Today marks the beginning of Thanksgiving week here in the U.S. It’s hard to think of a more wonderful holiday, for the only things you need to do are eat a lot of delicious food and give thanks for your blessings.

I’ve been looking for something to post about gratitude and came across this article in the Atlantic, one that at first might seem like a bad fit: Jonathan Rauch’s The Real Roots of Midlife Crisis. But the more I reflect on it, the more I realize it’s quite appropriate for the holiday.

At the heart of the article is a conundrum: why is it that life satisfaction typically declines after the first couple of decades of adulthoood, bottoms out sometime during the 40s and early 50s, and then increases with age, often (though not always) reaching a higher level than in young adulthood? The pattern, which has been observed across many cultures, is called the Happiness U-curve.

Author Jonathan Rauch writes about his own adventures on the happiness rollercoaster. Despite enjoying considerable professional, personal and financial well-being while in his 40s, he was plagued by a sense of disappointment and frustration. He couldn’t help dwelling on his discontents, both real and imaginary, and tried to resign himself to the fact that he was unlikely ever to be much happier.

He writes: “[Then] as I moved into my early 50s, I hit some real setbacks. Both of my parents died, one of them after suffering a terrible illness while I watched helplessly. My job disappeared when the magazine I worked for was restructured. An entrepreneurial effort—to create a new online marketplace that would match journalists who had story ideas with editors looking for them—ran into problems. My shoulders, elbows, and knees all started aching. And yet the fog of disappointment and self-censure began to lift, at first almost imperceptibly, then more distinctly. By now, at 54, I feel as if I have emerged from a passage through something. But what? … Long ago, when I was 30 and he was 66, the late Donald Richie, the greatest writer I have known, told me: “Midlife crisis begins sometime in your 40s, when you look at your life and think, Is this all? And it ends about 10 years later, when you look at your life again and think, Actually, this is pretty good.” In my 50s, thinking back, his words strike me as exactly right. To no one’s surprise as much as my own, I have begun to feel again the sense of adventure that I recall from my 20s and 30s. I wake up thinking about the day ahead rather than the five decades past. Gratitude has returned.”

The rest of the article explores the reasons why Rauch’s experience is common. Many studies show that the peak of emotional life may not occur until well into our seventh decade or later. What typically happens is that people become more accepting of their limitations. As people age they realize their future is increasingly constrained, and so they set goals that are more realistic and easier to pursue. (Out: winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. In: finishing up that essay for the local newspaper.)

To me one of the most fascinating parts of the article is its description of the “science of wisdom.” Writes Rauch:

There is no evidence … that people get wiser as a result of aging per se (as opposed to learning from experience over time—also, of course, an element of wisdom). And there is no “wisdom organ” in the brain. Wisdom is an inherently multifarious trait, an emergent property of many other functions. . . But it does look likely that some elements of aging are conducive to wisdom, and to greater life satisfaction. In a 2012 paper evocatively titled “Don’t Look Back in Anger! Responsiveness to Missed Chances in Successful and Nonsuccessful Aging,” a group of German neuroscientists, using brain scans and other physical tests of mental and emotional activity, found that healthy older people (average age: 66) have “a reduced regret responsiveness” compared with younger people (average age: 25). That is, older people are less prone to feel unhappy about things they can’t change—an attitude consistent, of course, with ancient traditions that see stoicism and calm as part of wisdom. In fact, it is well established that older people’s brains react less strongly to negative stimuli than younger people’s brains do. “Young people just have more negative feelings,” Elaine Wethington, the Cornell professor, told me. Older brains may thus be less susceptible to the furies that buffet us earlier in life. Also, as Laura Carstensen, the Stanford psychologist, told me (summarizing a good deal of evidence), “Young people are miserable at regulating their emotions.” Years ago, my father made much the same point when I asked him why in his 50s he stopped having rages, which had shadowed his younger years and disrupted our family: “I realized I didn’t need to have five-dollar reactions to nickel provocations.”

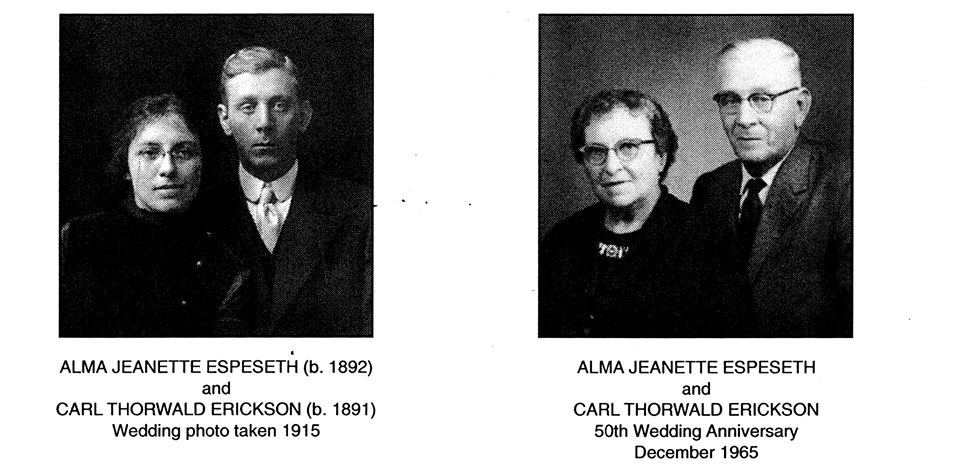

All of this brings to mind a family treasure that I discovered in my files not long ago: a 15-page transcript of an interview done by my Aunt Vernelle with my grandfather, Carl Erickson, when he was 82. In it he describes his hardscrabble life as an Iowa farmer with remarkable equanimity. My favorite line is this: “Oh, the first 25 years we was married it was really rough going. But after that it started to get better all the time.”

So here’s to riding the Happiness Curve into our future, surfing along the crest of midlife dissatisfaction until we can land on the Caribbean beach of our 50s, 60s, 70s, and beyond. It’s not that everything is perfect there—but the view is good, the pina coladas are delicious and the sand between our toes is warm.