A scientific theory is not a hunch or mere speculation. Rather the term refers to a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by many congruent lines of data. A further explanation from the NAS web site is helpful.

A scientific theory is not a hunch or mere speculation. Rather the term refers to a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by many congruent lines of data. A further explanation from the NAS web site is helpful.

Many scientific theories are so well-established that no new evidence is likely to alter them substantially. For example, no new evidence will demonstrate that the Earth does not orbit around the sun (heliocentric theory), or that living things are not made of cells (cell theory), that matter is not composed of atoms, or that the surface of the Earth is not divided into solid plates that have moved over geological timescales (the theory of plate tectonics). Like these other foundational scientific theories, the theory of evolution is supported by so many observations and confirming experiments that scientists are confident that the basic components of the theory will not be overturned by new evidence. However, like all scientific theories, the theory of evolution is subject to continuing refinement as new areas of science emerge or as new technologies enable observations and experiments that were not possible previously.

Robert Asher, in Evolution and Belief, runs through some of the evidence for evolution. Early classifications of animals were based on comparative anatomy and embryology. The first attempts to derive a “tree of life,” a broad scale theory of genealogical relationships relied heavily on this data. After 150 years of scientific investigation we now also possess a much more complete fossil record and have access to extensive data from molecular biology and the genome project. All of these lines of evidence (comparative anatomy, embryology, fossil record, and molecular biology) confirm the same basic theory of interrelationships.

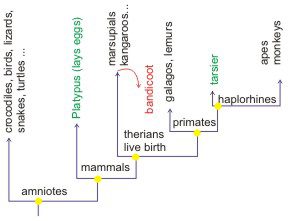

Stratigraphy. The geological column, strata of fossil bearing rocks, provides one strong thread of evidence for evolutionary progression. The layers that contain the fantastic variety of trilobites, as in the image above, fall between ca. 520 and 250 MYA (million years ago). This image is of a section of a large slab from 450 MYA in the Oxford University Museum of Natural history. In contrast the earliest mammals don’t show up until layers that date to 215 MYA or primates until 56 MYA. The timeline to the right highlights part of Fig. 4.1 p. 64 (click on it for a larger version). Much more information is available in the full figure. Finding a variation of trilobite alive today, or a even tyrannosaurus, wouldn’t be a problem for evolutionary theory. Finding a rabbit or a monkey in a Cambrian layer (541-485 MYA) or an Ordovician layer (485-444 MYA) would undermine the entire picture and send us back to the drawing board… on par with discovering something that moves through space faster than the speed of light.

Stratigraphy. The geological column, strata of fossil bearing rocks, provides one strong thread of evidence for evolutionary progression. The layers that contain the fantastic variety of trilobites, as in the image above, fall between ca. 520 and 250 MYA (million years ago). This image is of a section of a large slab from 450 MYA in the Oxford University Museum of Natural history. In contrast the earliest mammals don’t show up until layers that date to 215 MYA or primates until 56 MYA. The timeline to the right highlights part of Fig. 4.1 p. 64 (click on it for a larger version). Much more information is available in the full figure. Finding a variation of trilobite alive today, or a even tyrannosaurus, wouldn’t be a problem for evolutionary theory. Finding a rabbit or a monkey in a Cambrian layer (541-485 MYA) or an Ordovician layer (485-444 MYA) would undermine the entire picture and send us back to the drawing board… on par with discovering something that moves through space faster than the speed of light.

That last is an interesting example. An experiment a few years ago to measure the speed of a neutrino (tiny neutral particles with a mass less than a millionth that of an electron) appeared to give a result faster than the speed of light (here). There was a great deal of skepticism, but the response of the community was to dig deeper, to substantiate the result or determine where the error was made. It was a subtle error in the instrumentation – but dogma didn’t rule the day, data did.

Large scale revolutions are rare, but fine scale refinements are constantly being made, in evolutionary biology and in other sciences. This is normal progress. The timeline picture above presents a good overview, but it is always subject to refinement. The appearance of tetrapods is a good example.

At a finer scale, the story is of course more complex. Paleontologists are generally not under the illusion that we’re out to identify literal distinct ancestors of modern groups. Nor do modern paleontologists claim that geologically older fossils always represent ancestral organisms. In fact, many fierce debates exist about the extent to which the fossil record accurately reports the first appearance of a given group, and paleontologists realize that the first appearance in the rock record is an underestimate of the actual first appearance of a species on our planet.

