There’s Something about Joseph, by Jason Micheli

Matthew 1.18-25

The sermon begins without explanation, with random volunteers from the audience performing updated parts of the ritual for the bitter waters:

First, barley is measured out of its package- 2 quarts worth- and poured into an offering plate.

Second, holy water is poured from the baptismal font into a large clay pitcher.

Next, the ‘indictment’ is written on a piece of parchment and then its burnt, its ashes put into the water and mixed together.

Then, the pen with which the indictment was written is unscrewed and the ink is poured into the pitcher of water.

Finally the floor of the altar is vacuumed and the suctioned dirt is removed from the bag and put into the pitcher. It’s all mixed together a last time and poured into a clear glass.

‘Does anyone want a drink?’

There’s something about this (the bitter waters) story, and there’s something about Joseph that always makes me think of my boys.

But it’s not for the reason you might guess.

Sure it’s true that Jesus isn’t Joseph’s biological son.

It’s true that, like me, Joseph is an adoptive father.

It’s true that in Jewish tradition as soon as Joseph names him and claims him as his own- adopts him- Jesus is as much Joseph’s child as he would be had Joseph been the biological father.

And it’s true that I know firsthand how true that is and feels.

But that’s not it.

That’s not the something about Joseph that always makes me think of my boys.

Matthew says that Joseph was a ‘righteous man.’

And that’s all Matthew has to say.

I know Matthew’s nativity sounds like a short, simple, straight-forward story, but that’s because we live on this side of Christmas.

On the other side of Christmas it’s not a simple, straight-forward story at all.

And it all hinges on Matthew calling Joseph a ‘righteous man.’

In Hebrew the term is ‘tsadiq.’ And it’s not just an adjective for someone.

By calling Joseph a righteous man, Matthew’s not simply saying that Joseph was a good man or a moral man or even a God-fearing man.

Tsadiq in Matthew’s day was a formal label. An official title.

Tsadiq was a term that applied to those rare people who studied and learned and practiced the Torah scrupulously.

Tsadiqs were those rare people who believed the Jewish law was the literal Word of God as dictated to Mose, and therefore, as the Word of God, tsadiqs believed the Torah should be applied to every nook and cranny of life.

When Matthew tells you that Joseph was one of those rare, elite tsadiqs- righteous men- Matthew tells you everything you need to know to unlock this story.

Because when Matthew tells you that Joseph was a tsadiq, he’s telling you, for example, that Joseph wore phylacteries, little boxes of scripture against his head and around his arm- as commanded in Deuteronomy 6.

When Matthew tells you that Joseph was a righteous man, he’s telling you that Joseph wore a prayer shawl at all times as commanded in the Book of Numbers 15. A shawl with tassels hanging from every corner, each tassel a tangible reminder of all the commands of God.

When Matthew tells you Joseph was a tsadiq, he’s telling you that Joseph had a long, never-trimmed beard, a beard that would fill me with envy, a beard that would set him apart as different and holy- just as Leviticus 19 commands.

Joseph was a ‘righteous man,’ says Matthew. A tsadiq.

Which means there were specific things Joseph did and did not do.

As a tsadiq, Joseph covered his right eye and prayed the shema twice a day: ‘Shema Yisrael, adonai eloheinu, adonai echad.’

‘Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.’

And as a tsadiq, you can bet Joseph had a copy of this prayer rolled up and nailed to his doorpost.

If Joseph was a tsadiq, then he gave out of his poverty to the Temple treasury.

He traveled the 91 miles from Nazareth to Jerusalem every Yom Kippur to have a scapegoat bear his sins away.

He practiced his piety before others to remind them that God had called them to be perfect, as God is perfect.

Joseph was a righteous man, Matthew says. A tsadiq.

Meaning, there were specific things he did and did not do.

He did not violate the Sabbath, no matter what, because God created man for the Sabbath, for the glory of God.

And as a tsadiq, Joseph did not eat unclean food.

For that matter, as a tsadiq, Joseph did not eat with unclean people: gentiles or outcasts or sinners.

