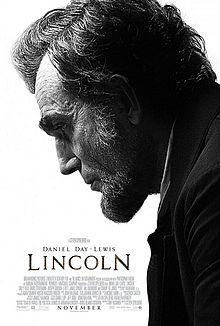

I’m eagerly anticipating seeing the new Lincoln film later this week, having been a huge fan of the man for many years. From all I’ve read and heard about the movie, it’s a splendid evocation of Lincoln and his era.

A number of years ago I gave a sermon about Lincoln, one that contains some information on an aspect of his life that I think is key to understanding him: his deep melancholy. I’ll blog again after I see the film, but in the meantime perhaps these comments might prove interesting for those of you who are also fans of the Man from Springfield (and if you want to read a wonderful book about this topic, get a copy of Joshua Wolf Shenk’s Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness):

You probably already know a quite a bit about Lincoln, but one aspect of his story may not be familiar to you. In particular, I want to tell you about a gift that Lincoln possessed, the gift of melancholy. Melancholy—which is related to what we would call depression—was both a blessing and a curse to Lincoln. I think the story of how he bore that affliction, and of how it deepened his character and faith, holds some lessons for us today.

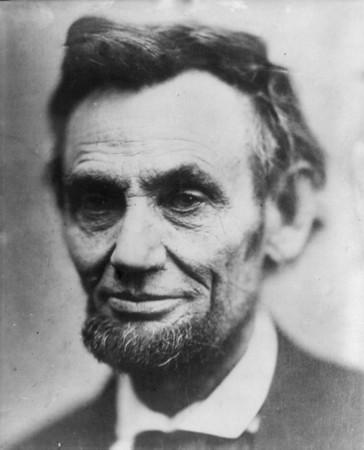

From a young age, Lincoln often experienced deep emotional pain. Part of it was the result of early losses, including the death of his mother when he was nine. But much of his melancholy seems to have been an inborn personality characteristic. Many of his contemporaries commented on the pervasive sadness that hung about him. Artist Francis Carpenter said of him, “I have [commented] repeatedly to friends that Mr. Lincoln had the saddest face I ever attempted to paint.” A fellow lawyer who knew Lincoln for many decades thought that “no element of Mr. Lincoln’s character was so marked, obvious, and ingrained as his mysterious and profound melancholy.”

Historians believe that Lincoln suffered at least two major episodes of depression. The first came in his 20s, the second in his early 30s. Both times, his friends feared that he might commit suicide. At one point Lincoln wrote in a letter to a friend, “I am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally distributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth.”

The question of how Lincoln’s religious faith helped him with his melancholy is a complicated one. By the standards of the day Lincoln was not a conventional Christian, though he was a lifelong student of scripture. When he was growing up, in fact, the Bible was one of the few books he owned. Lincoln memorized long passages from it, words that would later form the basis for some of his most eloquent speeches and writings. He wrestled with scripture throughout his entire life, questioning and pondering it and seeking within its pages answers to his troubles.

While Lincoln occasionally attended a Presbyterian church in Springfield, he never officially joined any church and was skeptical of much of the religious piety of his day. But as Lincoln suffered one loss after another, his religious faith underwent a transformation. One son died at the age of three. Another son died at the age of 11 when Lincoln was president. His marriage was troubled. Several close friends were killed in the Civil War. During his years in office he was criticized relentlessly in the press and by fellow political leaders, as many questioned his judgment and lack of political experience. And of course during the war there was the relentless drumbeat of casualties and deaths, on a scale unparalleled in American history.

So how did Lincoln bear it? How did a man who had already suffered two major depressions cope with such strain, surely the greatest that any president has had to bear? He bore it in part with humor—Lincoln was legendary for his wit and laugh—but mainly he bore it by turning inward and by meditating deeply on the ways of God. He rejected the easy platitudes of those on both the North and the South who said that God was clearly on their side in the war. He came to see the Civil War, in fact, as a penance for the sin of slavery, a penance that had to be borne by both the north and the south equally. Most of all, he came to believe that the ways of God were inscrutable, but that he himself had a role to play in the enactment of God’s divine plan.

Lincoln never ceased to suffer from that deep sadness that had haunted him from the time he was young. Most people would have been broken by what he had to endure, both in his personal life and in his public role. But somehow his lifetime of pain was transformed into humility, vision, and a deep charity of spirit. In the furnace of his suffering, the dross was consumed and what remained, finally, was a kind of transcendent wisdom.

Why should we care about the life of Abraham Lincoln today? One reason, I think, is that his story is a reminder that in our greatest weakness can also lie our greatest strength. Lincoln’s melancholy deepened and transformed him. His suffering was his teacher. Without it, he would not have been the great leader that he was.

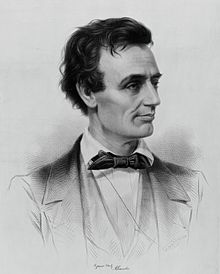

If you tour the Lincoln sites in Springfield, Illinois, you’ll see the high-tech, impressive new museum that tells the story of his life. But for me, the most moving part of my visit came in the Old State Capitol, the place where Lincoln delivered his famous “House Divided” speech and where he lay in state after his death. At the end of our tour of the building, the guide showed us two sets of photographs. The first set was of a young Lincoln and of his political rival Stephen Douglas, also as a young man. Douglas was handsome and debonair, Lincoln awkward and ungainly.

The guide then showed us pictures of the two men after the passage of three decades. Douglas’ face had hardened and grown colder. It was the face of a man who had spent his life pursuing power and influence. And then the guide held up a picture of Lincoln, taken just days before his death. Looking at that face, you can see in its deep lines the traces of so many deaths and so many sorrows. But Lincoln also radiates a hard-won peace. That face is a parable in itself, is it not?