Please welcome guest blogger Timothy Scott Reeves. Scott is a philosophy student, father of six, and all around good guy. He’s Anglican in the CS Lewis and early-GKC tradition, and circulates comfortably in the meat-world orthocathosphere. I always find his comments insightful and was pleased when he offered to write a guest post for this blog. Enjoy!

Hashtags, Prayers, and Progressive Fundamentalists:

A Lesson from Sister Simone

What have fundamentalists to do with prayer? Everything…and nothing. They are the greatest examples of everything that prayer is not, which is precisely why we can learn a great deal about prayer from them. For instance, I owe the inspiration for this meditation on prayer to something I heard from the well-known fundamentalist Sister Simone Campbell of Nuns on the Bus fame. More specifically, while simultaneously mulling over her recent talk at the University of South Carolina Bernadine Lecture and the progressive media response to prayers for the San Bernardino attack, I came to the realization that the greatest threat from the fundamentalist heresy (especially its liberal progressive manifestation) lies in its effective subversion of prayer.

Admittedly, most readers familiar with the Nuns on the Bus will assume that I know nothing about Sister Simone Campbell…or perhaps wonder whether there are two nuns of that name whose identities I have conflated. Otherwise, how can I call her a ‘fundamentalist’?

The confusion is one of terms, not people. “Fundamentalist’ all too often gets reduced to a pejorative term used to dismiss people instead of addressing arguments. Frequently it means simply someone more religious than I am or someone who is violently religious or perhaps more specifically politically right-wing religious people. Obviously none of these apply to Sister Simone. Yet still I argue that she is a fundamentalist.

As a religion scholar and now a philosophy student I have given some serious consideration to what ‘fundamentalism’ actually means. If the term is to be useful at all, it cannot be merely an insult; it must have a technical meaning, or at least a describable family resemblance. So this, in brief, is how I have come to understand the term. ‘Fundamentalism’ is any post- enlightenment (modern or post-modern) approach to religion with the following three key points of family resemblance: Fundamentalists (1) despise tradition and are therefore (2) extremely narrow in their interpretation (avoiding the tension and paradox so common to the truth); finally (3) they reject the supernatural. Though these attributes are interrelated, it is the third point which I want to address most fully.

In what sense do they reject the miraculous? While the theological left and right of the fundamentalist heretics might fight each other to the death over whether the miraculous ever happened, neither of them want it to happen now. I would sum this point up by saying that ‘fundamentalism’ consists of a “form of godliness” while denying its power. Obviously they want power, but they prefer political power. They find influence and control in the worldliest sense quite amenable to their ‘godly’ ends, but the power of godliness is far too unwieldy to be safe and useful.

As for Sister Simone, she is unabashedly a modern religious. One can’t help but think she was influenced by those whom Schall has described in an old essay about Pope John Paul and liberation theology as “Guilt-ridden missionaries from the United States…advised to return home to preach the Latin revolutionary gospel [Marxist liberation theology].”[1] Nor can it be denied that she contradicts tradition freely in reference to same sex relationships and women’s ordination. Her passion for the poor is commendable, but it works as an interpretive construct always and only as the poor in relation to narrow socialistic ideologies. (She seems incapable of imagining anyone genuinely desiring to help the poor as legitimately concerned for them if they do not embrace the socialistic remedies she supports.) But the most grievous statement she made when I heard her goes to our focus here…she rejects the miraculous.

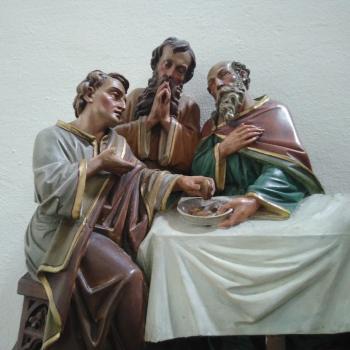

Sister Simone tells the story of the loaves and fish in a very tired, anti-miraculous, progressive fundamentalist way. “Why didn’t God count the women and children when reporting the miracle?” she asks. Well, it is because only the idiot men present thought Jesus did a miracle. All the women and children knew that in reality the moms had it all under control. The real ‘miracle’ is that everyone decided to share the food they brought. And for that—for teaching people to share—the whole lot wanted to forcefully make Jesus king? No. Yet because the miraculous too much embarrasses and challenges her modern bias she must narrow her interpretation to fit her secular fundamentalist religion. It is sad, really, to believe in a God one does not believe in. It leaves us in a position much like that of Ivan Karamazov and his Grand Inquisitor; we must aggressively work the halls of power for the sake of a revolution in order to correct the failure of Jesus and his earliest followers. We must come together to make the ‘miracles’ we so desire.

This is the fruit of fundamentalism, and its worst harvest is the death of prayer. For the ‘conservative’ fundamentalist prayer is talking to ourselves and telling ourselves things about God or perhaps a sort of worship of that rather distant God, because they believe all miracles ended with the apostles. Therefore prayer cannot be about answers and miracles. While framed slightly differently, prayer is just as powerless for the progressive fundamentalist for whom miracles never happened even with the apostles.

Consider the San Bernardino effect in the media. What was it so many complained about…even progressive ‘believers’? “Don’t give us your damn prayers,” was the general sentiment. “Do something useful. Pass our legislation about gun control.” The implication is of course that to pray is to do nothing. And it is equally as anti-miraculous and as fully fundamentalist as the Falwellian “everybody get your gun” response.

So what is prayer for our progressive fundamentalist friends? After all, they don’t always denounce prayer. We were to pray for Paris. Our President says to pray for persecuted Christians over Christmas. These were the mantras of progressive fundamentalists time and again. And in spite of what some have argued, it is not hypocrisy on their part—simply revealing. The response shows us what they think of prayer.

Just like prayer for the ‘conservative’ fundamentalist acts as little more than an encouraging word in a bad situation or a verbal celebration in good circumstances, so too with the progressive it behaves like a spiritual hashtag. Prayers, like hashtags, are what we use to share our emotions, to make ourselves feel better, when we can do little else. So prayers, like hashtags, are fine when we cannot help…or want others to think we cannot help. But when the cause ‘matters’ and ‘real’ action is called for, then prayers, like hashtags, are hollow.

This is precisely why I claim that fundamentalism is the most deadly modern heresy. It cuts us off from the living God while placating our emotional need for him. It makes us all fools, because the fool says in his heart, not always with his mouth, that there is no God. The fundamentalists, right and left, imply that there is no God of consequence, no present God…which is to say there is none, so we may control our own destiny and do what we think God should do.

I refuse to play the game—the politics of God game. Instead I will declare as fact with all the violence and offence of the Gospel message the truth that prayer is real communication with the one and only true and living God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ. And I will pray, not as a hashtag to God, but with all the conviction that it really matters, for prayer opens to us the power of godliness. Prayer partners with the God who will not be controlled.

T. Scott Reeves blogs at Scribe of the Kingdom.

[1] Schall, James V. “The American Press Views Puebla.” The Pope and Revolution. Ethics and Public Policy Center: Washington, DC. (1982). Pg. 87.

Photo by Ivar Leidus (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 ee], via Wikimedia Commons.