I like to think of my soul as a shiny thing; a beacon of divine essence, a tiny portion of Godself that the Creator poured into me, one tiny aspect of all that is sacred and holy, walking around on the earth. But my embodiment is not drenched with that divine stuff — no. Rather, that holy essence is encased in the mystery of skin and bone and psyche, pushed into the deepest recesses, where all my own divinity — after all, it says right there in Genesis I’m created in God’s image — is hidden and obscured behind this thing that makes me human. This bone that holds me up, this blood that gives my life its pulse, this skin that makes me white.

I am just back from two week-long intensive classes, the latter of which was on the Black Liberation theology of James Cone. It’s a theology that is not meant for me — Black Power has nothing to do with white people aside from seeking liberation from us and our oppressive ways. But there is truth there for us — truth that can point us to our own disfigurement, the way our bright and shiny souls have somehow been mangled and twisted into an evil wretchedness that manifests itself as racial supremacy. James Cone, Black Power, and Black Liberation theology can offer us a new kind of freedom — the liberative power of truth telling.

Scripture tells us a story of a last supper that Jesus had with his disciples, at which he makes a disturbing announcement — one of his beloved disciples is going to betray him. Judas Iscariot, who had been with him from the start, had conspired against him, and the result for Jesus is nothing short of the cross — a public lynching and a shameful way to die. In the tenderness of intimate betrayal, Jesus says that one of his beloveds will turn against him. The story paints a poignant scene as each of the disciples ask, “Surely, not I?” Judas asks this, too — Not I, Rabbi? — knowing full well that he is, indeed, the one who will betray Jesus. Judas is practicing this not-knowing, this unwillingness to see, and Jesus responds with heartbreaking truth: Yes, Judas. You.

It’s easy to hate on Judas for this disgusting betrayal. But what I think we often miss by casting Judas right into the field of blood without a second thought is his brokenness, and the pain that existed between him and his friend, his brother, Jesus. It’s messy and complicated and can lead to very bad things, this relationship stuff. At its most benign, it’s hurt feelings. At its worst — at our worst — it’s crosses and lynching trees. The point is, the one who is broken here is Judas, not Jesus.

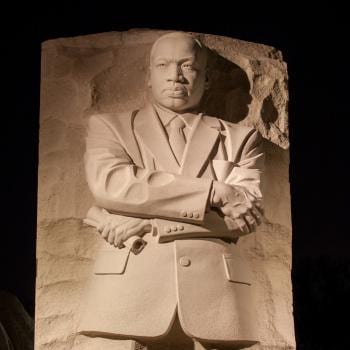

In his theological work, James Cone compares the cross to the lynching tree, illuminating both America’s horror and hypocrisy, our practiced not-knowing when the bodies are hanging right there for us to see (or, as the case may be these days, lying in the blood-filled streets). There can be no denying that America holds in her body a deep, painful fracture — a distortion of our collective soul, a disfigurement of the ideologies we claim to hold dear, but have never actually fulfilled. In his book, The Cross and The Lynching Tree, Cone says,

The cross can heal and hurt; it can be empowering and liberating but also enslaving and oppressive. There is no one way in which the cross can be interpreted. I offer my reflections because I believe that the cross placed alongside the lynching tree can help us to see Jesus in America in a new light, and thereby empower people who claim to follow him to take a stand against white supremacy and every kind of injustice. (The Cross and The Lynching Tree, Introduction)

White, Christian America has used the cross to both oppress black people — telling them their suffering will bring some great reward in some long-term, heavenly realm — and to maintain our own disfigurement, by protecting the structures that oppress. Because here is the thing: although our life may be far more comfortable, and we enjoy prosperity and relative safety and comfort that our black brethren do not (fight me on this — go ahead) the truth is that no oppressor is actually free. We are, instead, imprisoned by our own need to maintain that status quo that empowers us, captive to our own lust for control and the fear of losing it. This leads us right to our own Golgotha, where we are willing to pound nails through flesh and bone in a desperate attempt to keep what we have and what we think belongs to us: the right to public space, the right to consider our way the “normal” way, the false sense of supremacy and this strange idea that our white skin makes us more god-like — as if God has skin at all. Though our outsides and all their trappings might look glossed and shiny like souls, inside, our actual souls are held hostage. No one is free until we are all free.

