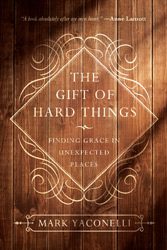

Bloggers note: Sometimes I write a blog post and it comes nice and neat in a little package. Other times, the words meander and take huge detours of thought, intersecting only rarely with each other. This piece, I’m afraid, might be the latter. I know readers prefer that I have a point, but Mark Yaconelli’s book, The Gift of Hard Things, is such a moving, beautiful construction, I had a hard time sticking to one theme, other than that God is pretty awesome, even when life sucks. So I’m sorry for the lack of — what? structure? — in this piece. But it does give you a glimpse at my writing process, if that were something of interest to you.

Bloggers note: Sometimes I write a blog post and it comes nice and neat in a little package. Other times, the words meander and take huge detours of thought, intersecting only rarely with each other. This piece, I’m afraid, might be the latter. I know readers prefer that I have a point, but Mark Yaconelli’s book, The Gift of Hard Things, is such a moving, beautiful construction, I had a hard time sticking to one theme, other than that God is pretty awesome, even when life sucks. So I’m sorry for the lack of — what? structure? — in this piece. But it does give you a glimpse at my writing process, if that were something of interest to you.

Back in college, I once took a cultural anthropology class in which the professor taught that we humans tend to categorize things to make order of our world. Often, culture clashes come when we categorize things differently — for example, in the United States, most of us put dogs in the “pet” category, while in other countries, dogs might be put in the “food” category. Consider your response to that example, which might be quite visceral, and you’ll understand how strongly embedded those socially constructed categories can be.

We categorize God in much the same way. We try to fit God into nice, orderly columns and rows, a divine spreadsheet that can spit out a pretty little data-filled pivot table of do’s and do not’s, rightness and well-thinking, theologies and exegesis.

Mark Yaconelli’s The Gift of Hard Things takes those columns and rows, however, and gives us permission to turn them into a Jackson Pollack painting, a MoMA-worthy splatter art canvas of God’s expansion into the hard places, the foggy places, the places where God is unknowable, and his unknowable-ness is perhaps his greatest comfort offering.

I cried more than once reading this book. When I didn’t even want to, I wept.

I cried because I was so very young when I started to understand that life’s greatest sense of joy was only sweet because of the sorrow from which it was borne. I cried because God was there, first, in an unknowable way that is so very certain in the fabric of my soul, before I became broken and tired, He was there.

I was on the pebble-strewn dead end street on the side of my house on the sun-shiniest of days. As usual, I was alone, perhaps three or four years old. And suddenly, the sense of a large, loving presence standing beside me, protective. Of leather sandals on dirty feet beside me, of warmth, and total love, and complete acceptance despite my overzealous-for-everything nature, despite the dirt on my legs. Despite my messy, sticking-straight-up hair. Jesus stood next to me that day and loved me. No — he didn’t just love me. He was enthralled by me. It was the kind of love that makes you know there’s never anything you can do to fuck it up.

And that same day, in that warm sunshine, as I sat on the pebbles, a butterfly landed on my nose. I remember so clearly what it’s like to stare into a butterfly’s eyes, because this one landed on my nose and stayed for a while, slowly moving it’s wings to and fro. And in that moment I felt Jesus speak to my heart and say, I choose you.

That knowing, that day, laid a foundation of peace that sits behind the anxious, the hurting, the scared person that life created out of the conglomerate of cells that is me. And somewhere in that knowing lay the understanding that, as Yaconelli says, “I had a deep awareness that one of the invitations in this life is to hold confusion, frustration, and suffering as possibility.” (pg 11) It’s such a strange idea, this possibility inside of suffering.

Grace is such a wide open space, there’s room in there for pain, too.

I make spreadsheets for my business — I categorize numbers and potential profits. I forecast expenses and potential income. And I am always wrong — my business, my life, my human potential, my path is always bigger and different that what I have planned. And when the hard things come — and they always do — I am met with an even bigger God, a God who blasts the boundaries of the columns and rows into which I try to squeeze him, and who he might be, to oblivion.

I carry the scars of my hard things like most do — my fears, my anger, my hurts and my grudges. I nurse them, hone them into sharpened edges. Despite the softness of that sunshiny day with Jesus, my edges do get sharp. This is what can happen in our hard things — we grow up to be hard-edged, jagged, and we accidentally slice through life, through the people around us, even when we don’t mean to.

Take our fear and our anger. If we could plot them on a pivot chart — oh, the chart our country would make these days! How we are being played by the media, by the politicians. How our anger and fear is being used like a weapon against us, to manipulate us like pawns. But what if, in these hard things, our country took the blessing God is offering us?

What if all the people yelling Blue Lives Matter, or the people who get mad at the people who yell Blue Lives Matter, could all just

…receive the anger of others as a cry for justice, a cry for respect, a cry for safety? What if I could see my own anger as a sign of God’s yearning for right relationship? What if…every time I felt I angry I stopped, stood still, and listened more deeply?

Back in 2011, Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz was set to speak at the Global Leadership Summit, but cancelled because an online petition at Change.org called the summit hosts, the Willowcreek Association, anti-gay. I remember when this happened a friend of mine who holds a traditional view on sexuality and, I think, really does believe there is a war on Christianity, got a little puffed up about this. In fact, he almost gloated — See? See what the gays did? And my response was, Listen for the pain. There’s pain in that petition, and we’re responsible for it.

Yaconelli captures this type of discourse so perfectly in this book. He shows us how we can move into the pain of hard things, and find God there in the middle. He says, “There can be no real hope unless it somehow embraces, unashamedly, the presence of real suffering in the world.” (pg. 98). He goes on to say on page 99:

We do not become hopeful by talking about hope. We become hopeful by entering darkness and waiting for the light. We become hopeful by being honest with one another about our pain and then waiting, together, for God to show us a way toward healing.

Might I be bold enough to add that we don’t find hope and healing through our hard edges, the pointed tinge of a shrill yell, or through waving placards. Might I be bold enough to add that we find hope in the softness of listening ears, of rounded hearts, of quiet tongues.

A friend of mine was lamenting her lack of patience with people, her inability, she thinks, to lead because of her hardness. But she has serious emotional trauma in her childhood. I encouraged her to look at a five year old, start to understand what a five year old is really like. Then say thank you to her inner five year old for getting her this far. When she asked how that would help soften her edges, I said, “Because when you can see your own inner five year old, you can see other people’s five year olds, too.”

Maybe that’s what God’s grace helps us to do — to see the inner five year old in all of us. Regardless of our uniforms, regardless of the skin we wear or its scars, maybe God can help us all see the five year olds, who maybe have butterflies on our noses.

Maybe we need to stop giving God a whole bunch of nicknames that don’t fit, column headings that really don’t contain who he is. Yaconelli says on page 119 that he “suddenly realized that what was driving [his] life was not God but a mixture of wounds and desires. What [he] had named God was not God.”

Perhaps most of all, if we can rest in the assurance that God is in the empty columns, too, those places where it seems he has left us for dead, we might find a spring of living water to refresh even the deepest thirst. Can we divine this living water from the driest of deserts, where the hurt and the anger and the annoying people are too thick to see through? Where our pains seem deeper than life itself? Where are grudges are stubborn? Maybe.

Just maybe. As Yaconelli says:

Over time I have learned that if I can stay with the discomfort, the absence, the hurt, the grief (often only through the help of others), these hard experiences can soften my heart, expand my vision, and open me to a new awareness of the deep truths of God.

Surely there is sustenance there.

__________________________________________________________________________