Morpheus Ravenna’s last blog post Theurgic binding: or, S#!t just got real has generated a lot of discussion. I had a very personal response to it. Morpheus edited her post to include links to several others and added a follow-up of her own. They make for interesting reading even if you don’t agree with all of them.

These essays discuss the risks and benefits of working with and for the Gods. And behind all this divine risk assessment are some ideas and assumptions about the Gods: who are They? What are They? What do They want from us?

There’s a term for these questions about the Gods and our attempts to answer them, a term that rarely gets used in Pagan circles: theology.

The English word theology comes from the Greek theos (God) and logy or ology (study of). Theology is the study of the Gods. For over 1400 years, theology in the West has been only the study of the Abrahamic God. So while pagans invented theology (several times, in different places) and some of it has survived to modern times, modern Paganism does not have a full body of robust ideas about the Gods.

From the Romantics singing of Pan to Gardner’s witchcraft to Starhawk’s ecofeminism, modern Paganism has been light on thinking and heavy on doing. This has mostly been a good thing. One of the attractions of Paganism is that it’s an experiential religion – it’s a religion of doing, not a religion of hearing. “Sing, feast, dance, make music and love.” Pour libations to the Gods. Whether you think They’re beings or aspects or archetypes or personifications is less important than the fact you’re pouring libations to Them. Right action is more important than right belief.

For many people this is enough. They want to live good lives and do the right things, but they have their hands full with other aspects of life. Save them a place around the bonfire and let them know when the next roadside trash pickup is and they’re happy.

But for those of us who are called to the Gods, or who the Gods have claimed, it’s not enough.

How do we know anything about the Gods? We have the stories our ancestors told about them. We have the work of mainstream historians, archeologists, and anthropologists. We have the experience of contemporary Pagans and polytheists. And we have our own experiences of Them.

There are two problems with theology. The first is thinking we can know everything about the Gods, or at least everything worth knowing. And if we know everything then anyone who disagrees with us is obviously wrong. The last 1400 years has shown us what that brings. Even if we aren’t inclined to oppress those who think differently, if we think we already know everything we aren’t likely to listen to someone who has different ideas that may be informative and helpful. My way is not the only way.

The other problem is thinking we can know nothing. Yes, the Gods are vast and complex and mysterious. No, we can never have the certainty about Them we have about things that can be objectively measured and analyzed. But we can know some things. More importantly, when we think we can know nothing about the Gods we aren’t likely to listen to someone who has different ideas that may be informative and helpful. All ways are not equally true.

Two very different problems, two very similar results.

Good theology looks at all the information about the Gods – all the lore, all the history, all the experience – and draws reasonable inferences about who and what They are and how we can best interact with Them.

Good theology is an incremental process. Once a theologian is confident about one concept, she can use it as a foundation for further concepts.

Good theology is consistent. Humans tend to overrate consistency (we prefer mediocre certainty over uncertainty that may be excellent or may be horrible), but intellectual consistency is critical for building good theology. Once you accept certain foundational assumptions, other beliefs are closed to you because they are inconsistent.

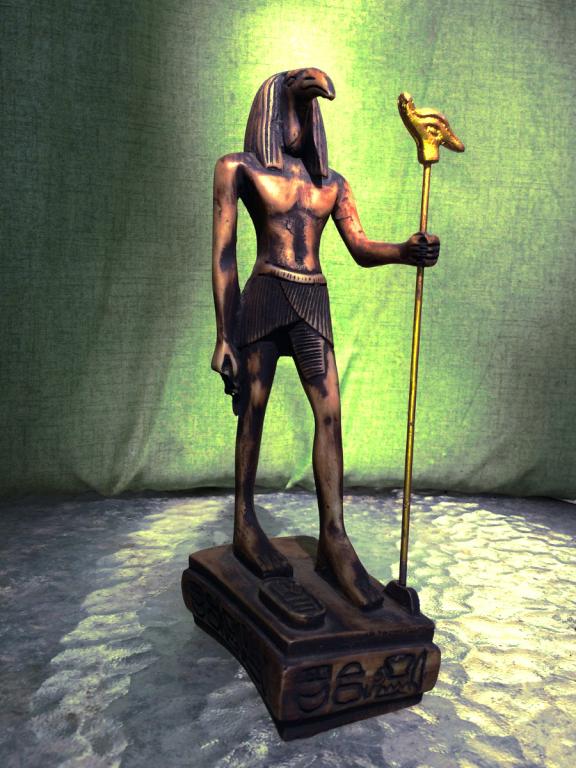

This brings us back to the reactions to Morpheus’ essay. Two of the basic premises of contemporary devotional polytheism are that the Gods are many and that They have agency. They are individual beings with Their own areas of responsibility and interest, Their own goals and desires, and Their own personalities.

These premises are so basic and so foundational that many polytheists have chosen to segregate themselves from others in the Big Tent of Paganism rather than constantly argue with those who insist the Gods can only be understood in psychological or metaphorical terms.

If you believe the Gods are many and have agency then you cannot also believe They can’t affect you unless you permit it. The two propositions are logically inconsistent.

Humans are many and have agency and they most definitely can affect you without your permission – just ask any mugging victim. Are the Gods less than humans? Isn’t “more than human” another of the foundational assumptions about the Gods?

In the absence of robust polytheology and proven polytheological methods, it is easy for unhelpful ideas to slip into our thinking about the Gods. We’re pretty vigilant about watching out for Abrahamic ideas, but ideas from popular religion and popular culture are often hard to catch – particularly if they’re comforting.

The Gods all love us and are here to help us grow? The Gods would never use us for Their own ends? We have so much control over our lives even the Gods can’t impact us unless we let Them? Not all of these ideas were expressed in the discussion around the Theurgic Binding post, but I’ve heard them all recently in one place or another. They may make some people feel good, but they don’t represent good thinking about the Gods.

Developing good theology is not about establishing orthodoxy. Paganism and polytheism are and will remain religions that value right action over right belief. Experiencing the Gods is more important than the intellectual concepts used to interpret those experiences.

Good theology helps us to better understand who and what the Gods are so we can better work with and for Them. It helps us place our experiences in a wider context and in a greater narrative. It enables like-minded people to build on each other’s work and grow our overall body of understanding. And perhaps most importantly, it helps us build deeper devotional practices and more effective service to the Gods and to our communities.

This is part of our work here on the Pagan internet: thinking about the Gods, critiquing ideas, and trying them out to see to what works and what doesn’t – what’s helpful and what’s not. Here and elsewhere we’re slowly building a new Pagan theology.