When Matthew tells you that Joseph was a righteous man, he’s telling you that Joseph was one of the rare few who could be called ‘righteous’ because they lived the righteous law of God to the letter.

Every jot and tittle.

If the Torah commands that you care for the immigrant in your land then a tsadiq does just that without questioning.

And if Torah commands that you avoid and dare not touch a leper, then a tsadiq obeys God’s righteous law and keeps his distance.

In Israel, in Matthew’s day, after being a priest there was no greater honor than being given the title tsadiq- a righteous man who follows every letter of God’s righteous law.

And that’s the incredibly complicated dilemma that Matthew hides behind that word ‘tsadiq.’

Because this tsadiq is engaged to a woman named Mary.

And she’s pregnant.

And he’s not the father- of course he’s not.

He’s a tsadiq.

You see, in Mary and Joseph’s day, betrothal was a binding, legal contract.

Only the wedding ceremony itself remained.

Mary and Joseph weren’t simply fiancees.

For all intents and purposes, they were husband and wife.

They were already bound together and only death or divorce could tear them asunder.

For that reason, according to Torah, unfaithfulness during the engagement period was considered adultery. Actually, according to the Mishna- which is Jewish commentary on the Torah- infidelity during betrothal was thought to be a graver sin than infidelity during marriage.

Matthew tells you that Joseph is a tsadiq.

Betrothed to an adulteress.

As a tsadiq, Joseph knows what the Torah now requires of him.

Joseph can’t simply forgive Mary and forget.

Only God can forgive sin.

No matter how much Joseph might love Mary, his love of God must trump his love of neighbor- they’re not equivalent. According to the Book of Deuteronomy, Joseph must take Mary to the door of her father’s house, accuse her publicly of adultery and say to her: ‘I condemn you.’

And if she does not protest or deny the accusation, the priests and elders of Nazareth will stone her to death. On her father’s front porch.

That’s what the Torah commands.

And Joseph, Matthew tells us, is a tsadiq. A righteous man.

Of course, if Mary does protest, if she denies that she’s sinned, if she’s foolish enough to tell people something as ridiculous as her child being conceived by the Holy Spirit then Joseph, as a tsadiq, certainly knows what course of action the Torah requires: the ritual of bitter waters.

According to the Book of Numbers, Joseph is commanded to take Mary before a priest, bringing an offering of barley with them. About 2 quarts’ worth.

After offering the barley upon the altar, the priest will compel Mary to stand before the Lord.

The priest will pour holy water into a clay jar. Then the priest will sweep up the dirt from the synagogue floor and pour it into the jar of water. Then the priest will write and read out the accusation against her and Mary will be compelled to say: ‘Amen, amen.’

Finally the priest will take the accusation and the ink in which it was written and mix them into the water.

And then command Mary to drink it.

The bitter waters.

If it makes her sick, she’s guilty and she’ll be stoned to death.

If somehow it does not make her ill, then she’s innocent.

Her life will be spared though, in Mary’s case, her life still will be ruined because she’s pregnant and Joseph’s not the father.

She will be considered a sinner. Specifically, an am-ha-aretz, a term that was reserved for people like lepers and tax collectors and shepherds.

And as a tsadiq, someone who lives the Torah inside and out, Joseph certainly knows he’ll be considered an am-ha-aretz too if he marries Mary.

He’ll be a tsadiq no more.

On the other hand, if he does anything other than, anything less than, what the Torah commands he will be a tsadiq no more. He will lose his status as quickly as though it were emptied and poured out from him.

But that’s what Joseph chooses to do.

Matthew says in verse 19 that ‘Joseph resolved to…’ but Matthew leaves it to us to imagine just how long it must’ve taken Joseph to come to that decision.

And it’s not like Joseph’s happy about it.

That word in verse 20 that your bibles’ translate ‘considered,’ the root word in Greek is ‘thymos.’ It can mean ‘to ponder’ as in ‘to consider’ or it can mean ‘to become angry.’

It’s the same word Matthew uses in chapter 2 to describe King Herod’s anger at learning the magi have escaped him.

