It’s that time of year again. We’re once more officially allowed to sing about our Savior’s birth. I won’t dwell on how much I detest the divorcing of so-called “Christmas carols” from the rest of hymnody. I’ll just say that I believe we should preach the incarnation of the Word, both in season and out of season, using music along with every other method.

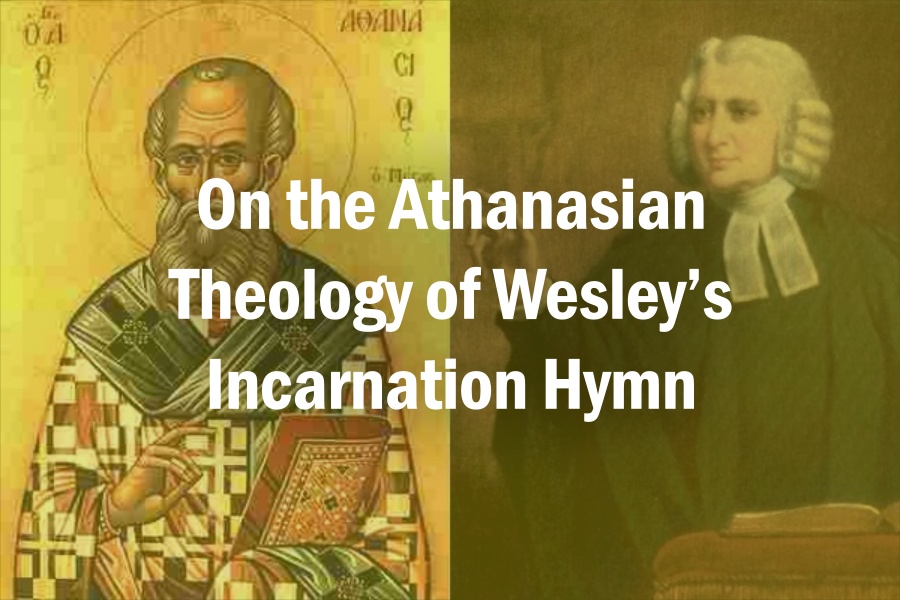

But for now, I’m going to focus on one of my favorite incarnation hymns, “Hark How All the Welkin Rings.” You may know it better as the abridged and modified “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing,” but I’m going to follow Charles Wesley’s full original lyrics. (Welkin, by the way, is an older word meaning the “sky” or “heaven.”)

In particular, I want to examine how Wesley captures an Athanasian understanding of the incarnation. It feels as if he had just finished reading Athanasius’ On the Incarnation of the Word of God, and used that as his inspiration to write “Welkin.” Of course I can’t say for sure whether Wesley intentionally followed Athanasius in this, but the parallel themes are unmistakable.

Here’s the full text of the hymn as Charles Wesley originally penned it:

Hark how all the welkin rings,

“Glory to the King of kings,

Peace on earth, and mercy mild,

God and sinners reconciled!”Joyful, all ye nations, rise,

Join the triumph of the skies;

Universal Nature, say,

“Christ the Lord is born to-day!”Christ, by highest heaven adored,

Christ, the everlasting Lord,

Late in time behold Him come,

Offspring of a virgin’s womb.Veil’d in flesh, the Godhead see,

Hail the’ Incarnate Deity!

Pleased as man with men to’ appear

Jesus, our Immanuel here!Hail the heavenly Prince of Peace!

Hail the Sun of Righteousness!

Light and life to all He brings,

Risen with healing in His wings.Mild He lays His glory by,

Born—that man no more may die,

Born—to raise the sons of earth,

Born—to give them second birth.Come, Desire of Nations, come,

Fix in us Thy humble home;

Rise, the woman’s conquering Seed,

Bruise in us the serpent’s head.Now display Thy saving power,

Ruin’d nature now restore;

Now in mystic union join

Thine to ours, and ours to Thine.Adam’s likeness, Lord, efface,

Stamp Thy image in its place;

Second Adam from above,

Reinstate us in Thy love.Let us Thee, though lost, regain,

Thee, the Life, the Inner Man:

O! to all Thyself impart,

Form’d in each believing heart.

The first thing I’d like to point out is that Wesley has the welkin announcing “God and sinners reconciled” at the very moment of the incarnation itself. Certainly, Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection mark the culmination of God’s reconciliatory activity, but the fundamental process of reconciliation began when God became man.

Why is this? The important phrase, “Universal Nature,” offers us a clue. George Whitefield seems to have been the first to remove this line (his Calvinism couldn’t allow it to remain), and most arrangements of the hymn since then have sadly followed suit. But the universal nature of humankind is fundamental to Athanasius’ understanding of how the incarnation could effect the restoration of humanity.

