Christianity is a religion founded on hope precisely because it is founded in God and his work in the world through Jesus, the Messiah of God. The resurrection is the clearest example of this hope, but it is far from the only example in scripture. John Polkinghorne outlines New Testament insights into Christian hope and the theological foundation of this hope in chapters seven and eight of his book The God of Hope and the End of the World.

Christianity is a religion founded on hope precisely because it is founded in God and his work in the world through Jesus, the Messiah of God. The resurrection is the clearest example of this hope, but it is far from the only example in scripture. John Polkinghorne outlines New Testament insights into Christian hope and the theological foundation of this hope in chapters seven and eight of his book The God of Hope and the End of the World.

First – relevant New Testament passages. Jesus leaves no doubt about the reality of the final resurrection or of the continued existence of the people of God. As an example, consider the reply to the Sadducees reported in Mark 12.

Now about the dead rising—have you not read in the Book of Moses, in the account of the burning bush, how God said to him, ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob’? He is not the God of the dead, but of the living. You are badly mistaken!”

This hope permeates Paul’s writing as well. From 1 Thessalonians, thought by most to be the earliest of the letters contained in the New Testament, to Romans, which (excepting the pastoral) is thought to be his last. His thinking developed over this time, from an expectation of imminent consummation to a realization that this would be a rather longer period of time, but his hope in resurrection never faltered. Polkinghorne summarizes from Romans:

The rest of the New Testament testifies to the belief that in the risen Christ the believer has been given a new and enduring life. ‘Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the father, so too we might walk in newness of life. For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.’ (Romans 6:4-5). Once again, it is trust in the faithfulness of God that is the ground of this hope. … It is the Spirit already at work within us who is the testimony to life beyond the grave. ‘If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Jesus from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also through his Spirit who dwells in you’ (Romans 8:11). Schwöbel comments that ‘it is the Spirit of God who bridges the eschatological tension between the already and not yet’. (p. 83-84)

Hope permeates as well the Gospel of John, the letters of John and Peter, and Revelation. The tension between already and not yet is, Polkinghorne says a little further on, “an intrinsic component of our eschatological thinking.” (p. 89) Throughout the New Testament Jesus is both the One who has come and the One who is to come.

Next – Theological Foundations of Hope. Polkinghorne quotes Jürgen Moltmann: ‘From first to last, and not merely in the epilogue, Christianity is eschatology, is hope, forward looking and forward moving, and therefore also revolutionary and transforming the present.’ (p. 93 quoting from Moltmann’s Theology of Hope) Hope is invested in the future, but it is not a cheap hope that fails to take note of the reality of the ups and downs of history. Atrocities persist, past, present, and presumably future. What is the ground of true hope?

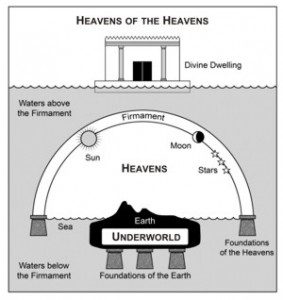

There is only one possible source: the eternal faithfulness of the God who is Creator and Redeemer of history. Here Christianity relies heavily on its Jewish roots. It is only God who can bring new life and raise the dead, whose Spirit breathes life into dry bones and makes them live (Ezekiel 37:9-10). Hope lies in divine chesed, God’s steadfast love. (p. 95)

An impersonal creator or divine cause is insufficient to the task.

To sustain true hope it must be possible to speak of a God who is powerful and active, not simply holding creation in being, but also interacting with its history, the one who ‘gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist’ (Romans 4:17). This same God must be the one whose loving concern for individual creatures is such that the divine power will be brought into play to bring about these creatures’ everlasting good. The God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ is just such a God. (p. 95)

Forgiveness is a part of our hope for the future, a forgiveness that is true today and leads to the future. But this is a forgiveness in which we must participate. The receiving and giving of forgiveness are linked and mutually necessary. Matthew 6:14-15, Matthew 18:35, and James 2:13 cannot be brushed aside.

The reality of resurrection in the New Testament is theologically necessary for Christian hope. Progressive Christian views that relegate Christian hope to “the attainment of a life lived with God now and not in some future state of blessedness beyond death” are insufficient to the task. Such a view is void of any genuine hope for one whose life is cut tragically short by accident, violence, or disease. It is devoid of genuine hope for the one who suffers even to death for the gospel of Christ. Yes we should work today to right the wrongs of the world. But this is not ultimately where our hope lies. Polkinghorne sums up: “We shall all die with unfinished business and incompleteness in our lives. There must be more to hope for.” (p. 99)

Christian hope is in a physical and individual resurrection. We will not be preserved simply in the eternal memory of God, a view I first came across in John Haught’s book Making Sense of Evolution. Polkinghorne responds to this idea noting that a memory is a static thing and thus devoid of any real hope because it removes the reality of the individual and of redemption from the picture. In contrast: “actual eschatological fulfillment demands for each of us a completion that can be attained only if we have a continuing and developing personal relationship with God post mortem.” (p. 100) A true hope must include future development and growth.

Finally, we embrace the true hope for future in the sacraments of baptism, buried and raised with Christ (Romans 6), and the bread and wine … ‘For whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.’ (1 Cor. 11:26) We embrace in the true hope for the future the conviction that nothing good will be lost and that our strivings today will bear everlasting fruit.

God is the God of hope because God is the God of the past, present and future. The risen Christ is the one who is ‘the first and the last, and the living one. I was dead, and I see, I am alive for ever, and I have the keys of Death and Death’s Domain’ (Revelation 1:17-18). Those who embrace hope place themselves in the hands of the Lord of the open future. To do so is an act of total commitment to the One who is faithful. (p. 101-102)

A worthy meditation leading into Palm Sunday, Holy Week and Easter.

Is Christianity a religion founded on hope?

How should this hope inform our actions today?

If you wish to contact me, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net.

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.