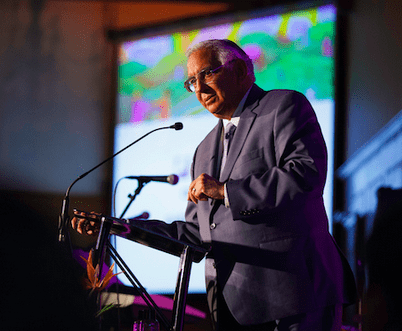

This post, by Jeff Cook, comes to me the day after preaching a sermon at Church of the Redeemer! I believe in sermons, but I do know that some churches create a Sunday service that functions as “Come hear me preach” event. When the whole of the Sunday “event” is wrapped up in that sermon then church becomes less than what church ought to be. Some criticize the sermon out of “sermon” envy — they are not as good as those around them who can draw in the crowds; some, however, have ideas that deserve consideration. Sermons today can be both over valued and under valued.

This post, by Jeff Cook, comes to me the day after preaching a sermon at Church of the Redeemer! I believe in sermons, but I do know that some churches create a Sunday service that functions as “Come hear me preach” event. When the whole of the Sunday “event” is wrapped up in that sermon then church becomes less than what church ought to be. Some criticize the sermon out of “sermon” envy — they are not as good as those around them who can draw in the crowds; some, however, have ideas that deserve consideration. Sermons today can be both over valued and under valued.

Why the Sermon is Toxic (Jeff Cook)

Okay, that’s a little a strong, but I would like to start a series reconsidering the role of teaching in the church service and argue that the sermon causes a host of problems and its benefits are not worth the cost.

The Sermon

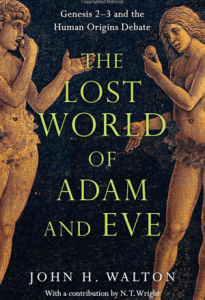

By “the sermon”, I do not mean a homily or discussion-propelled teaching. I do not mean the occasional address to paint priorities or guide the actions of a community. I mean the weekly 30-55 minute lecture on the Bible that sits at the center of most church gatherings.

The sermon is not secondary for most churches. The sermon determines what happens in the time we gather. Often the worship plan begins with the sermon topic and everything else adjusts.

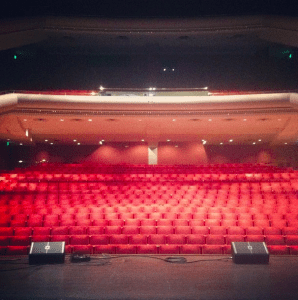

Sermons not only are the centerpiece of most gatherings, but the primary reason many of us come together. Our spaces are constructed to elevate the speaking platform. Few churches grow beyond a few hundred without exceptional teachers, and as such when money is spent to expand the church, the focus is seats and the pulpit. It seems the most expensive church buildings recently constructed are simply large auditoriums for superstar teachers to proclaim biblical truths with childcare available on the side. Young church leaders may look at “the success” of such peers and challenge themselves to up their game communicating to ensure that they too can create a growing church.

But is this healthy?

The Medium is Still the Message

First, because the medium is the message, it’s worth asking what the medium of the sermon communicates.

The sermon loves spectators. The sermon desires the crowd. The sermon requires very little in return from those assembled and perhaps that’s why we elevate it: you can remain anonymous at a church and still attend (by the way, here’s the collection plate). The sermon is not interested in dialogue. It is not interested in the most effective methods of teaching (lecture is always ranked near the bottom of successful styles of communication). The sermon is most interested in short term gain: inspiring the masses for the day.

As a medium, the sermon shows us that we think discipleship occurs best through listening to a local scholar. The sermon tells us the biblical opinion of the teacher is worthy of gathering weekly.

The medium of the sermon is how we evangelize and draw others into the community of Christians, and as such the medium says, “if you believe what is preached in the sermon only then will you be one of us.”

The medium of the sermon tells us how we think truth about God is disseminated. The sermon deemphasizes experience and elevates propositional knowledge.

And the sermon teaches us to sermonize when speaking to others about God. The sermon-medium teaches me that if I have the message of God for my culture (to my friends at work, to my family table, to those at the bar), I will sermonize when speaking about God—because that is how I’ve been taught. Dialogue through difficult theological matters is seldom elevated in the local church let alone the church gathering.

Worse still, the medium of the sermon reduces thinking. What the sermon does is create Christians who are increasingly ineffective at actually talking to people who disagree with them. Because the way we experience and process information about God is often custom fit to our pre-held beliefs, the sermon trains us–not to process and communicate–but to parrot and talk down to others. I submit this kind of approach to engaging those who disagree comes from the sermon: we are used to the person informed by God telling us what we need to do and believe and not having an opportunity to respond and if we actually love Godl, we are to step in line and obey.

As a philosopher, I’m constantly shocked not only by how poor the arguments coming out of Christian circles are about ethical, political and metaphysical issues, but that Christians communicate their opinions through decrees. “The Lord says” is seen as an effective argument–and the reason some think it effective is because they’ve been conditioned by the sermon.

The one thing I see both in my classes and in those coming to my church because they are done with other church communities—is people want freedom to talk, to be wrong, to work out their salvation with fear and trembling as God works within them. But sermon does not allow this.

Small Groups and Questions

At this point many will say, well we have space in our church for conversation; they are called small groups.

But notice how strange this answer is from those who have elevated the sermon: we are spending the vast majority of our collective time, collective resources and collective energy creating events in order to ensure that discipleship and engagement with the scriptures effectively occurs … somewhere else.

I imagine many of us, especially those who have not constructed a multi-million dollar facility with all eyes pointing toward the podium, are looking for good ideas to replace the sermon. In the next few weeks I will bring up a couple of other issues caused by an unhealthy elevation of the sermon, and prescribe a host of ways to rethink our liturgy.

For now however, I would love your push back and your ideas:

First, is the critique of the sermon worthy? Have we overemphasized the teaching portion of our gatherings to our detriment and how?

Second, how do you solve this problem? What replaces the sermon? What does your liturgy look like?

One last note, my own church has been wrestling with replacing the sermon for a year now. It doesn’t happen over night. Even for the thoroughly convinced is quite difficult. If you go down this road, as a practitioner or as someone encouraging a leader, it is tricky and requires small changes, lots of perseverance, prayer and creativity.

I look forward to dialoguing with you about these topics.

Jeff Cook is a pastor of Atlas Church in Greeley, Colorado and he is the author of Seven: The Deadly Sins and the Beatitudes(Zondervan 2008). You can connect with him at everythingnew.org and @jeffvcook.