Here’s how Athanasius puts these thoughts:

Naturally also, through this union of the immortal Son of God with our human nature, all men were clothed with incorruption in the promise of the resurrection. For the solidarity of mankind is such that, by virtue of the Word’s indwelling in a single human body, the corruption which goes with death has lost its power over all. You know how it is when some great king enters a large city and dwells in one of its houses; because of his dwelling in that single house, the whole city is honored, and enemies and robbers cease to molest it. Even so is it with the King of all; He has come into our country and dwelt in one body amidst the many, and in consequence, the designs of the enemy against mankind have been foiled and the corruption of death, which formerly held them in its power, has simply ceased to be. For the human race would have perished utterly had not the Lord and Savior of all, the Son of God, come among us to put an end to death. (On the Incarnation, 9)

In his hymn, Wesley then describes Christ, “the everlasting Lord,” becoming a man, the “Offspring of a virgin’s womb.” In Jesus, we see the Godhead in flesh—the “Incarnate Deity.” But there is no claim that the Word was merely “Veil’d in flesh” (as some of Wesley’s detractors assert); Wesley makes it clear that Christ appeared as truly “man with men.”

Here’s what Athanasius has to say:

He, the Mighty One, the Artificer of all, Himself prepared this body in the virgin as a temple for Himself, and took it for His very own, as the instrument through which He was known and in which He dwelt. Thus, taking a body like our own, because all our bodies were liable to the corruption of death, He surrendered His body to death instead of all, and offered it to the Father. This He did out of sheer love for us, so that in His death all might die, and the law of death thereby be abolished because, having fulfilled in His body that for which it was appointed, it was thereafter voided of its power for men. This He did that He might turn again to incorruption men who had turned back to corruption, and make them alive through death by the appropriation of His body and by the grace of His resurrection. Thus He would make death to disappear from them as utterly as straw from fire. (On the Incarnation, 8)

Wesley describes Christ, having laid his glory by, being born so “that man no more may die” and “to raise the sons of earth,” “to give them second birth.”

Again, Athanasius:

The Word perceived that corruption could not be got rid of otherwise than through death; yet He Himself, as the Word, being immortal and the Father’s Son, was such as could not die. For this reason, therefore, He assumed a body capable of death, in order that it, through belonging to the Word Who is above all, might become in dying a sufficient exchange for all, and, itself remaining incorruptible through His indwelling, might thereafter put an end to corruption for all others as well, by the grace of the resurrection. It was by surrendering to death the body which He had taken, as an offering and sacrifice free from every stain, that He forthwith abolished death for His human brethren by the offering of the equivalent. For naturally, since the Word of God was above all, when He offered His own temple and bodily instrument as a substitute for the life of all, He fulfilled in death all that was required. (On the Incarnation, 9)

Wesley describes Christ displaying his “saving power” to restore our “ruin’d nature.”

Athanasius:

Much more, then, the Word of the All-Good father was not unmindful of the human race that He had called to be; but rather, by the offering of His own body He abolished the death which they had incurred, and corrected their neglect by His own teaching. Thus by His own power He restored the whole nature of man. (On the Incarnation, 10)

Wesley describes Christ, “in mystic union,” joining his nature with ours and our nature with his.

Athanasius:

He, indeed, assumed humanity that we might become God. He manifested Himself by means of a body in order that we might perceive the Mind of the unseen Father. He endured shame from men that we might inherit immortality. (On the Incarnation, 54)

Wesley describes Christ effacing Adam’s tarnished image, stamping his own image in its place, and thus reinstating us.

Athanasius:

You know what happens when a portrait that has been painted on a panel becomes obliterated through external stains. The artist does not throw away the pane, but the subject of the portrait has to come and sit for it again, and then the likeness is re-drawn on the same material. Even so it was with the All-Holy Son of God. He, the Image of the Father, came and dwelt in our midst, in order that He might renew mankind made after Himself…. (On the Incarnation, 14)

The Word of God came in His own Person, because it was He alone, the Image of the Father Who could recreate man made after the Image. (On the Incarnation, 13)

Finally, Wesley describes how our loss of union with Christ brought about our loss of life, but that we regain life when we regain Christ.

Athanasius:

God had not only made them out of nothing, but had also graciously bestowed on them His own life by the grace of the Word. Then, turning from eternal things to things corruptible, by counsel of the devil, they had become the cause of their own corruption in death; for, as I said before, though they were by nature subject to corruption, the grace of their union with the Word made them capable of escaping from the natural law, provided that they retained the beauty of innocence with which they were created. That is to say, the presence of the Word with them shielded them even from natural corruption. (On the Incarnation, 5)

As, then, the creatures whom He had created reasonable, like the Word, were in fact perishing, and such noble works were on the road to ruin, what then was God, being Good, to do? Was He to let corruption and death have their way with them? (On the Incarnation, 6)

For this purpose, then, the incorporeal and incorruptible and immaterial Word of God entered our world. In one sense, indeed, He was not far from it before, for no part of creation had ever been without Him Who, while ever abiding in union with the Father, yet fills all things that are. But now He entered the world in a new way, stooping to our level in His love and Self-revealing to us. (On the Incarnation, 8)

So next time you hear this beautiful hymn (even if you only hear it via an abridgment), stop to consider the powerful Athanasian theology Wesley presents. And most importantly, consider the incredible mystery of the incarnation—of our God who became a man, so that we might become God.

If you have not yet read Athanasius’ On the Incarnation of the Word of God, you really should check it out. It’s a surprisingly quick and easy read. There are plenty of free translations available online, or you can pick up the newer translation I’ve been quoting from (with an introduction by C.S. Lewis) for just a few bucks.