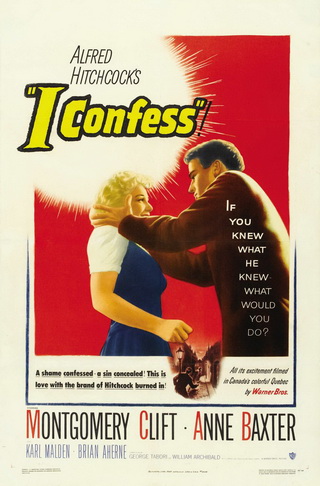

The boy and I stayed up late last night watching I Confess, long overdue and hands down one of the best movies I’ve ever seen. [Note, the wikipedia link includes the complete plot synopsis, so don’t read it until you’ve watched it.]

I had not watched the film sooner because I thought Hitchcock = Too Creepy for Me, but it was fine. Mature themes and violence, suspense in the many-plot-twists meaning of the term, but not a scary movie. Having just endured a dreadful 80’s-something BBC attempt at a period drama, this was a reminder that 1950’s stylistic flourishes are no hindrance to brilliant acting and direction. Excellent film. Excellent. Excellent. Have I mentioned, excellent?

It was timely viewing in light of the case in Louisana, in which a priest is being asked to disclose what transpired during a confession.

More Important than Life Itself

In the film, Father Logan is suspected of and eventually tried for murder. He knows who the real murderer is because the killer comes to him, openly, to confess the crime — and then turns around and frames the priest.

Following the “any moral means” rule of self-defense, the priest does try to acquit himself of the charges. He cannot, however, reveal the evidence that would clear his name because it is information acquired during a sacramental confession.

The clincher here, and there are a handful of equally terrifying situations which arise from time to time, is that self-preservation is not the highest good. We do have a right to defend ourselves, but not an absolute right.

This can confuse. Some legitimate means of self-defense, such as using lethal force to repel an attacker, resemble closely certain means strictly prohibited, such as using lethal force against an innocent person.

Here is my explanation of the principles of “double effect” vs. “doing evil that good may come of it”. The crux of the situation is that “doing the most good” is not the way we gauge the morality of an action. If I Confess were filmed today, there’d be sighing consolations about how Father really had no choice, breaking the seal is best for all, pat pat hug hug. No. The film is excellent because a man finds himself called to act heroically, and he acts heroically from start to finish.

Why is the Seal of the Confessional So Important?

We might just barely be able to understand why, for example, it is evil to kill an innocent person in order to save our own lives. Our modern sensibility rails against it, especially if that innocent is a marginal character compared to the beneficiary of the murder. Likewise, when murder is the apparent means to minimize suffering all-around, our cowardly culture demands death. If we stretch our minds, though, we can perhaps see in some situations why heroic suffering or death is better than murder.

But confession? Is it really worth dying for?

Yes. The same principle that animates the prohibition against murder is at work here, too, in a yet more powerful way.

We don’t commit evil that good might come of it because the good of our souls is more important than any earthly harm that might come to us. In the moral equivalent of rock-paper-scissors, soul always trumps body. The soul is what animates our bodies, here and in eternity. No sense attempting to enjoy the bodily resurrection if you haven’t got a heaven-bound soul for that glorified body.

So where does confession fit in? Confession is the sacrament that makes souls ready for eternal life. Deny a man confession and absolution, and you may well be consigning him to Hell.

Free Water, Just Pay Me $1 Million

Secrecy is the pledge that confession is safe.

Something I Confess does well is distinguish between secrecy and anonymity. Father Logan knows who the murderer is because the killer came to him openly, a personal friend asking for sacramental confession. To underscore the point, there’s a later scene, fleeting, where a little boy enters the church, gets Father’s attention, and the two go into the confessional. As much as anonymity can be an aid to confession in many regards, the guarantee of secrecy in no way depends on the priest not knowing who made the confession.

Anonymity cannot be guaranteed. I might go to a strange city, get in line, and confess through the screen to a priest I’ve never met. There’s a good chance my anonymity will be preserved. But as any lover of detective stories knows, there’s always that chance that Father will figure out exactly who-said-it. If I depend on anonymity to preserve the privacy of my confession, I’m like the criminal trying to keep all trace of the crime hidden — sooner or later, a clue will emerge that gives me away.

Anonymity can encourage sacramental confession, but secrecy is what saves souls. The certainty that the confession will be kept sacredly secret is what makes it possible for people to come forward for the sacrament. No matter what I say, no matter that Father knows exactly who is confessing, I can set aside the fears of the flesh and take care of my soul.

When one priest, even one single priest, violates the seal of the confessional, the whole sacrament is damaged. The whole church is harmed. Every single person on earth suddenly has a deterrent to seeking sacramental absolution.

It’s a serious matter. Deadly serious.

Image by Warner Bros., Inc.. Artists(s) not known. (http://www.impawards.com/1953/i_confess_ver2.html) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons