God’s manifold mercy, God’s lovingkindness that embraces us in our manifold needs, is the hope of the psalmist in the next section (waw-section; 119:41-48). His prayer: “May your steadfast love reach me.”

God’s manifold mercy, God’s lovingkindness that embraces us in our manifold needs, is the hope of the psalmist in the next section (waw-section; 119:41-48). His prayer: “May your steadfast love reach me.”

That lovingkindness is understood here as “deliverance” (v. 41b), and that deliverance is understood as “an answer for those who taunt me” (v. 42).

God’s mercy is manifold: it comes to us where we are — in all our concrete particulars. Moms and dads, men and women, children, students, teachers … and we could go on to list everything we do and all the kinds of folks we are. In each of those particulars, God manifests his manifold mercy.

The psalmist reminds me of something important: no matter how small I am, no matter how small my concern, God hears. His infinity so intense and extensive, that God knows and cares about everything. All this psalmist wants is the capacity to answer his opponents.

If we are tempted to think we should bring only the big ones to God, the psalmist evidently thinks otherwise.

Psalm 119:43 is odd: “Never take your word of truth from my mouth, for I have put my hope in your laws.” My rabbi commentary, by Samson Hirsch, says this: “Do not make it appear as if my mouth had said something entirely untrue when I pointed out Thy righteous ordinances to my opponents.”

This is what I meant when I said the psalmist thinks God cares about everything he does and says. His God cares about everything.

His care here is for eloquence or at least clarity; his fear is getting tongue-tied or confused when he is on the spot about the mishpatim, the commandments. He simply prays to be simply clear when he speaks about what he believes and what he observes.

Frankly, I struggle to think of a context for this kind of prayer for the psalmist: Is he being called on the spot for his understanding of Torah? of the kind of observance he is committed to?

Not sure, but the psalmist knows God cares.

When we combine the Reformation (e.g, esp Lutheran) antithesis of law and gospel with pietism’s and Liberalism’s and the Western democracy’s sense of individual freedom, it is not hard to predict that many will find “rules” difficult expressions for genuine spirituality. And here (Ps 119:43) the psalmist claims he “puts his hope in” or “rests himself in” God’s ordinances, rules, or mishpatim.

I am reminded of Isa 42:4: “In his teaching (torah) the islands will put their hope.”

Isa 51:5: those same islands hope in God’s “arm”.

Mic 7:7: “But as for me, I watch in hope for the LORD, I wait for God my Savior; my God will hear me.

Psalms are rich in hoping in God and in God’s communicative rules with humans: “But the eyes of the LORD are on those who fear him, on those whose hope is in his unfailing love” (33:18; see 43:5). And in 119, vv. 74, 81, 114, 147.

My point: there is a delicate interplay here between God and God’s expression in words so that the word becomes the expression of God’s personal presence. It is not that the psalmist trusts in word but in the words of the Torah/mishpatim as God’s words.

His hope is in that kind of wordiness, that kind of expressiveness from God to him. He believes the very words of the Torah are God’s communicative event and he has put his hope in those words.

Psalm 119:44-48 is an interplay between “going public” about commitment to Torah and the joy that comes from that Torah. The going public can be found in vv. 44, 46, 48, and the joy in vv. 45 and 47. Today “going public”; tomorrow the “joy.”

I will always obey your Torah (44); I will speak of your “testimonies” and not be ashamed in the presence of kings (46); I reach out for your commandments (mitsvot).

Called into the presence of the powerful royals, the psalmist will not back down. “Always” (44) — because he loves the mitsvot — he is committed to God’s Torah.

His publicity is in terms of observance (44), speaking (46), and “reach out his hand” for the commandments. This last expression could refer to reaching out one’s hands into the air as a physical act of reaching out to God. Thus, in 63:5 it is the posture of invocation before God. Thus, the psalmist is public in observance, in communication, and in posture — he is devoted to God with his whole heart, soul, and strength.

Psalm 119:45 and 47 are delightful lines: “I will walk about at ease” and “I will delight in Your commandments.” That first line is evocative.

The notion is to walk in expansiveness, with room to spare, in freedom. The idea is “relief” (4:1), roominess for the feet as one walks (18:36), freedom from anguish (25:17), opening one’s mouth so God can fill it (81:10), the vastness of the sea (104:25), and the boundlessness of God’s commands (119:96).

The commands, acc to the psalmist, liberate because one hears God, walks with God, and learns of God how to walk in this life. The commands are “roomy” because they provide guidance and sure-footedness to the traveller. They are expansive because they give the observant the sense of confidence, of knowing where they are, as they wander through this life with God.

It is delightful, the psalmist to be at ease with God in this world. It is Torah joy.

Dennis Venema, a Christian biology professor, spent the first half of the new book

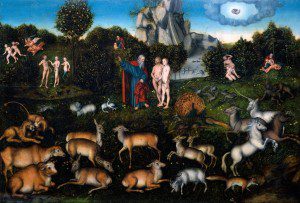

Dennis Venema, a Christian biology professor, spent the first half of the new book  Honesty. We need to be honest about the Bible and about science – to face the facts rather than fear them. The differences between the order of creation events are part of the data, not problems to be solved. If we respect the Bible we will be honest in the way we read and wrestle with it. Scot brings up the example of Genesis 2:19. The Hebrew is more consistent with the NRSV “So out of the ground the Lord God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air,” than the NIV “Now the Lord God had formed out of the ground all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky.” Unfortunately the NRSV translation, like the Hebrew, places the creation of the man before the creation of other animals, in contrast to the creation order in Genesis 1. The NIV translation is an attempt to harmonize Genesis 1 and 2. Not even a footnote to indicate ambiguity. This is not a respectful translation. “This oddity in translation illustrates the tension between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, and that tension deserves to be kept – for that is the most honest reading of the text.” (p. 102)

Honesty. We need to be honest about the Bible and about science – to face the facts rather than fear them. The differences between the order of creation events are part of the data, not problems to be solved. If we respect the Bible we will be honest in the way we read and wrestle with it. Scot brings up the example of Genesis 2:19. The Hebrew is more consistent with the NRSV “So out of the ground the Lord God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air,” than the NIV “Now the Lord God had formed out of the ground all the wild animals and all the birds in the sky.” Unfortunately the NRSV translation, like the Hebrew, places the creation of the man before the creation of other animals, in contrast to the creation order in Genesis 1. The NIV translation is an attempt to harmonize Genesis 1 and 2. Not even a footnote to indicate ambiguity. This is not a respectful translation. “This oddity in translation illustrates the tension between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, and that tension deserves to be kept – for that is the most honest reading of the text.” (p. 102)

Evolution can be design. We should move away from the idea that evolution and design are mutually exclusive. God can and does work through a wide range of process that we consider “natural.” The distinction between natural process and divine action can distort our view of God’s work in his creation. The Bible gives us examples of God working personally with his people. Moses saw God, God spoke through visions and through prophets. The incarnation, the life, death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus is the most important example. But the psalmist can also write “you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (139:13) as a testimony to God’s providence, not a repudiation of “natural” embryonic and fetal development. There is nothing inherently atheistic about evolutionary processes. Dennis asks “Could it be that God, in his wisdom, chose to use what we would call a “natural” mechanism to fill his creation with biodiversity adapted to its environment?” and “If he did, would he be any less a creator than if he had done so miraculously?” (p. 90) I am convinced that God could, in his wisdom, use evolutionary processes and that this is completely consistent with our understanding of God as creator. On this question then, the wisest approach is simply to let the science take its course. We need not jump on every bandwagon, but we also need not fear the ultimate conclusions, whatever they are. We should be more concerned with the metaphysical conclusions that some people attempt to weld onto the science as though they were all one piece.

Evolution can be design. We should move away from the idea that evolution and design are mutually exclusive. God can and does work through a wide range of process that we consider “natural.” The distinction between natural process and divine action can distort our view of God’s work in his creation. The Bible gives us examples of God working personally with his people. Moses saw God, God spoke through visions and through prophets. The incarnation, the life, death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus is the most important example. But the psalmist can also write “you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (139:13) as a testimony to God’s providence, not a repudiation of “natural” embryonic and fetal development. There is nothing inherently atheistic about evolutionary processes. Dennis asks “Could it be that God, in his wisdom, chose to use what we would call a “natural” mechanism to fill his creation with biodiversity adapted to its environment?” and “If he did, would he be any less a creator than if he had done so miraculously?” (p. 90) I am convinced that God could, in his wisdom, use evolutionary processes and that this is completely consistent with our understanding of God as creator. On this question then, the wisest approach is simply to let the science take its course. We need not jump on every bandwagon, but we also need not fear the ultimate conclusions, whatever they are. We should be more concerned with the metaphysical conclusions that some people attempt to weld onto the science as though they were all one piece.