Indeed, a sure-fire way of making a splash in paleontology is to push back the record of a group by finding the oldest [insert favorite animal here]. Such discoveries happen quite frequently, for example, the recent description of a trackway of a land-walking vertebrate from rocks in southeastern Poland that date to the middle Devonian, about 397 million years ago. These prints show that some animals at that time were capable of propelling themselves with muscular limbs that ended in digits. They predate the oldest skeletal remains of animals with muscular limbs and digits (e.g., Tiktaalik, perhaps better known as “fishapod”) by about 18 million years, and they predate other trackways by about 12 million years, or perhaps even less, given the uncertainty on the age of the other trackway sites. Relative to what had been thought to be a 385 million-year fossil history of tetrapods, the Polish discovery extends the record of this group by about 3%. This is an important find, but does not change at all the fact that as shown in Figure 4.1, the first appearance of major groups correspond quite closely with the genealogical relationships inferred from anatomical and molecular evidence. (p. 70)

I’ve posted on Tiktaalik roseae a couple of time before. The most relevant to this discussion is Tiktaalik roseae revisited.

Punctuation. Asher also points out that the fossil record doesn’t show a slow, gradual set of transitions. There are a number of reasons for this. Catastrophic events like meteor strikes can have a major influence on the environment. Another possible reason is the range of biological space accessible. Unicellular organisms can’t do all that much. Multi-cellular organisms can do much more – and once a multi-cellular organism appears populations can differentiate to occupy different spaces (“niches”) consuming, competing, or coexisting. Once a backbone is on the scene various organisms that use a backbone can develop. Features can evolve more than once (convergence) with organisms reaching the similar solutions from different directions, often constrained by basic chemistry and physics, but there are generally telltale signs beneath the surface (e.g. bone structures or DNA sequences) that help establish connections or the lack of connections.

Punctuation. Asher also points out that the fossil record doesn’t show a slow, gradual set of transitions. There are a number of reasons for this. Catastrophic events like meteor strikes can have a major influence on the environment. Another possible reason is the range of biological space accessible. Unicellular organisms can’t do all that much. Multi-cellular organisms can do much more – and once a multi-cellular organism appears populations can differentiate to occupy different spaces (“niches”) consuming, competing, or coexisting. Once a backbone is on the scene various organisms that use a backbone can develop. Features can evolve more than once (convergence) with organisms reaching the similar solutions from different directions, often constrained by basic chemistry and physics, but there are generally telltale signs beneath the surface (e.g. bone structures or DNA sequences) that help establish connections or the lack of connections.

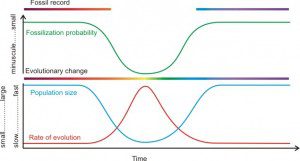

Another reason for “punctuated equilibrium” or the apparently abrupt appearance of new forms is more subtle. Evolutionary change is faster in a small population than in a large population and fossils are not generally left by small populations. This isn’t the only factor at play, but it is a significant one. Oftentimes evolution occurs by isolation of a small population from a larger group. This would cause a drop in the local population and the subpopulation wouldn’t reappear in the fossil record until it was different and had grown large enough to leave an appreciable fossil record.

Another reason for “punctuated equilibrium” or the apparently abrupt appearance of new forms is more subtle. Evolutionary change is faster in a small population than in a large population and fossils are not generally left by small populations. This isn’t the only factor at play, but it is a significant one. Oftentimes evolution occurs by isolation of a small population from a larger group. This would cause a drop in the local population and the subpopulation wouldn’t reappear in the fossil record until it was different and had grown large enough to leave an appreciable fossil record.

This is not to say that all speciation events are allopatric, i.e., that they result from the reproductive isolation of small founder populations. Nor does it mean that anything “intermediate” in morphology has no chance of becoming a fossil… However, it does lead to an understanding of how an important model of speciation should typically manifest itself in the fossil record: a given species should typically show stasis, or “equilibrium,” during those times when it is well adapted to its particular environment and sufficiently numerous to leave behind evidence of its existence in the fossil record. An isolated, small daughter population – one in which evolutionary change is prone to become widespread – will be less likely to leave behind fossil representatives simply because it is small. After many generations, and possibly eons of geological time, if and when that population becomes big enough to leave behind fossil representatives, the paleontological “equilibrium” of the parent species will be accompanied (and not necessarily replaced) by the apparently sudden appearance in the fossil record, or “punctuation,” of the daughter species. (p. 76-77)

There is more in this chapter. Asher discusses some of the problems with “quote-mining” in some of the anti-evolution literature (no one likes to be misquoted out of context). He also introduces the fascinating idea that evolution may work at the level of populations as well as individuals. It is often said that all evolution is microevolution acting on individuals, and it is the accumulation of small changes in that results in what we see as macroevolution. However, evolution at the population level may give results counter to those seen if only individuals are considered, a kind of macroevolution. This doesn’t change the general paradigm of evolution by natural selection, but it does impact the outcome of the process. Evolutionary biology is an active field because there much room for new work and future refinement. This is exciting to any scientist.

Do you think the fossil record is a problem for the theory of evolution?

What would you expect from a transitional form?

If you wish to contact me directly you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.