The 20th century philosopher Leo Strauss is perhaps best known for his reflections on “esotericism”, the practice by almost all pre-19th century authors to write their books on several levels, with a deeper level underlying the apparent, literal level.

As the title indicates, Strauss’s book Persecution and the Art of Writing focuses mostly on the fact that before the late-Modern era, there was no such thing as free-speech guarantees and that, since Socrates, most philosophers knew very well expressing too-unconventional ideas could put their lives in dangers.

But the book Philosophy Between the Lines by Arthur M. Melzer (good summary and review here by The Week‘s Damon Linker) not only makes an exhaustive and seemingly incontrovertible empirical argument that indeed esotericism was almost universally practiced until the 19th century, but also points to another version of it: what the author calls “pedagogical esotericism.”

Philosophers did not just practice esotericism as a way of sneaking subversive ideas past the censors, but also as a pedagogical device, much in the way of Socrates’ insistent questioning. For the Ancient philosophers, philosophy was not just, perhaps not even primarily, a body of doctrine, but an attitude of the mind towards contemplation and relentless questioning. The task of making philosophers, then, was not primarily about imparting ideas, but about leading people towards a certain state of mind. The philosopher wanted his pupils to discover his ideas on their own, by studying the text and working hard to get past the literal meaning, and thereby growing into a philosophic mind and posture.

In this regard, Melzer points out something else (in retrospect obvious, but which was quite an “Aha!” moment for me), which is the rarity of books in the era before the advent of the printing press, and the fact that the classical liberal arts curriculum included long study in “rhetoric” (i.e. the art of writing) which is something we have all-but forgotten. Everyone who was educated was trained in writing and reading between the lines. And because books were rare and expensive, owners of books, instead of the contemporary practice of reading a book once and then just moving on to the next, would typically reread the same book many times over their lifetime. Knowing this, authors would typically be alert to write in an esoteric style, concealing many layers of meaning into the text, so that the book would still be rewarding on the Nth reading. Just like, to the contrary, anyone writing a book today knows all-too-well that his book is competing with millions of other books, and so strives to make his argument as clear, literal and obvious as possible for fear that the reader just drop the book and move on to another.

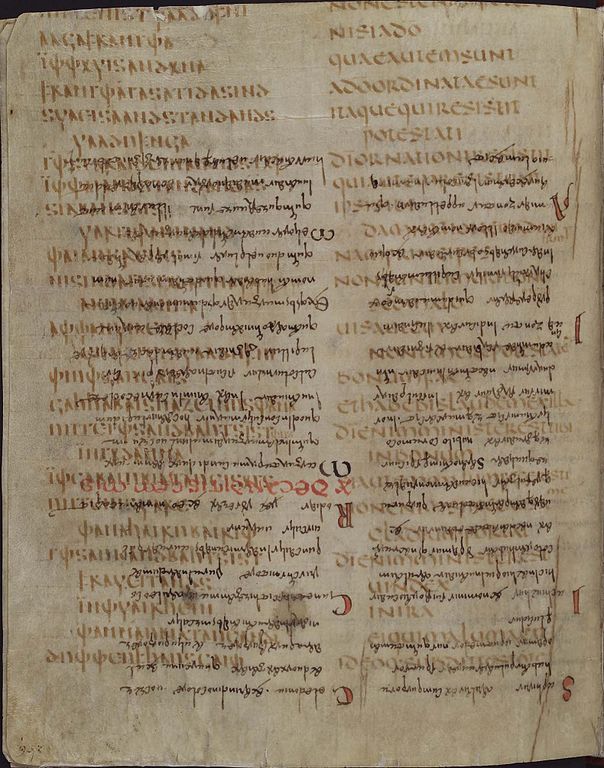

If this is how everyone understood the art of writing and the art of reading until very recently, then, certainly, this should have an impact on how we read the Bible. In fact, Strauss was first alerted to the reality of esoteric writing by his reading of Maimonides and Rashi, the two greatest Medieval rabbis. (Maimonides (like Aquinas) read Aristotle esoterically, as did every single Ancient commentator (Aristotle is the single author with the biggest secondary literature in the Ancient world), even though today Aristotle is considered as perhaps the most literal Ancient philosopher.)

Even without referring to inspired spiritual senses, we should still realize that the Modern prejudice that the surface meaning of a text is almost always the most authentic is just that–a culturally-contingent prejudice. By contrast, educated readers and writers for the rest of history would have had precisely the opposite assumption: that it’s more likely that the surface meaning of the text is not the most authentic. And this is indeed how many rabbis and Church Fathers read the Bible.

Food for thought.