By Sara Barton. Sara is the University Chaplain at Pepperdine University, where she pastors, preaches, and leads a delightful and capable staff of ministers. She and her husband, John, live in an empty nest these days while their daughter Brynn is a college student and their son Nate is newly married to Falon. Sara’s book, A Woman Called, is available at Amazon.com.

By Sara Barton. Sara is the University Chaplain at Pepperdine University, where she pastors, preaches, and leads a delightful and capable staff of ministers. She and her husband, John, live in an empty nest these days while their daughter Brynn is a college student and their son Nate is newly married to Falon. Sara’s book, A Woman Called, is available at Amazon.com.

We’ve heard a lot of public language about sex this week. In rushed conversations before going to print, journalists have made decisions about what words are appropriate for the front page of our newspapers. And around dinner tables, parents have explained such things as “the p-word” to their children, hoping and praying that their explanations are developmentally appropriate. I’ve heard expressions of disbelief, outrage, even lament at the state of sexual activity and language in our culture. And there are some good reasons for that. I’ve been sick at my stomach since I heard the recording of a presidential candidate glibly using the language he did to describe assaulting a woman who had to fight off his advances. And I’ve mourned how this circus is re-traumatizing women and men who have been sexually assaulted.

But in addition to outrage and lament, faithful people must also turn inward and examine ourselves for where we’ve been complicit, where our language and actions about sex have contributed positively or negatively to the culture of sex in our communities. Salt. Light. Yeast. These are images Jesus gave Christian communities regarding our role in our wider communities. And I think it’s a good time to ask what kind of witness we are when it comes to human sexuality.

We are actually quite practiced when it comes to outrage, condemnation, and drawing lines in the sand concerning sex. Tragically, our communities are crystal clear regarding what Christians are against when it comes to sex: same-sex sex. In recent years, we’ve so reduced conversations about sexuality to homosexuality that there’s been little time or effort given to what Christians are for when it comes to sex, or if we are for anything. Whether we like it or not, that is the cultural perception of Christians in regard to human sexuality.

As one who pastors a community, my pastoral impulse this week is to proclaim the message of the Song of Songs. And here’s why: We desperately need public, communal language about sex, and we have an oft-overlooked resource in the Bible.

Found, between Ecclesiastes and Isaiah, Song of Songs is unique in several ways, one of which is the fact that it’s the only place in Scripture where a woman’s voice leads the conversation (the woman speaks 61 of 117 verses). In light of what we’ve heard lately, it seems like a good time to let a wise woman speak about sexual activity that’s right and good, a woman who not only speaks but sings and shouts about intimate, sensual, erotic passion. And in all her talk about kissing, touching, tasting, and smelling, she does not offend with crass or vulgar language. She exemplifies how it’s possible to speak about sex and intimacy appropriately. We might do well to let her teach us a thing or two.

I regularly read Song of Songs with college students in a Bible course I teach. And in that conversation, I own up to the fact that I like sex, that twenty-five plus years into marriage, my husband and I are still into each other, still engage in pillow talk with each other, and that we are learning with each passing year how to be more intimate with each other – sexually, emotionally, and spiritually.

Despite my insistence that the Song is spiritually significant, a few of my students insist that sex is not an appropriate subject for Bible class or even for the Bible. Some even vote for removing it from the canon. I often overhear at least one side conversation as my students leave, “That was awkward.” I find it ironic that “locker-room talk” is forgiven in our sex-saturated society, but talking about sex becomes awkward in Bible class. This tells me we are doing something wrong in the church.

I like to think that the Song of Songs teaches us the most when we simply let the poem do what it does, and the poem celebrates sexuality in a spiritual context. It teaches us about God and Israel, about Christ and the church. And, it teaches us about two people who help us imagine a full definition of intimacy – sexual, emotional, spiritual intimacy. That’s why the Song is in the Bible. That’s why it’s read in Jewish communities at the celebration of Passover every year. It proclaims that the celebration of sexual intimacy, a central human experience, is appropriate religious conversation for God’s people.

So, here are a couple of the spiritual lessons I’ve gleaned from the lovers in the Song and from my relationship with my husband, John through the years. I look forward to learning even more.

• The Song of Songs doesn’t allow us to make objects of one another or let us imagine we are mere objects to God. The Song reminds us that any song of objectification is off key. It’s a broken sexuality that makes dull objects of life-filled humans created in the image of God. That’s how women become objects through pornography and trophies acquired through male “grabbing” and conquest rather than real, breathing human partners. That’s how men are objectified too. In a broken view of relationships, men exist in the minds of some women as objects of lust, or perhaps as breadwinners, providers who bring home not only the bread but also the required expensive clothes, furniture, and cars. This Song won’t allow us to beat the objectification drum. It celebrates a relationship in which both partners know and are known. It’s a world in which neither partner dominates or dictates. It’s a world where both partners provide for the other. Read the poem: the shepherd initiates, but so does the maiden. He is vulnerable; so is she. She becomes insecure; so does he. And through it all, lovers are not objects to each other but real, live, breathing people who mutually give and take in an erotic relationship celebrated in a holy collection of Wisdom.

