As long-time readers of this blog know, I have a great devotion to the Virgin Mary. Raised as a Lutheran, I didn’t discover her until I was an adult, and even then it felt for a long time like there was something a little illicit in my fondness for her. Theologically speaking, she was from the wrong side of the tracks.

As long-time readers of this blog know, I have a great devotion to the Virgin Mary. Raised as a Lutheran, I didn’t discover her until I was an adult, and even then it felt for a long time like there was something a little illicit in my fondness for her. Theologically speaking, she was from the wrong side of the tracks.

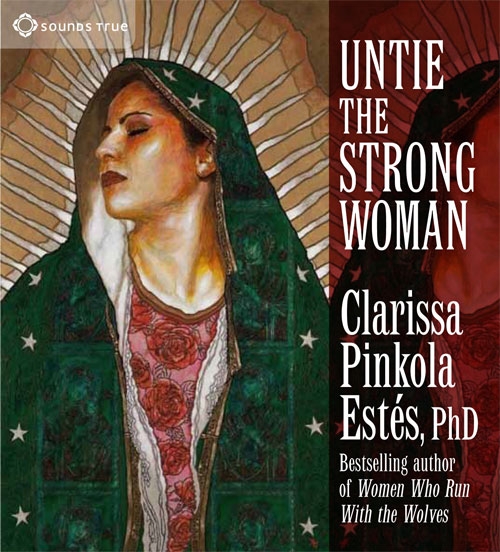

Thankfully I’ve left those prejudices behind, in part because Episcopalians are happy to welcome the Virgin Mary to the party. And thanks to my friend Darcy (whom I hope you know from her many perceptive comments on The Holy Rover), I discovered the most wonderful celebration of All-Things-Mary: Untie the Strong Woman: Blessed Mother’s Immaculate Love for the Wild Soul. Its author is Clarissa Pinkola Estes, who also wrote Women Who Run with the Wolves

. Estes is a Jungian psychoanalyst, poet, storyteller, and the most enthusiastic Mary fan I’ve ever come across.

One of the things I love about her book is that it dispels the notion that the Virgin Mary is a meek, mealy-mouthed figure who symbolizes the church’s subjugation of women. As its title suggests, Untie the Strong Woman celebrates all the ways in which Mary serves as a strong, passionate, and untamed protector of her children. “Holy Mother is not meant to be a fence,” writes Estes. “Holy Mother is a gate.”

Some of the most touching stories in the book are set in places of darkness. Estes writes of working with prisoners behind bars, of counseling deeply wounded and rebellious young women, and of trying to help the desperately poor. She turns conventional Mary imagery on its head with sayings like “Guadalupe is a girl gang leader in heaven.” She describes Latino folk practices like putting a shawl on statues of the Virgin Mary on Good Friday to console her on the death of her son. And she intersperses her stories and poems with beautiful collages, photographs and images of Mary in many different guises and forms.

“Her visits are not rare,” writes Estes. “They are common. No mother withholds herself from her children who cry out in need for her. A mother does not only aid ‘perfected’ children. Quite the contrary, she abides with those who stumble, bumble and suffer….This I can assure you from experience: no matter how deep an exile you have been forced to, no matter what the wound, no matter what disheveled condition your soul is in, no matter what you have done or not done–call and she will be there, as you best can comprehend her.”

There’s this lovely passage too: “Her fingerprints are all over me….Her palm prints are on my shoulders from trying to steer me in various proper and difficult directions.”

My favorite part of the book is Estes’ reflections on a prayer that many Roman Catholics know very well, but which was new to me. It’s known as the Memorare, which is Latin for remember, and it goes like this:

Remember, O most compassionate Virgin Mary, that never was it known that anyone who fled to your protection, implored your assistance, or sought your intercession, was left unaided. Inspired by this confidence, we fly unto you, O Virgin of Virgins, our Mother; to You, we come; before You, we kneel, sinful and sorrowful. O Mother of the Word Incarnate, despise not our petitions; but, in Your clemency and mercy, hear and answer them. Amen.

Writes Estes: “Memorare means Remember! Wake up! It is a command from the soul to remember who you are and what powers have been born into you; that you are the son, the daughter of Blessed Mother…You can hear it, if you cry the words of the Memorare aloud, that it is not ‘just a prayer’; it is an incantation, meaning it is literally meant to be sung out. There is a strong musical cadence to the Latin words, to any language the Memorare is translated into, a sound that is far more reminiscent of sandstorms, stirrups nodding, wooden saddles squeaking. It carries a rhythm that is far more reminiscent of the trot and the gallop, the sway of tent curtains, the sound of those fleeing, than of someone walking flatfooted in and out of buildings undisturbed. Thus, Memorare is a prayer for rough times, to one who knows rough times by heart.”

Thank you, Darcy, for introducing me to this book. It’s always good to spend time with Mary.