Philip Jenkins (author of books that include The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity) is always worth reading. I’ve long admired his ability to distill complicated religious movements and themes in clear and insightful ways. In How To Read China on the website Real Clear Politics, he writes that knowing something about The I Ching, the ancient Chinese book blending philosophy and divination, is necessary to understand modern China. His piece raises interesting questions about our own built environments. What messages do we send through our homes, skyscrapers, and office parks?

Traditional Chinese religion and philosophy — and the two are impossible to separate — assumed a balance of forces. These forces could be strong, hot, active and masculine (yang) or weak, cold, passive and feminine (yin). Both are necessary to the workings of the universe, and neither is either good or evil of itself. The whole world can be defined in terms of shifting balances between forces, including the five geographical directions (north, south, east, west and here/center). Yang forces are strongest in the south, the realm of the sun and the color red, where summer heat and fire predominate; yin powers are cold, northerly and black. Each direction has its own variations of balance, its distinctive colors, elements, symbols and animals.

And that brings us to the The I Ching. Thousands of years ago, Chinese courts had a passionate interest in divination and fortune telling. Taking only one technique from a range of several, diviners cast yarrow sticks to determine shapes and patterns. These were organized initially in rows of three horizontal lines, trigrams, depending on whether they were solid (yang) or broken (yin). Three yang lines indicate Qián, Heaven; three yin lines symbolize Kun, Earth. There are eight possible combinations, which include such elements and features as Water, Wind, Fire and Mountain…

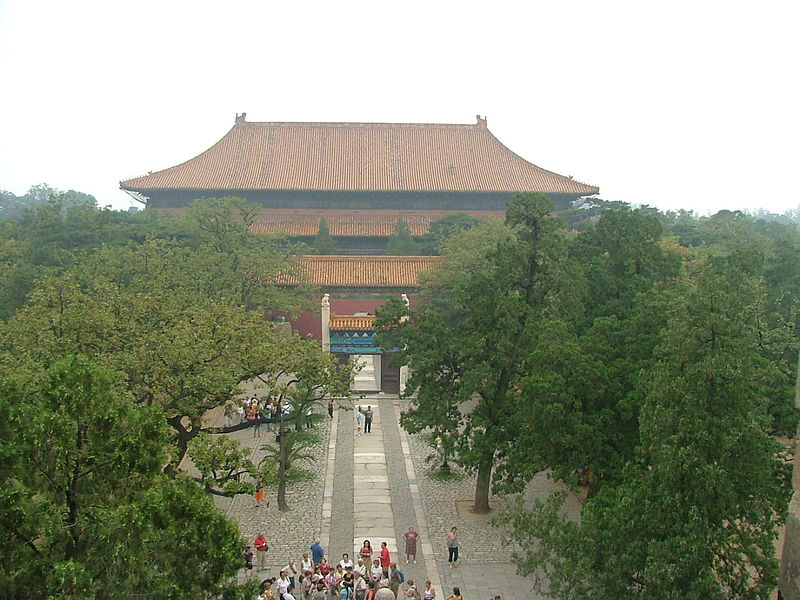

The crucial importance of these ideas becomes obvious when you visit any of China’s spectacular historic sites, such as the Imperial Palace or the Ming Tombs near Beijing. Everywhere, you see signs of that older world-view, in the colors of particular buildings or roofs, and especially in their directional alignments. The halls and residences of the Forbidden City are grouped in threes and sixes, reflecting the Heavenly trigrams and hexagrams.

You also see that I-Ching structure, with buildings displaying the characters and symbols of trigrams. Of course that particular structure is to the north, as it is a place of old age and death, just as that other building symbolizes the rising strength of the east. Who could have built it differently? Similar patterns underlie humbler buildings, and the outlines of whole cities and their street-plans. Nothing is left to chance.

With some awe, you soon realize that the whole built landscape — and over several thousand years, the human imprint on the Chinese landscape is very deep — is a legible text for those with the symbolic and visual literacy required to read it (emphasis mine). And although acquiring true expertise in these matters is a lifelong commitment, even recognizing that the text is there to be read vastly enhances your appreciation of the places. Conversely, if you don’t begin to see the symbols and the design, you are missing most of the story.

Making this kind of study even more valuable is that many mainland Chinese people are painfully conscious of having lost their connection with these ancient techniques. Quite apart from the impact of Westernization, the Communists struggled hard to uproot older religions (though they were happy to associate their own power with the ultimate strength of redness, and the yang forces)…Today, though, particularly among educated younger people, there is a real thirst for old learning, a desire to reconnect with Chinese history. That’s also true of people who would reject any formal interest in religion or spirituality. They really want to discuss these things, even with a scantily educated foreigner (although true scholars always wear their learning lightly, and display it allusively).

There’s a whole world there, just waiting to be read.