Every time I look through the contributors to The Apostle Paul and the Christian Life: Ethical and Missional Implications of the New Perspective (ed. J. Modica, SMcK), I think that specific contributor’s essay was my favorite to read. Which brings to my “new favorite,” the essay by Patrick Mitchel, principal at Belfast Bible College and formerly at Irish Bible Institute. Mitchel brings a different angle — not just the Irish angle — to this discussion because he is a theologian and not a New Testament specialist. Like the great theologians of the church — Athanasius, Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, Barth — Patrick Mitchel fashions theology on the basis of Bible study (not just the history of dogmatics) and, adding spice to his theology, he’s got a great perception of narrative theology. I’m not blowing smoke here — I’m introducing you to a very good theologian.

Every time I look through the contributors to The Apostle Paul and the Christian Life: Ethical and Missional Implications of the New Perspective (ed. J. Modica, SMcK), I think that specific contributor’s essay was my favorite to read. Which brings to my “new favorite,” the essay by Patrick Mitchel, principal at Belfast Bible College and formerly at Irish Bible Institute. Mitchel brings a different angle — not just the Irish angle — to this discussion because he is a theologian and not a New Testament specialist. Like the great theologians of the church — Athanasius, Augustine, Aquinas, Calvin, Barth — Patrick Mitchel fashions theology on the basis of Bible study (not just the history of dogmatics) and, adding spice to his theology, he’s got a great perception of narrative theology. I’m not blowing smoke here — I’m introducing you to a very good theologian.

Patrick once pointed me to a number of good books about Ireland’s turbulent, political theology and theological politics, I read them and came to the conclusion that it might take five years of reading to comprehend the many layers at work in Ireland. Patrick loves Ireland and the churches of the Republic and Northern Ireland, and so he brings to this discussion about the Christian life and the new perspective fresh pastoral angles that cut into the fabric of national and social concerns.

Patrick brings this much needed freshness in the subtitle to his essay: “Solus Spiritus.”

Patrick brings this much needed freshness in the subtitle to his essay: “Solus Spiritus.”

Unlike other contributors to this volume, I have not written a book related to the apostle Paul. I write as a theology lecturer with particular interests in Christology and pneumatology, familiar with the issues raised by the NP and passionate about teaching and preparing students try in a post-Christendom culture on the western edge of Europe. I also write as a church person: an elder in a developing church-plant; a teacher and preacher who—since the Pauline corpus makes up most of the New Testament—faces regularly the task of bridging the hermeneutical gap between Paul’s world and ours (71).

Hence, he says this about Paul later in his essay:

I like to think of Paul (and indeed all the writers of the New Testament) as an inspired reflective practitioner. I use the word inspired deliberately, to resist a reductionistic reconstruction of Paul that leaves little or no room for divine revelation to explain his transformation from persecutor to persecuted (83).

This is the cutting edge of theology: where it meets church and where church meets theology, and where church and theology interact with society. One of the best sketches to date of the new perspective can be found in the first major section of Patrick’s essay, and he articulates this important point about the “old” perspective: “A corollary of the first concern [Judaism as a works righteousness religion] was that the OP led to a gospel of ‘bad news’ prior to the announcement of ‘good news'” (73). This is often rooted in the “legalistic Jew” in all of us, and this old perspective’s mistaken perception of the relationship of justification to sanctification and between faith and works (see the previous essay by B. Longenecker). Patrick also shows that the old perspective tended toward a preoccupation with individualism. [It is not a little ironic that one of the critiques by some defenders of the old perspective is that new perspective folks don’t have room for the individual and the personal — the irony is that in that critique the old perspective critic is displaying the problem the new perspective folks have seen.] His final observation about the new perspective is that it showed that the old perspective too often ignored narrative theology shaping NT theology.