It’s the same word Luke uses to describe how the congregation in Nazareth responds to Jesus’ first sermon right before they try to kill him.

So it’s not like Joseph is happy about it.

But still, Joseph decides to violate the Torah by refusing to condemn Mary.

Joseph ignores his obligation as a tsadiq by refusing to have Mary’s guilt tested by the bitter waters.

Joseph forsakes his power and privilege as a tsadiq for Mary’s sake, for a sinner’s sake.

He decides to divorce her in secret.

He chooses love over the letter of the law.

He chooses compassion over condemnation.

He chooses sacrifice over safety and self-interest.

And here’s the giant thing Matthew hides in these few, little verses:

Joseph makes that choice before the angel Gabriel ever whispers a word to him.

Joseph chooses this path before he finds out that Mary is anything other than exactly what people will assume she is.

Flash forward 30 years or so.

And the boy that Joseph made his own is all grown up.

And one day Joseph’s boy meets a woman at a well.

Jacob’s well.

Even though it’s almost dark and Torah commands that they shouldn’t be talking with each other, especially at night, Joseph’s boy sits down next to her and does just that. The woman’s had 5 husbands and the man she’s with now, she’s not married to. Which, according to Torah, makes her guilty of adultery.

According to Torah, she’s exactly the type of person who deserves to be given the bitter waters.

But instead Joseph’s boy, who doesn’t even have a bucket, offers her something that sounds like the opposite of bitter waters: Living Water.

Like father.

Like son.

And one day, Joseph’s boy is at the Mt of Olives and a group of experts in the law- tsadiqs- come up to him, carrying stones and a woman they’ve caught in adultery.

She’s guilty.

And Joseph’s boy knows what the Torah commands. He can probably cite the chapter and verse: Deuteronomy 22.

It’s not an ambiguous case; it’s a dare.

And Joseph’s boy looks down at the ground and responds with a double-dare: ‘Whoever is without sin may cast the first stone.’

And when he looks up the tsadiqs have all left, leaving their stones on ground. Then Joseph’s boy kneels down and looks the woman in the eyes and says the opposite of what Torah commands: ‘I do NOT condemn you.’

Like father, like son.

And one day as Joseph’s boy is leaving synagogue a leper reaches out to him and says ‘If you choose, you can make me clean.’

Because he’s not clean, Torah is clear about that.

And Torah is clear about commanding that Joseph’s boy should put as much distance as possible between himself and this leper.

But instead Joseph’s boy reaches out to him and touches him and says to ‘I do choose.’ And Joseph’s boy reaches out to him and touches him and says that to him before he heals him.

And then Joseph’s boy flees to the wilderness.

He has to- because the leper’s uncleanness has become his own.

Like father, like son.

And when Joseph’s boy returns from the wilderness he invites himself to dinner.

At a tax collector’s house.

And it’s when Joseph’s boy is seated around a table, eating and drinking with sinners and tax collectors- people who were considered am-ha-aretz by good Jews- that’s when Joseph’s boy uses the word ‘disciple’ for the very first time.

But I can’t help but wonder if maybe Joseph’s boy was the first disciple.

I can’t help but wonder if maybe he was an apprentice in more than just carpentry.

When Joseph’s boy grows up, again and again, he chooses mercy over what the law mandates.

He reaches out to women Torah says he should reject.

He teaches ‘You’ve heard it said…I know Torah says this…but I say to you…’

He talks about the spirit of the law and not the letter.

He says the law was made for us to thrive; we weren’t made for the law to trip us up.

When he grows up, this son-of-a-former-tsadiq preaches ‘Blessed are those who…’ and in doing so he redefines ‘righteousness’ in a way that was all upside down from ‘right.’

In other words, when he grows up Jesus acts and sounds an awful lot like his father.

His earthly one.

I don’t know why that should surprise us. After all, as Matthew points out, we call Jesus: ‘Emmanuel.’

God with us.

————————-

We believe that Jesus is fully God.

We believe that Jesus is God incarnate. God in the the flesh.