• The Song of Songs teaches us what it means to belong to someone else, not in a relationship that wields power in one direction, but in a relationship that is mutual. I love the section of the Song in chapter 5 in which he initiates intimacy, but she initially hesitates. I have taken off my robe and must I put it on again? ¨I have washed my feet; must I soil them again? She’s tired, she has already settled in for the night. She isn’t really in the mood. A moment later, however, she regrets her hesitation and runs after him. And in chapter 7, she is the one who invites him to the garden to see if the blossoms on the vine are open (wink. wink). Sex can become about abuse of power when one partner must always initiate and the other partner holds the sex key. Both partners should initiate sometimes. Both should have the freedom to decline sometimes. Both should have moments of running after the other, not only sexually but emotionally and spiritually as well.

So, in the face of crass language about sex in our culture, what might happen if we responded with healthy alternatives? Weddings in the Orthodox Church include a practice that can ignite our imagination for healthy public language and ceremony about intimacy. In marriage ceremonies, the bride and the groom are crowned in a rite that is not about declaring a king or queen in order to exercise authority over another. Instead, the crowns proclaim a marriage that is the beginning of a little kingdom that can be like the true, grand kingdom. In their unity and love for one another, the partners covenant with God to proclaim the love of God’s kingdom through each other. The crowns the spouses wear remind them to identify with a crown of thorns, choosing a marriage that constantly crucifies its own selfishness in order to grow in intimate unity and oneness with God and each other.

The Orthodox practice and the relationship we encounter in the Song of Songs remind us as Paul did: It’s a mystery, but when we talk about marriage, we are talking about Christ and the church. Marriage based on the Kingdom view of power, holistic intimacy based on the Kingdom view of power is, well . . . powerful.

May this be our sexual witness.

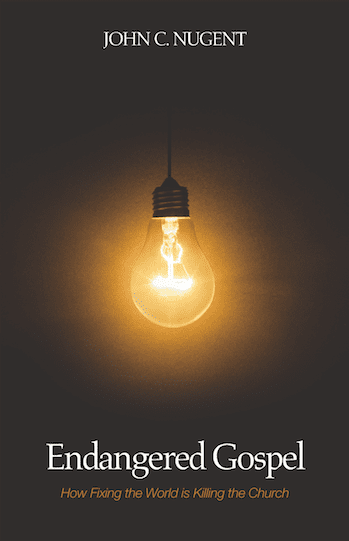

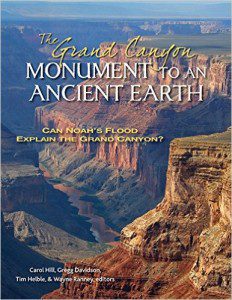

Does it matter? It is important that Christians, and especially church leaders and teachers, realize that the evidence for an ancient earth is impressive and persuasive. In the final chapter the authors (and the chapter is attributed to all of them) address the claim that the difference between the Young Earth flood geology view and the conventional old earth view is “because of the biblical or humanistic “glasses” each person wears.” (p. 207) Both are doing good “science” but conclusions are driven by worldview. But this isn’t true. Most of the authors of this book are strong Christians who take the Bible very seriously. I have had the opportunity to meet and talk with a number of them (Gregg Davidson, Joel Duff, Stephen Moshier, Ralph Stearley, and Ken Wolgemuth). These men are not lukewarm Christians dedicated to a humanistic approach to life or the world around us.

Does it matter? It is important that Christians, and especially church leaders and teachers, realize that the evidence for an ancient earth is impressive and persuasive. In the final chapter the authors (and the chapter is attributed to all of them) address the claim that the difference between the Young Earth flood geology view and the conventional old earth view is “because of the biblical or humanistic “glasses” each person wears.” (p. 207) Both are doing good “science” but conclusions are driven by worldview. But this isn’t true. Most of the authors of this book are strong Christians who take the Bible very seriously. I have had the opportunity to meet and talk with a number of them (Gregg Davidson, Joel Duff, Stephen Moshier, Ralph Stearley, and Ken Wolgemuth). These men are not lukewarm Christians dedicated to a humanistic approach to life or the world around us.

Standing on the shoulders of giants. Reeves and Donaldson also dig into the importance of community in science. Reeves and Donaldson point out that productivity in the sciences is always a community endeavor. New ideas and insights seldom, if ever, arise in isolation. Solo papers are relatively rare. Many projects require dozens of participants. Any idea or result, even those that may come from an individual, must be defended to the full community.

Standing on the shoulders of giants. Reeves and Donaldson also dig into the importance of community in science. Reeves and Donaldson point out that productivity in the sciences is always a community endeavor. New ideas and insights seldom, if ever, arise in isolation. Solo papers are relatively rare. Many projects require dozens of participants. Any idea or result, even those that may come from an individual, must be defended to the full community. Cultivate Humility. The last chapter of this section The Known Unknowns is worth digging into in more depth. This section isn’t (or shouldn’t be) directed solely at scientists. Scholars of all sorts, including theologians and pastors or any Christian teacher, would benefit. This post led off with a text from James on humility. Many other passages come to mind as well.

Cultivate Humility. The last chapter of this section The Known Unknowns is worth digging into in more depth. This section isn’t (or shouldn’t be) directed solely at scientists. Scholars of all sorts, including theologians and pastors or any Christian teacher, would benefit. This post led off with a text from James on humility. Many other passages come to mind as well.

With the SBC convention this summer came a series of stories …

With the SBC convention this summer came a series of stories …