Not I, Rabbi?

Like Jesus was with Judas, Black Theology is truthful about white betrayal. It looks us in the eye and tells us like it is; like Jesus on the cross, it points our attention directly to our own betrayal. In the great family of humanity, the construct of whiteness — this twisted identity that has been assigned to some of us based on weird, arbitrary things like melanin and hair texture — has distorted the true nature of our divine souls. The cross — and the lynching tree — are horrific measures that can point us back to ourselves, if we are willing to stop our practice of not-knowing and be brave enough to look at what we have done.

This practice of white not-knowing is evident in our everyday response to people of color and their expressions of rage, hurt, pain and injustice. Every eye roll and sigh of impatience with the Take a Knee Movement is a refusal to see. Every claim of “But Black on Black crime!” is the practice of not-knowing. Every time we bellow inconvenience over a protest or prioritize our own comfort and enjoyment over cries of injustice or claim that “he just should have followed instructions and then he wouldn’t have gotten shot,” we participate in a betrayal of Jesus and twist our own psyches into an even more painful disfigurement, moving us further away from what is, indeed, our divine essence. Cone says,

The passive acceptance of injustice is not the way of human beings. If eschatology means that one believes that God is totally uninvolved in the suffering of men because he is preparing them for another world, then Black Theology is not eschatological. Black Theology is an earthy theology! It is not concerned with the “last things” but with the “white thing.” Black Theology like Black Power believes that the self-determination of black people must be emphasized at all costs, recognizing that there is only one question about reality for blacks: What must we do about white racism? (Black Theology and Black Power, chapter 5)

This is a pertinent question for white people as well: What must we do about white racism? Which side of the cross do we wish to be on — which side are we on now?

If what Cone says is true, then the passive acceptance of black oppression by white people is an abdication of our own humanity. By refusing to see, with our practiced not-knowing, the suffering of lynched bodies, shot bodies, imprisoned bodies we are indeed the “white thing” with which Black Theology is most concerned. We are the oppressor. We are the nails and the hammer and the Roman soldier casting lots. We are Rome.

Surely, not me, Jesus?

If we are to call Jesus Rabbi and Lord, however, if we are to eat his bread and drink his wine, then we must share in the suffering of his afflicted body, in the pain of his identity as the child of God. We are called to emulate the embodied Jesus — the one who loved people with blood and guts; the one who reached out and touched people and let people touch him; the one who opened his heart, baring it to the sword and the whip. We have to love the world like Christ loved the world, and if you don’t realize that what he was after was justice, then I’m pretty sure you’re reading the wrong Bible.

As white people, this side of the cross is our Rome, our alignment with oppression. But just there on the other side? If we’re willing to listen to the theology of Cone, if we’re willing to be called out and up the hill to the lynching tree and actually look, there on the other side of that horrific human thing is resurrection. I don’t fully know what resurrection actually means, but I think it has something to do with untwisting my soul so I can see not just my own humanity, but that of other people, too. I think resurrection has to do with seeing Black Power and knowing that when Black people are free, we are too. It’s seeing Black Girl Magic and knowing that when she finds her power, I lose a few of my own chains. Her power is not mine to give — it’s hers to find. When I can stop pretending anything different, when I can just let her find it and know it has nothing to do with me, that’s Jesus looking into my eyes and saying, “Yes, you too. And I forgive you.”

__________________________________________________________________________________

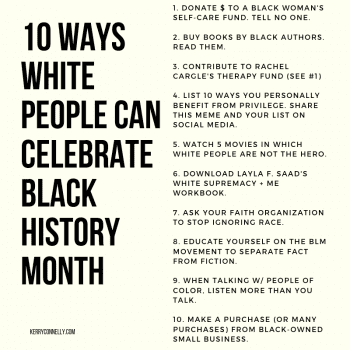

If you’d like to dig in to more of Cone’s theology as it might apply to white liberation from the sickness of racism, follow me on Instagram @kerry.connelly, where I’ll be posting a quote from Cone every day for the next two weeks, and discussing how it can apply to whiteness. Join the discussion!