It will surprise no one that I have a few criticisms of Suzy Weiss’s report “Hurts So Good” over at Common Sense.

For those who haven’t read it, Weiss investigates the world of chronic illness social media, and makes a convincing case that there exists a genuine problem with aspects of that culture. I am going to accept at face value everything she does report, more on that in a second; where her journalism is sloppy, irresponsible, and shows profound ignorance of her topic is in what she doesn’t report.

First, let’s begin with what is good and valuable in her reporting.

Isolation and Social Media Vulnerability

Following the story of a young woman with serious symptoms that none of her doctors can properly diagnose, Weiss shows how this teenager’s problems have been compounded by her efforts to find support on the internet. She describes chronic-illness discussion forums where the prevailing fixation seems to be on staying sick.

Have I ever, in my decade or so of dealing with dysautonomia, been part of such a group? No I have not.

I’ve gleaned extremely useful information from a handful of disease-specific forums, and I have had several close friendships, both online and in regular life, with people whose ability to relate and understand has been a source of tremendous encouragement when life with an erratically-disabling illness gets overwhelming.

I’ve also benefited immensely from information dished out by the health-and-fitness world, because working towards peak performance takes much the same discipline and know-how regardless of whether you are training for a triathlon or just feel that way if you attempt a normal workday.

And that, I believe, is an essential distinction: My online chronic-illness support circles are people who are doing everything they can to get as close to “normal” as they can, despite the stark reality that “normal” will take Olympic-levels of focus and self-denial, and we the hopefuls are just as unlikely to get on the platform as every other athletic wannabe.

Still, we persist.

Nonetheless, I believe Weiss when she reports on these other, radically different social circles, which have sabotaged this particular young woman’s mental and physical health. The reality is that having an illness that is difficult to diagnose and difficult to treat is harshly isolating. Being unable to compete with “normal” is crushing on the self esteem, and teenagers are extremely vulnerable to that.

The simple fact of having such an illness is the equivalent, for a teenager, to being the target of a concerted bullying campaign* — except that all too often, the bullies are your own physicians (and they bully themselves just as badly).

It is not surprising under these circumstances that a teenager would seek affirmation wherever she can find it. It is important for parents to know that not all online communities are creating emotionally-healthy environments, and at times the dysfunction can be downright harmful.

Journalists Need to Tell the Whole Story

Unfortunately, Weiss’s report doesn’t provide adequate context. She (rightly) gives a fair bit of press to the “functional illness” theory of validating and treating inexplicable patient symptoms, for example, but doesn’t mention the vast number of now diagnosable and treatable illnesses that were previously believed to be psychosomatic or stress-induced.

Nor does she mention the appalling legacy of neglecting the differences between male and female bodies in the world of medical research, which means that even today many doctors don’t know about how women and men present differently for certain illnesses, and no one can yet adequately explain certain significant differences between how men and women experience disease.

Both of these realities have a direct impact on the experience of young women who present with difficult-to-diagnose symptoms.

Bad Reporting Undermines Good Medicine

The failure to tell the whole story wrecks Weiss’s credibility. Instead of being a believable source about a potentially very serious social phenomenon, she comes across as just another naysayer in the “quit whining, whiner” school of medicine. This has serious consequences.

Parents who have watched their daughters (and sometimes their sons) be gaslighted by doctors convinced of their own omniscience know that their child’s symptoms are frequently dismissed as “anxiety” or “hypochondria.” Trying to support a teen or young adult who is dealing with disabling but difficult-to-diagnose symptoms is often a fulltime job in itself. Parents in this position work furiously to find ways to shore up their child’s mental and physical health.

Weak reporting sabotages those efforts.

Some parents will be sucked into the picture Weiss has painted of hypochondriacs vying for attention and belonging, and thus they will begin, or continue, on a dangerous path of failing-to-treat. This not only risks their child’s physical health but also destroys the trust in the parent-child relationship.

Others will do the opposite, concluding that Weiss is just another member of Team Gaslighting and therefore ignore the potential hazards of assuming all online support groups are equally supportive.

As we have seen time and again throughout the pandemic, incomplete and slanted medical reporting wrecks the credibility of the medical profession. Unfortunately, Common Sense has fallen into that trap.

*Scroll down the page to see the videos. Please. You can watch it for free, just click to play; registration is only required if you want to earn continuing education credits for the course. Watch the first of the three videos. Patient’s talk begins at about the 12:00 minute mark; the slides just prior are right on point for this discussion. You have to turn up the volume during the patient’s talk, because you’re watching a video-of-a-video. (I haven’t watched the remaining two segments yet, so no idea what’s in them.)

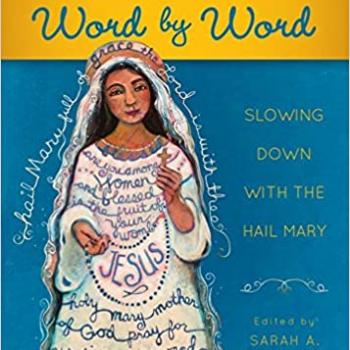

Photo: Girl sleeping on a “fainting couch” circa 1873, public domain.