But paradoxically, we also believe Jesus was fully human.

As human as you or me.

Jesus stank and sweated. He spit up as a baby, and when he sneezed real boogers came out of his actual nose.

He was fully human.

And if you don’t believe that you’re committing the very first Christian heresy. Your thinking is what St John calls ‘anti-Christ.’

He was fully human.

He didn’t just seem human. He wasn’t God pretending to be human.

His humanity was not a disguise hiding divinity underneath.

His divinity did not steer his actions or control his thoughts anymore than you or me.

He was truly human. As human as you or me.

He got tired like we do. He got hungry like we do. He laughed and he wept like we do.

He sometimes lost his temper and dropped a curse word like we do (Mark 7). He got constipated and everything else I can’t get away with mentioning in church.

Just. Like. We. Do.

He was fully, completely, 100%, no artificiality, nothing missing, no faking it, human.

And that means…

that Jesus needed to be taught.

Like we do.

Jesus needed to be taught how to pray.

Jesus needed to be formed by the practice of worship.

Jesus needed to be nurtured into his faith.

Jesus needed to be instructed in how to interpret scripture

Jesus needed to be trained to give and forgive.

Jesus needed to be discipled in what it means to follow God before he ever called his disciples to follow him.

We believe that Jesus was truly human, as the creed says.

You see, Jesus taught what he taught not because it was a satellite broadcast from our Father in heaven.

No, Jesus taught what he taught because that’s what his father and mother taught him.

And that’s the something about Joseph that always makes me think of my boys.

Because if Jesus couldn’t be Jesus without his father, then my boys can’t possibly ever be like Jesus without theirs.

Without me. Without you. Without their mother.

Without a community like this one.

Jesus needed to be apprenticed into the faithful person he became.

And so do my kids.

And so do yours.

And so do I.

And so do you.

If Jesus wasn’t Jesus all by himself, then it’s ridiculous to think that we can be like Jesus all alone by ourselves.

That’s why we do what we do here.

Teaching the stories. Offering bread and wine. Baptizing with water. Serving the poor. Praying the prayer he taught us- which I’ll bet sounds just like the prayer his father taught him.

Because if Jesus needed to be discipled before he could deliver the Sermon on the Mount, then we need to be discipled before we can live it.

And we can, you know.

Live it.

Because if Christmas- the incarnation- is true, if Jesus was fully human, as human as you or me-

Then the life of Christ isn’t just an impossible ideal we admire once a week.

It’s a life we can make our own.

Because if its true that Jesus was fully human, as human as you or me, then the logic of the incarnation works the other way too.

If Jesus was as fully human as you or me, then you and I can become as fully human as him.

If Jesus was fully human, then you and I become as fully human, as fully alive, as him.

It’s not just that Jesus got tired like we do, got hungry like we do, laughed and wept like we do.

No, if Christmas- the incarnation- is true, then we can forgive like he did.

We can serve and bless and welcome like he did.

We can receive those whom others would reject like he did.

Like him, we can turn the other cheek.

Like him, we can love our enemies.

Like him, we can give our selves to an upside Kingdom.

And like him, we can live such beautiful lives that God can’t help but to raise us from the dead.

But just like him we can’t do it by ourselves.

Denis Lamoureux has a new book out: Evolution: Scripture and Nature Say Yes! In this engaging and readable book he builds on his strong background in biology and theology to explore the question of evolutionary creation. The first chapter, Trapped in “Either/Or” Thinking sets the stage. Denis opens with the story of a student in class angry at her parents, Christian school, and pastors for teaching her that “Satan had concocted the so-called theory of evolution,” that she “had to choose between evolution and creation” and that “evolutionists cannot be true Christians.” He moves on to tell his personal story of being raised as a Christian then becoming an atheist in college convinced that evolution was true and that Christianity wasn’t. He returned to faith while in the military stationed on Cyprus, but was still trapped in either/or thinking. He became convinced that evolution was a lie against which Christians should battle and believed that all “real” Christians accepted a young earth and a six day creation.