Here Mitchel enters into his expertise: how have the old perspective folks responded to the new perspective claims? First, there is a concern with how sinners are put right with God. E.g., that NT Wright focuses on the horizontal at the expense of the vertical (that is, inclusion of Gentiles in the church vs. being put right with God), future justification (it is said by critics of Wright) is tied to closely to a transformed life (in spite of Wright’s routine statements to the contrary), and Wright rejects the classic doctrine of imputation. The other major criticism has to do with divine and human agency. [I insert here some radical versions of Lutheran theology that seem to be attractive to some in the old perspective, Gospel Coalition, Together for the Gospel crowd — expressed by Preston Sprinkle.] There is more to discuss here, but Mitchel is right: both sides bring important elements to the discussion, while the old perspective tends toward centralizing soteriology in a Reformed or Lutheran mode.

The “anxious Protestant principle” of not importing works into salvation has tended to marginalize what Paul has to say on the Christian life. In other words, the priority of how to “get in” has tended to make secondary the importance of the life lived once “in.” This is despite moral formation being the goal of Paul’s missionary work among his churches, as James Thompson has shown wonderfully well (81).

Another irony about old perspective criticisms of the new perspective not having enough emphasis on the Christian life — listen to these words from Mitchel:

The result, while certainly imperfect and open to criticism in places, has in my view forged fresh ways of appreciating the integration of the apostle’s theology with how it shapes his vision for the Christian life. Once we step back from the detailed arguments, I suggest that it is easier to see that the most significant contribution of the new perspective has been how it has acted as a catalyst for a renewed appreciation for the narrative coherence of Paul’s thought. This wider angle, in turn, helps to foster a renewed integration of Pauline theology and ethics and helps to focus attention on the purpose of justification within Paul’s ecclesiology, eschatology, and pneumatology (81).

These are powerful words that bring fresh insights into the entire debate, but what has to be observed here is that what Mitchel claims is that the new perspective, contrary to its sometime critics, sheds fresh light on how Paul envisions the Christian life! This is the reason this volume was produced, to show just that.

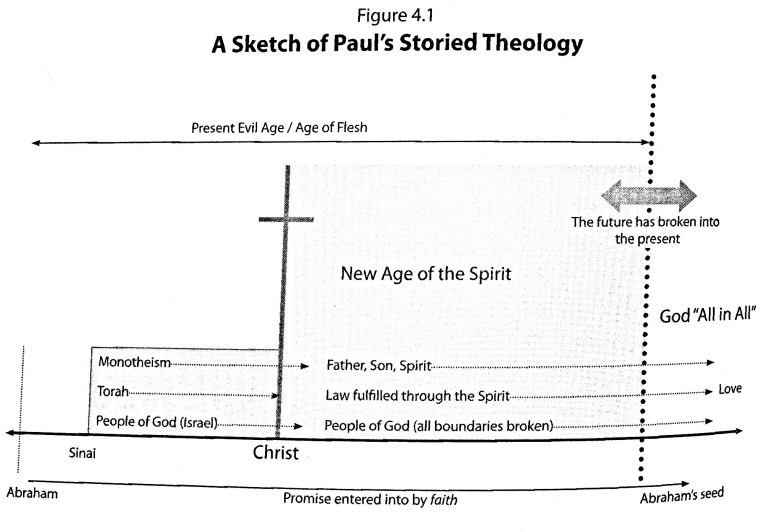

Here is Patrick Mitchel’s chart that maps Paul’s theology of the Christian life (and he offers observations showing no chart can contain it all):

Notice continuity, the covenant God makes with Abraham setting the Bible’s narrative, the importance of some discontinuity, the prominence of Spirit, and the pervasive reshaping under the influence of eschatology. This in contrast to the simplistic but appealing to some law vs. grace narrative/ideology that at times overrides all other themes.

With NT Wright, Mitchel observes a “restructuring” of monotheism, Torah and the people of God. Justification, too, then is inseparably linked to ethical transformation in the new age of the Spirit that generates transformation.