealthy and influential women began to experiment with the ascetic life. They plunged wholeheartedly into the absorbing world of religious fellowship and controversy whose members sought to challenge and renew the old patterns of society. Their detractors called them mad. Their admirers called them ‘virile souls’, who had burst the confines of their own sex to fly unfettered to the very apex of the society of the City of God.[1]

This was revolutionary for Roman society. Sadly, as with many positive developments initiated by Constantine, the gain ended up being limited, indeed, temporary. For a time, we see the rise of independent, wealthy women in the church, women who became powerbrokers in society and in the church. St Jerome would never have been as influential or as successful as he was if he did not have such independent women backing him with their patronage, among which we find St. Paula of Rome (and her family) and St. Marcella of Rome. Many of his writings were made on their behalf. We should not ignore many other powerful women of the time, women like St. Melenia the Elder, who made her way to the Holy Land, formed her own religious community, and helped influence and shape the developing Christian community.

However, because many of these women used the resources they had to form religious communities, instead of staying in society as a whole, they did not accumulate more wealth, and as such, what they had diminished over time, until at last, there was nothing left. When that happened, the religious communities they formed, if they continued, would have to rely upon men as their benefactors, leading to changes in the community and the kind of influence and power they had. While women who helped shape a golden age of Christian spirituality and education, the benefactors of that age were men, as women slowly lost the power and independence they had been given. This is not to say all the advances Christianity made for women were lost, as it would be difficult to fully circumvent the revolutionary advances early Christianity made. But, over time, we will find those women who could best use those advances and promote them were those who had wealth and power, such as those in noble families (like St. Pulcheria), while ordinary women had their voices diminished (in a way far more than ordinary men did).

This is why, when Christians point to advances in the early Christian community, when they point to extraordinary women who died defending their rights (such as early virgin martyrs), and say Christianity is pro-women, they are telling half of the story. Christianity, can be, and should be, pro-women. However, often Christians have been fighting against the implications of what that means, and throughout history, for every advance made for women, we will find resistance by Christians, resistance which will either take away the advance, or at least extremely limit it, so that eventually, those advances themselves become forgotten and even questioned (as we can see happened with women deacons).

Christians need to reengage Christ and his promotion of women, to see how far they have fallen from that spirit, and to do that, they need to listen to women and their experiences more. They need to do more than be defensive, speaking of the ways in history Christianity have helped advance women’s rights; so long as they are focused on the best elements of the past while ignoring the way things are today, they are hindering women’s rights in the contemporary world.

[1] Jo Ann McNamara, “Muffled Voices: The Lives of Consecrated Women in the Fourth Century” in Distant Echoes: Medieval Religious Women. Volume One. ed. John A. Nichols and Lillian Thomas Shank (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 11.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.