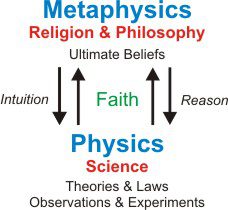

Denis Lamoureux has a new book out: Evolution: Scripture and Nature Say Yes! In this engaging and readable book he builds on his strong background in biology and theology to explore the question of evolutionary creation. The first chapter, Trapped in “Either/Or” Thinking sets the stage. Denis opens with the story of a student in class angry at her parents, Christian school, and pastors for teaching her that “Satan had concocted the so-called theory of evolution,” that she “had to choose between evolution and creation” and that “evolutionists cannot be true Christians.” He moves on to tell his personal story of being raised as a Christian then becoming an atheist in college convinced that evolution was true and that Christianity wasn’t. He returned to faith while in the military stationed on Cyprus, but was still trapped in either/or thinking. He became convinced that evolution was a lie against which Christians should battle and believed that all “real” Christians accepted a young earth and a six day creation. Metaphysics/Physics. Finally Denis introduces the Metaphysics-Physics principle. The figure to the right is based on Figure 3-2 in the book. Denis argues that it is important to realize that metaphysics and physics are complementary. Physics deals with the study of nature. “To employ the Greek word for “nature,” science investigates phusis. The English terms “physics” and “physical” are derived from it. (p. 55) Science, based on observations and experiments, theories and laws, explores the nature of our cosmos. We have learned a great deal, and we continue to learn. Metaphysics moves beyond physics. “The Greek preposition “meta” carries the meanings “after,” behind,” and “beyond.” Therefore, after we have finished our scientific investigations, we inevitably think about metaphysics and ultimate beliefs that are behind or beyond the physical world.” (p. 56) Acts of faith, accompanied by both intuition and reason, connect physics and metaphysics.

Metaphysics/Physics. Finally Denis introduces the Metaphysics-Physics principle. The figure to the right is based on Figure 3-2 in the book. Denis argues that it is important to realize that metaphysics and physics are complementary. Physics deals with the study of nature. “To employ the Greek word for “nature,” science investigates phusis. The English terms “physics” and “physical” are derived from it. (p. 55) Science, based on observations and experiments, theories and laws, explores the nature of our cosmos. We have learned a great deal, and we continue to learn. Metaphysics moves beyond physics. “The Greek preposition “meta” carries the meanings “after,” behind,” and “beyond.” Therefore, after we have finished our scientific investigations, we inevitably think about metaphysics and ultimate beliefs that are behind or beyond the physical world.” (p. 56) Acts of faith, accompanied by both intuition and reason, connect physics and metaphysics.

Scientism. I’d like to conclude this post by looking at one of the other chapters: C.S. Lewis: Science and Scientism. In this chapter he digs into the space trilogy (

Scientism. I’d like to conclude this post by looking at one of the other chapters: C.S. Lewis: Science and Scientism. In this chapter he digs into the space trilogy (

Advent, followed by Christmas is a season of anticipation and hope. Israel’s hope for the coming Messiah culminates in the birth of Jesus, the Messiah or Christ. It is fitting in this season to consider the importance of hope in human experience. Tim Keller in

Advent, followed by Christmas is a season of anticipation and hope. Israel’s hope for the coming Messiah culminates in the birth of Jesus, the Messiah or Christ. It is fitting in this season to consider the importance of hope in human experience. Tim Keller in  Personal. Keller argues that the Christian hope is personal – it preserves persons and the love relationships between persons. This personal hope gives us the anticipation of perfected love in the age to come. Human failings and self-centered focus make love a sometimes painful experience, but even this will be put right in the age to come. “If we are not a self after death, then we have lost everything, because what we most want in life is love.” (p. 167)

Personal. Keller argues that the Christian hope is personal – it preserves persons and the love relationships between persons. This personal hope gives us the anticipation of perfected love in the age to come. Human failings and self-centered focus make love a sometimes painful experience, but even this will be put right in the age to come. “If we are not a self after death, then we have lost everything, because what we most want in life is love.” (p. 167)