I remember the room was gloomy, dark and overly warm; the speaker, monotone.

I sat next to my father, both of us uncomfortable and awkward in the middle of all that truth and reality, ours and everyone else’s, the looking at things the way they are. The man at the front of the room had a white board we could barely see in the darkly lit space — I still can’t remember why the lights were turned out. He had drawn circles all over the pale expanse as he doled out his dismal prognosis. He was talking about holes.

Our holes.

Yesterday, I was in Barnes and Noble with my son, itching to buy another book, knowing full well this is an addiction I should stop feeding. I have plenty of books at home, plus a Kindle for when I need that instant hit. But something about the scent of a book store, the ink and the paper and the creative force of all those words — it sucks me in every time.

Anyway. I was in Barnes and Noble with great aspirations to go and finally fill my eye glass subscription up on the second level of the mall when I suddenly started feeling sick. Instantly I knew that all I wanted was to fall into my pajamas at home, curl up on my big chair, and read a book that had nothing to do with research or improving myself or getting better at life or whatever. My resistance to feeding my addiction was gone; I was a hungry junkie looking for a fix.

I looked around, almost in a panic. My eyes fell on the table right in front of me and saw Glennon Doyle-Melton’s Carry On Warrior, which I had yet to read, and instantly my high was secured.

At home, curled into my chair and cat purring on my lap, I shot up with text and the familiar scent of a newly printed friend. Glennon started talking about holes. God-sized holes that she had learned about from another one of my authorial loves: Anne Lamott. Instantly, I was transported back in time, to that gloomy room with my father, where the man was talking about holes and prescribing me to a life of doom.

Even then, I remember, I rebelled.

I must have been, what? Fifteen, maybe? The odds had finally played out for my dad, and he’d gotten pulled over on the way home from his nightly pit stop at his usual place. Over the years, before and after this event, this particular bar was his second home. I wouldn’t be surprised if they’d put a beer in front of his stool even when he wasn’t there.

It’s the kind of place that when he fell off that bar stool and broke his elbow, they drove him home for once. This was the kind of place where a guy could die propped up on a bar stool in the corner, and no one would notice until closing. It was the kind of bar where kindred, broken spirits gather to share their own special kind of communion, a fellowship of avoidance, a ritual of silence about the things that matter, a rapport of pub talk of the topical sort.

My dad still is, even now, a social butterfly, a friendly guy who loves a good laugh, the tragic hero who feeds hungry people without anyone knowing, who slips five dollar bills to my kids when I’m not looking, and who hides deep, festering wounds behind his silence and glittery blue eyes — the eyes he’s passed down to my son.

When I look at him now, sitting in his chair, dozing in his old age, I wonder about the memories that haunt him. The autopsy of the murdered baby he had to watch as the cop who took the report of the psychotic mother? The Christmas his parents gave him literal coal in his stocking? I took down my grandparent’s picture after I found out about that one.

It’s easier to forgive your parents when you think about them as children.

He lost his license that night he got pulled over. The cop followed him all the way to our house, lights flashing silently against the blackness of the night, so all the neighbors could watch out their windows. As part of his sentence, he was required to complete a court-approved addiction program, and damn it, they made me go with him.

The cheery little room of doom and gloom, with the guy and his holes. This one was for the addict and their kids. The point, as far as I could tell, was to guilt the parents into recovery by explaining how damaged their children were as a result of their illness.

A co-dependent child is now left with holes, the man at the front of the room said. He wore khakis and had glasses and was balding on top. He had the energy and charisma of a slug.

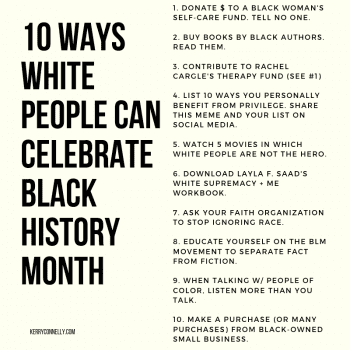

These children will fill their holes with all sorts of things. He wrote a list on the board among the circles.

Alcohol

Drugs

Sex

Shopping

Gambling

Food

Anorexia / Bulimia

I could feel my father get smaller beside me as the man droned on with his hopeless drivel. Hope had been sucked out of that room with the light, stealing any energy of birth, renewal, creativity. I was not yet a Jesus Freak, but I had a sense of God. I believed in God the way you believe in a friend you once had, but haven’t spoken to in years. It seemed even this man who was teaching us, a counselor of some sort, presumably, didn’t believe anything good could come from any of us there in that room.

If there is a hell, I’m pretty sure it feels like that room.

I was angry as we left. I rebelled against that hopelessness. I was actually angry enough to say out loud what was on my mind, which for me, back then, was very strange, and very rare. Even now it feels dangerous; I have just gotten more used to the risk.

We walked out into the night, my father small and silent beside me, his lips resigned. Why can’t I fill my holes with something good? I finally said out loud. Why does it HAVE to be all that shit? Why can’t it be something good?

Was I naive? Maybe. I was wise enough to know I had holes, even at that young age. My father did not respond. My question echoed in the night and went unanswered, eternally rhetorical, bouncing off the cosmos on its way to infinity.

Why can’t I be filled with something good?

Over the years, I have tossed my share of shit into those holes, and I have danced along their edges, my safety precarious. Sometimes my holes come raging up like strange monsters in a bad movie, all sharp teeth and goo, and they surprise me with their ferocious hunger.

But none of the things that man listed on that board has ever really satisfied them. Even I am surprised when I go to Target now and come out with nothing, because everything there seems cheap and wholly unnecessary. What a strange thing for me to feel, walking through my beloved Target, credit card at the ready, and no desire to buy.

I don’t know why I never fell all the way into those black holes. Other members of my family did and some have paid ultimate price for it. I don’t know why I didn’t. Is it that rebellious hope? That God-seed that somehow got planted in my heart? I take no credit for it. It was just there, like the color of my hair or the way my fingernail curls on my left pinky finger.

It was as if God was there the whole time, reaching out a hand, sometimes, maybe, even holding fast onto my collar as I attempted to leap. The fact that God held on is nothing but grace and more grace.

I think this is why when I picture Jesus, I am most comfortable with envisioning Him as a subversive and a rebel. Some picture him as a hippie. Others in the capital E world of Evangelicalism, with their toxic masculinity, like to picture him more like a football player.

But I think of Jesus, and I think He is a subversive hope, a rebellious hope. A hope that gives the finger to deep, black holes that gobble up children of alcoholics. I think Jesus is a hope that says Screw you, addiction. I’m here now. And I’m turning on the fucking lights in this dark room.

I think sometimes maybe Jesus would have had a pierced and tattooed soul, with every one of our pains inked into his heart, and all that grace that has to pour out from somewhere, so his soul needed its own kind of holes.

It’s why I recognize Jesus and he recognizes me.

Our holes match.

His wholeness fills my holes.