Exploring faith, race, and Sudanese identities in Black History Month

By Guest Author Mariam Babiker, Ph.D.

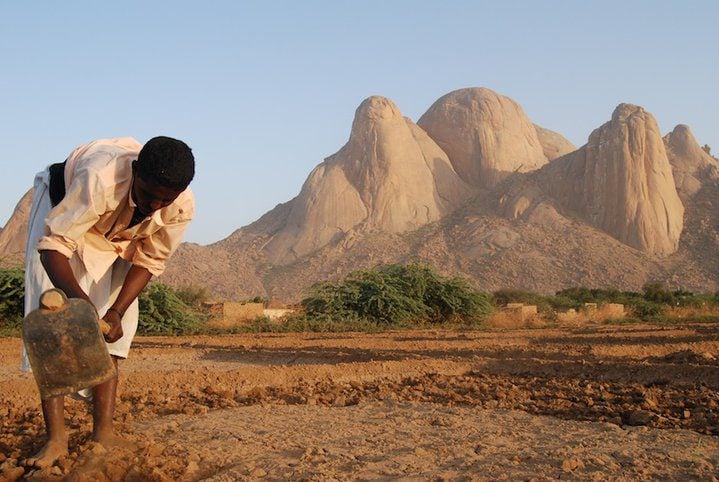

Growing up in Eastern Sudan, I was never really aware of my identity in respect to the larger diaspora of Sudan and the world as a whole. The perception of a Sudanese or black African identity is unique to those in the east. Historically, the word Sudanese is related to the concept of slavery and subjugation, and many of the elders of east Sudan did not link themselves to those labels and did not consider themselves ‘Sudanese’. This was possible because the east has its own Beja language and culture, and was seldom assimilated with other Sudanese tribes and peoples. On the other hand, people of eastern Sudan did not regard Arabs favorably either and perceived the Arabism of other tribes in Sudan as foreigners calling them “Balawiat“.

Growing up in such a climate, in addition to being female with very little interaction with the outside world, I never realized the disparity of these thoughts. I was proud of my eastern roots that placed me as a member of a deeply cultural tribe that speaks the Beja language. However, this belief was thrown into disarray when I started college in Khartoum, the capital city of Sudan. There I found that the ethnicity debate was much larger than me and that it was a constant conversation between students. Here everyone was proud of their own background and defined the social structure their own way. Coming from my background, I initially favored Arabs to other Africans due to the dominant exposure to Arabic language and the Islamic religion, and this bias increased with my study of the Arabic language, which I majored in. Throughout this time, I never considered or realized the contradiction between my Arab bias and my own dark African skin color!

The first and direct conflict I faced regarding my personal identity was when I went to North Africa. In Libya, the boundaries between Arabs and black Africans were clear to a large degree. To begin with, the Africans who were living there in large numbers all spoke English as their main language of communication, while the Arabs from Libya and Tunisia all spoke Arabic. In addition, there was the obvious disparity between the white skin color of the Arabs and the dark skin color of the Africans. These obvious differences clearly marked the divide in the society and the tiers each group belonged to, and many of the North African Arabs did not try to hide their arrogance over the black Africans. Perhaps they assumed this superiority because of the economic struggle faced by many Africans, which forced them to seek work with Arabs in order to earn a living, or perhaps to the historical engagement of black Africans to slavery and subjugation. It was at this time that I truly saw the difference between the two.

It’s ironic that at the time there was no choice in front of me and other Sudanese except to be classified as Africans because of our skin color. Although we speak Arabic, it was not enough to get Sudanese people out of this classification. What’s even funnier is that I was an Arabic language teacher in a high school in Libya, and many Libyans would still ask if I speak Arabic before starting a conversation with me! This was my experience in the land of the Arabs in North Africa, and when I came to the US back in 2000, I was again classified as an African because of my continent of origin, but this time it was in comparison to the white Caucasians of this country.

In my early days in the US, I was reluctant to mark myself as African American in official documents because I did not think I belonged to that category. However, I started to realize that the long struggle of African Americans for freedom and equality in the US resulted in pride of their identity, and whether I liked it or not I am part of that struggle. All these influences, from eastern Sudan, to the college days in Khartoum, and now Africanism in the US have all contributed to the construction of a stable identity that originated from a diverse and rich cultural source but has since added multiple influences. This has only served to make me more confident, self-aware, and appreciative of my experiences. I can also feel this development of my identity in the upbringing of my children, who are proud of their unique Sudanese identity that belongs to Africa, with Arab and American influences in harmony with no denial of any.

Mariam Babiker holds a Ph.D. in Education (Curricula & Methodology of Teaching) and a Master in Teaching Arabic to non-Arabic speakers. She is currently a Lecturer of Arabic Language in the department of Classics and Mediterranean Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Mariam Babiker holds a Ph.D. in Education (Curricula & Methodology of Teaching) and a Master in Teaching Arabic to non-Arabic speakers. She is currently a Lecturer of Arabic Language in the department of Classics and Mediterranean Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago.