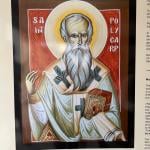

Most any reading of the earliest period of the followers of Jesus, say from 30-50 AD, reveals a more charismatic ordering of a local church. Most any reading of the 3d Century church reveals what many call a Monarchial bishopric, where we have an authoritative teacher “ruling” the local church. How did this happen?

Most any reading of the earliest period of the followers of Jesus, say from 30-50 AD, reveals a more charismatic ordering of a local church. Most any reading of the 3d Century church reveals what many call a Monarchial bishopric, where we have an authoritative teacher “ruling” the local church. How did this happen?

Everett Ferguson, in his The Early Church and Today (vol. 1: Ministry, Initiation, and Worship) maps various moves in the rise of the monarchial bishop. Ferguson operates with an almost “cessationist” theory, namely, that apostles and prophets particularly died out and the church was then ruled by local bishops and elders.

What do you think of this development? Was it inevitable to become more organized and administered or was it a “fall”?

First, a time of extraordinary inspired ministers. Here he sees three primary gifts, found in 1 Cor 12:28: “apostles, prophets, and teachers.” His definitions of each are standard: special call and plenary inspiration for apostles; prophets had a less abiding inspiration. Teacher had a word of knowledge and locally exhorted and instructed.

Second, a time when both inspired and “uninspired” (he means something special here) dispensed the Word. He sees Ephesians 4:11 as a time of transition: evangelists (universal gift) and pastors (local churches). These did not require a miraculous gift (this is what he means by “uninspired” — though I think this choice of terms is not helpful). Pastors are elders or bishops.

Third, a time when the uninspired became permanent. Here he points to 1-2 Timothy and Titus. The inspired gifts are dying out and we get “offices.” Churches are ruled by presbyter-bishops (elders). This is a permanent feature of the church after the inspired apostolic, prophetic era of revelation. Women were teachers but he thinks they were not permitted to teach in the public assembly. [I disagree with Ferguson here because it seems to me he’s got a more rigid sense of church assemblies than I would have.]

Fourth, a time when there was a decline in universal and missionary work so that local officers ruled the entire church. Fifth, single bishops (episcopos) arose in distinction from local elders (presbyters). Sixth, the monarchial bishop was established.

This 4-6 period is when “apostle” is used almost exclusively for the Twelve. “No one called a contemporary, not even the bishops who were regarded as successors of the apostles, by the title ‘apostle'” (28). I must add here that I find the present use of “apostle” by some groups to be flat-out weird and uninformed. The prophetic order, Ferguson argues, also dies out at this time. He speaks of the “extinction of the prophets” (28). Teachers appear but he finds the inspired teaching gift fading and was submerged under “episcopal domination” (29). In other words, leaders were called “bishops” not “teachers.” Evangelists fade, too, and he sees this as a problem complicated by the growth of local church ministries.

The result was that one man was recognized in each local church as the bishop. He is the chief among equals at first but eventually gains status to become the single bishop of the monarchial bishop.